- Visitor:561

- Published on: 2025-03-06 02:16 pm

Indic Social Sciences, An Urgent Need: A Book Review of ‘A Dharmic Social History of India’ (Part II)

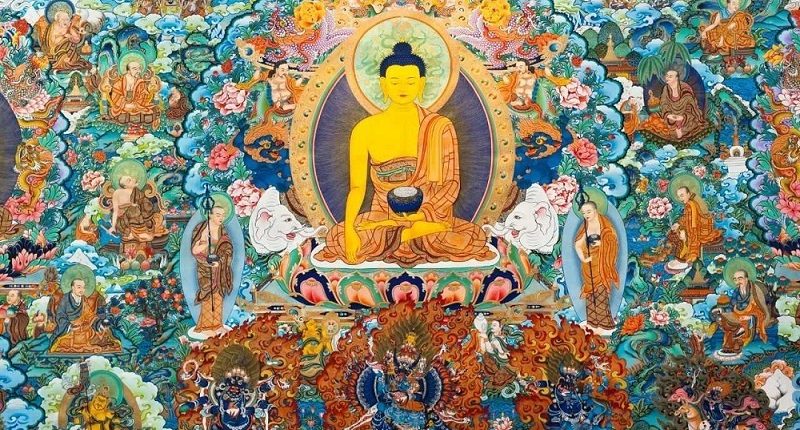

In the medieval times, Saint Jñāneśvara asking buffalo to recite the Vaidika Mantras, elucidating the principle of oneness of reality and humbling ignorant sections of society; Saint Nāmadeva lamenting his low birth, making Viṭṭhala to turn round temple wherever he turns; Saint Cokhāmela, from Māhār community, invoking the analogy of Goddess Gaṅgā and Mother Earth as the purifier of all, without any discrimination to remove any feeling of superiority among many; also social elevation of the whole Māhār community through valor and devotion; Saint Caṇḍīdāsa’s love for Rāmī, a washerwoman, turning into spiritual quest and breaking all taboos related to gender discrimination; Caitanya Mahāprabhu’s resuscitation of pastoral tune as divine music, his wandering among all sections of society to share the holy name of God and assimilation of outcaste Buddhist bhikṣus and bhikṣunīs (Neras and Neris) into the fold of Vaiṣṇava tradition. These heart-touching stories of social harmony and inclusion, grounded in the Vaidika tradition, are brilliant examples of social justice in India, much prior to any ‘progressive’ ideas from the West. They were purely indigenous attempts of reforming society from within; where ‘bhakti saints define dharma more than the śāstras’. These social reforms would have continued, if colonial ideas had not distorted our sense of social dynamism.

In

the first part of the review (click here to read), we have gone through various

social myths that have been promoted by alienated intelligentsia as ‘the

standard model’ of Indian social history and its thorough rebuttal in this

book. After deconstruction of these false narratives, we touched upon the

central theme of social dynamism in India– the archetype of yajña and bhakti

movement - as the guiding civilizational forces that have shaped Indian social

history over millennia. It has pertinently led us to few important

queries:

(a) If India’s history is not studded with ‘social revolutions’

and the disruptive model of the West, how did it deal with social stagnations

and changes?

(b) If not through violent upheavals and massacres, how Indians

have accommodated necessary changes in the social structure?

Or

the larger question is: Is there any Indic social model that can help us

understand the social dynamism in India, particularly that manages social

inclusion and harmony in society?

The

Self-realized Souls: The Silent Reformers

Aravindan

emphasizes the prominent role of the self-realized souls, as the living

embodiment of Indic spiritual tradition, shaping Indian social landscape

through their subtle presence; transcending devotees of any rigid social

construction. The spiritual transformation of an individual, in the presence of

such great saints, naturally deconstructed their social biases and inhibitions.

