- Visitor:8

- Published on: 2024-10-16 04:21 pm

The Story, Symbol, and Significance of Skandamātā

sdas

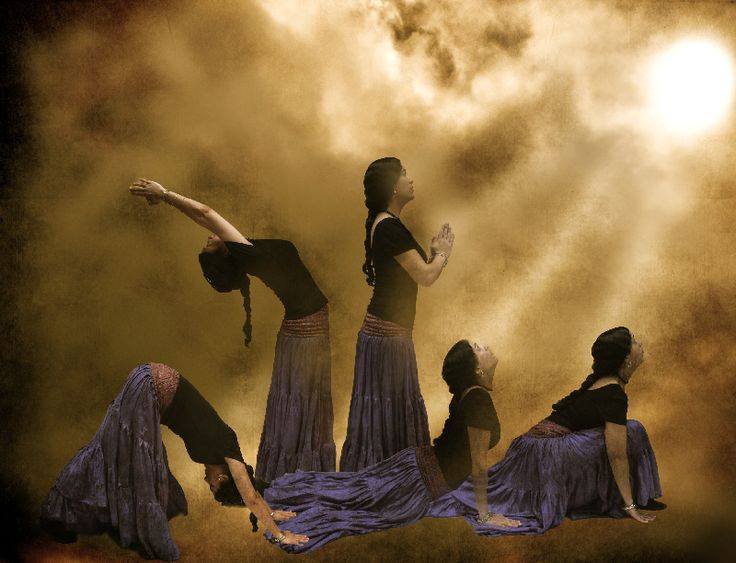

Of Water and the Spirit: Ritual, Magic, and Initiation in the Life of an African Shaman

… for men being all the Workmanship of one omnipotent and infinitely wise Maker; all the servants of one Sovereign Master, sent in to the world by his order and about his business, they are his property, whose workmanship they are, made to last during his, not one another’s pleasure …

Locke’s belief that human beings belong to God precludes any right to abortion or to suicide. In his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (Book 1, Chapter 3, Section 19), where he described abortion as one of the most immoral acts, Locke argued that human beings have an immortal soul that belongs to its Creator. The lives of human beings are not theirs to begin or end.

Against this view, Hobbes asserted that women have dominion over their bodies and therefore over their offspring. In De Cive, Chapter 9, he wrote:

… Amazons have in former times waged war against their adversaries, and disposed of their children of their own wills, and at this day in diverse places, women are invested with the principal authority … the child is therefore his whose the mother will have it, and therefore hers; wherefore original dominion over children belongs to the Mother …

Hobbesian logic does not require accepting any particular view of abortion, even Hobbes’s. The goal is not agreement, but modus vivendi. A legal framework governing abortion can only be reached by a political settlement, periodically renegotiated. The same applies to issues around assisted dying, sexuality and gender. When society is divided on such questions, the attempt to resolve them by inventing and enforcing rights is fatal to peace.

- 4 min read

- 0

- 0