The author claims:

“Thus,

bhakti becomes the most potent link of creativity and justice between the

society and the individual. It simultaneously affects the individual realization

of inner potentials in a creative and transcendentally expansive nature while

at the same time challenging the societal status quo, injecting vitality into

social emancipation.” (170)

What

most of the colonial Indologists and their perverted successors have missed in

the Indian social landscape is the presence of these saints in influencing the

Indian mind. Their obsession with ‘Brahmins’ and rigid social stratifications

have led them to only four-fold classifications of society; neglecting the role

of the subtle ‘fifth fold’ existing beyond any social category, though exerting

the most powerful influence on Indian Social History. Sri Aurobindo also

emphasizes:

“[T]he

man of a higher spiritual experience and knowledge, born in any of the classes,

but exercising an authority by his spiritual personality over all, revered and

consulted by the king of whom he was sometimes the religious preceptor and in

the then fluid state of social evolution able alone to exercise an important

role in evolving new basic ideas and affecting direct and immediate changes of

the socio-religious ideas and customs of the people.” (676)

In

the presence of these spiritual giants, society gets infused with renewed vigor

and spirit, elevating people and broadened their dominant conceptions. Some of

these conceptions are wonderfully decoded through various examples.

The

Feet of the Puruṣa& Other Misconceptions

The

stigmatizing association of the feet and crematorium ground with untouchables

and other lower castes are few such conceptions, unfolded in the proper

historical context. The origin of lower jātis from the feet of the Puruṣa

has been narrated as the source of discrimination, neglecting the elevation of

the feet as the holiest and sacred part of spiritual tradition in India. The

most revered ācāryas in India have used the title ‘Bhagavat-pāda’,

taking pride in getting associated with the feet of the divine, removing any

stigmatization associated with it. The author has also provided examples from

the Kṣatriya community taking immense pride in calling themselves ‘a servant of

the feet of Bhagavan’. Aravindan explains:

“The

motif of Śūdra and River Gaṅgā coming from the sacred feet of Viṣṇu has been a

consistent means across the centuries to glorify the Śūdra origin of a ruler

and seamlessly transform them into Kṣatriyas.” (256)

Again

this must not be construed through western framework of social revolution. On

the contrary, it was an organic and natural outcome of spiritual

transformation. The author aptly reminds us, while narrating incidence of one

of the Azhwar saints:

“Mathurakaviāzhwār,

a Brahmin pandit well-versed in Vedas, was considered the counterpart to

Nammāzhwār’s feet. This was not a conscious social engineering effort, as it

would be seen today. Instead, this was a spontaneous expression of bhakti

solidifying into a narrative well-anchored in the Vedic vision of

non-discriminatory non-dualism, inherently challenging social stratification

and exclusion without even making that its primary objective. Yet its impact is

more powerful, pervasive, holistic, and sustaining through centuries than any

conscious ‘social revolution’.” (223)

If

connotations of the feet get elevated as the holiest of holy, then association

of untouchables as ‘walking crematoriums’ was transformed as the most sacred

place of Śiva where he ‘stands and dances’, wonderfully illustrated through the

story of PeyAmmai, a spiritual giant considered as the ‘Mother of Śiva’.

Nothing becomes purer than crematorium ground where everyone merges in divine,

also elevating all kinds of menial tasks associated with cremation.

The

Yajña Model & Social Occupations

It

also proves that Hindu Dharma excludes none. It keeps on expanding its sphere

of compassion and empathy for everyone – however inferior jāti or

associated tasks that may appear through a worldly lens. In fact, this

equanimity also paved the way for uplifting all communities and making them co-creator

in social and cosmic yajña. The seemingly menial task of fishing becomes

‘the Yajña of Fishing’, explained through the story of ThirugnanaSambanthar and

AthibhathaNayanar, who in their own ways, removed stigmatization of this

occupation because of ‘certain ethical excesses’ and ‘strict adherence to

non-violence’ of Jains and Buddhists. The author aptly narrates this:

“When

Athibhathar threw the fish into the sea, he showed that his work should be seen

as a ŚivaYajña. This occupation and hereditary guild, once labelled as defiled

and subjected to economic hardships, is now projected as an honourable

occupation and a holy Yajña.” (203)

The

similar examples with respect to other communities can be multiplied, where

defilement of certain occupations led to the social stagnation of a particular

community, eventually overcome with the strong foundation of Hindu Dharma. The

community of musicians and dancers, once looked down through the lens of

‘world-negating religions’ were uplifted with cosmic vision of oneness, again

illustrated through the brilliant life stories of Thiru NilakandaYazhpanar and

Thiru Nilanakkar where singing got associated as the divine profession, always

found place in the sacred traditions of temples and even homes of ‘orthodox’

Brahmins.

It

is these powerful living examples, embedded in the folk memory, that act as the

catalyst for social reforms, silently unfolding in all parts of India:

“This

represented a social revolution unprecedented in any part of the

then-contemporary world. Despite this, it was not even recognized as a social

revolution. The significance of a couple from a socially excluded community

sleeping in the most sacred space of the ritual and being acknowledged by the

Yajña flame had never been seen or acknowledged before.” (206)

Social

Emancipation: A Shaivite and Vaishnavite Traditions

A

benign act of compassion, arising as a spontaneous spiritual transformation,

has been the source of social dynamism in India. It is also reflected, and

quite well-known, in the legendary lives of saints from all walks of life.

Aravindan provides an apt example of PeriyaPuranam, a 12th

century Tamil work, compiling the lives of sixty-three Nāyanmārs:

“Among

the sixty three Nāyanmārs, thirteen belonged to the agricultural clan, two to

the cowherd clan, twelve to Brähmanās, twelve to the warriors and rulers, four

to AdiŚaiva, one to the Vaidhya Māmatrar, one to the potter, one to the

landless labourer-quasi serf, six to the trading community, one to the weaver,

one to the hunter, one to the fisherman, and one to the washerman.

Additionally, three of the sixty-three Nāyanmārs are women, effectively

covering the entire spectrum of the society in the literature.” (208)

All

these examples prove the axiom of Śaiva

community where ‘Dikṣā is given with no discrimination’, leading to spiritual

elevation of all, embracing everyone. On the other hand, the Vaiṣṇava

community, rooted in the stories of Viṣṇu, Rāma and Kṛṣṇa, also overcome social

stagnations through powerful bhakti tradition. It has been grounded in

the Śrīmad Bhāgavata Mahāpurāṇa, acting as ‘the spiritual mitochondria

of social emancipation’. The book abounds with fascinating stories of

saints who challenged the traditional social order: (1) Thirumazhisai Azhwar,

hailing from the community of bamboo basket weavers, asking Viṣṇu to leave the

city, when the king asked him for the same. In another incident, when

Brāhmaṇas, who stopped reciting the Vedas owing to his low caste as he

went and sat along with them, could not remember the Vedas and resumed

it only after his approval. (2) Nampatuvan, coming from a Panar community,

liberated Brahma Rākṣasa, who was Brāhmaṇa in his previous birth.

In

this context, the role of Śrī Rāmānujais

quite significant, who made ten ‘attributional and analogical distinction’

between orthodox Brāhmaṇas and non-Brāhmaṇa Vaiṣṇavas, elevating the later to

the highest pedestal, as they are devoid of arrogance and always immersed in

bhakti. Aravindan highlights the contribution of ŚrīRāmānujain

the following words:

“Thus,

ŚrīRāmānuja should be considered possibly the greatest spiritual emancipator of

his time. He initiated a silent but perhaps the most sustained revolution in

social emancipation. No other revolution in social emancipation has empowered

so many communities over millennia with little to no violence, even in the

midst of challenging circumstances such as alien invasions, forceful

proselytization, colonial wealth drainage, and imperial subjugation of people.

He was able to achieve this without the support of any empire or colonial

surplus.” (240)

This

is not to denigrate the Brāhmaṇa community, in particular, but to emphasize the

primacy of qualities over birth entitlements. At other place, the author

mentions the role of Brāhmaṇas in defending the barbaric onslaughts on temples,

during medieval times:

“However,

historical evidence shows that Brahmins were targeted, and, like other Hindu

communities, they were among the main targets in non-Hindu invasions. In these

situations, they chose to stand their ground and even accepted death

deliberately for the deities they worshipped. This demonstrates that Brahmin

rituals involved the adoration of and daily care of the deities rather than

Brahmin acting as intermediaries between the devotees and the gods. They were

the caretakers of the deities, which is a concept qualitatively different from

the idea of ‘priestcraft’.” (243)

It

seems that Indian spiritual tradition kept churning out, in every epoch, the

great souls who questioned the social stagnation for uplifting all sections of

society, removing any prejudices and discriminations. This continued even

during mediaeval times, as seen through various examples. An undercurrent of

spiritual yearning, also leading to social emancipation, is the only change

that was constant. We can take any historical epoch of India, zoom out events

and incidences, there is absolute certainty to find examples of such social

emancipations.

Social

Reformers in Medieval India

In

the medieval times, Saint Jñāneśvara asking buffalo to recite the Vaidika

Mantras, elucidating the principle of oneness of reality and humbling ignorant

sections of society; Saint Nāmadeva lamenting his low birth, making Viṭṭhala to

turn round temple wherever he turns; Saint Cokhāmela, from Māhār community, invoking

the analogy of Goddess Gaṅgā and Mother Earth as the purifier of all, without

any discrimination to remove any feeling of superiority among many; also social

elevation of the whole Māhār community through valor and devotion; Saint

Caṇḍīdāsa’s love for Rāmī, a washerwoman, turning into spiritual quest and

breaking all taboos related to gender discrimination; Caitanya Mahāprabhu’s

resuscitation of pastoral tune as divine music, his wandering among all

sections of society to share the holy name of God and assimilation of outcaste

Buddhist bhikṣus and bhikṣunīs (Neras and Neris) into the fold of Vaiṣṇava

tradition.

These

heart-touching stories of social harmony and inclusion, grounded in the Vaidika

tradition, are brilliant examples of social justice in India, much prior to any

‘progressive’ ideas from the West. They were purely indigenous attempts of

reforming society from within; where ‘bhakti saints define dharma

more than the śāstras’. These social reforms would have continued,

if colonial ideas had not distorted our sense of social dynamism. Aravindan

aptly pointed out:

“Here,

we see both the effect of the Bhakti movement and the continuing struggles of

social emancipation that the movement continues to confront. It was an organic

movement for liberation. It is likely that without colonial interference, the

‘outcastes’ could have evolved into a warrior community and eventually secured

their rights to enter temples. However, colonialism and modernization changed

the situation drastically. The bhakti inspired social emancipation had to

operate in a completely changed social milieu with pressing new challenges.”

(269)

The

Impact of Colonization on Social Harmony

The

colonization of India also had another pernicious impact on social harmony,

arising from the oppressive tax regimes and de-industrialization of then

flourishing small and medium scale industry. The sustainable architect of

self-reliant villages - reciprocal distribution, organic division of labor,

judicious use of local resources, decentralized guild management–all of themwere

adversely impacted, leading to social chaos. Historically, such colonial

policies led to various sorts of social conflicts, politically empowering one

community over another, creating animosity amongst them. This is one of the

foremost reasons for social stagnations in India, an area that has not been

properly studied in Indian academia. Aravindan shares the pertinent observation

of Iyya Vaikuntar:

“Poisonous

demonic (Western) low-natured ones who had been destroying the worlds all

around, also destroyed the Dharma of the noble Chānṟōr and transgressed against

them. He destroyed their works of charity…. Turning the communities against

each other, he destroyed the boundaries of cordiality of the Jāthis.” (344)

The

author also shares a poignant observation by Mike Davis, an author of ‘Late

Victorian Holocausts’, in this regard:

“Within

half a century of the British conquest the village communities were divested of

their cohesion and vitality, and they were fragmented into discrete, indeed,

antagonistic social groups which had formerly enjoyed an intimate relationship

of interdependence.….British policies, however Smithian in intention, were

usually Hobbesian in practice. In the case of Gujarat … the new property forms

freed village caste-elites from traditional reciprocities and encouraged them

to exploit irrigation resources to their selfish advantage” (354)

Iyya

Vaikuntar, a charismatic social reformer from Travancore, offered a profound pūrvapakṣa

of colonialism in India, rooted in Indic worldview, in fact ‘couched in Puranic

language’ and therefore making it accessible to the masses. The way the author

has narrated his important contribution in indigenous social reforms makes any

Indic seeker go over it again and again. It gives us the glimpse of what it means

to bring social reforms in India, touching the heart of every section of

society; transforming them from within, without shedding any blood. The author

sums up his contribution:

“This

movement could be considered one of the earliest, entirely Indic deep criticism

of colonial operations and their social manipulations. It differentiated Indic

social emancipation from the manipulative colonial ‘reforms’ which

superficially appeared to liberate people. Actually, it helped to consolidate

colonialism by psychological acceptance of the civilizational superiority of

the British. The movement infused the marginalized or disadvantaged communities

of South Thiruvithāṅcūr with confidence, coordination, and emancipatory

energy.” (349)

In

the same section, the contribution of another important social reformers from Kerala

was thoroughly discussed: Śrī Nārāyaṇa

Guru who is considered as ‘the most sterling instance of how spirituality could

affect a tremendous social uplift of an entire community and hence make the

whole society more just and more humane’. He emphasized the concept of ‘Svabhāva-Svadharma’

in determining one’s individuality and compared human species as one ‘Jathi’.

The author quotes him:

Of

a socially excluded woman

was

born the great sage

Parāśara

in those old days.

And

even the sage who

Condensed

the Vedic secrets

Into

great aphorisms

Was

born of the daughter of a fisherman.

Species-wise,

does one find,

When

considered,

Any

difference between man and man?

Is

it not that

Difference

exists apparently

Only

individual-wise? (406)

Nārāyaṇa

Guruopened up several temples throughout South India along with Veda Pāṭhaśālā

for the study of Vedas and Upaniṣads, rooting his social reforms

in Indic ethos. He also played a crucial role in raising awareness about

untouchability in Kerala, had decisive influence on other national leaders,

including Gandhi, who were advocating the rights of temple entry for all

Hindus, without any discrimination.

The

Temple Entry Movement

The

author has brilliantly highlighted the role of Mahatma Gandhi in this struggle

of certain sections of Hindu society to gain entry into temples; it is one of

the most important sections of the book. It is a section that every Indic

seeker must read to understand the complexity behind the whole issue and role

played by several leaders to bring the requisite social reforms. I must admit

that I was completely ignorant of this part of Indian history where social

stagnation, in the name of orthodoxy and pseudo-scriptures, were justified and

every attempt was made to scuttle the temple entry to marginalized and

depressed sections of society.

Not

only leaders like Nārāyaṇa Guru and Mahatma Gandhi succeeded in opening up

entry into temples for all sections of Hindu society, but also defeated the

nefarious design of missionaries in converting these Hindus. Hindu society must

always remain grateful to these leaders, without them a large section of our

society must have got converted into alien faiths, leading to innumerable

divisions of society. Aravindan pertinently mentions the words of Natarāja

Guru, underscoring the importance of the social works of these national

leaders:

“Dayānanda

stressed the importance of the Vedic and Aryan virtues of equality; Vivekananda

defended Hinduism primarily in the name of mother-worship of Kālī; Gandhi

stressed Vaiṣṇava democratic notions in public life; and Tagore sang songs

breathing something of the freedom of the Upanishads across modern India—all of

them aiming at raising the status of India in the world. The silent Guru of

Varkala, sitting on a hilltop at the southern extremity of Mother India,

steeped in the silence of non-dual unitive vision, integrated all the

contributoryviews and visions into one whole, brought all within the scope of

one contemplative Word-wisdom, by which human dignity could be held high

everywhere and all mankind become free.” (415)

One

must ponder that why these contributions have never been taught in our textbooks,

as an indigenous examples of social reforms, rooted in Indic ethos; why Marxist

historians always focused on nurturing perpetual conflicts among sections of

Hindu society and never on including successful case studies of social harmony

and justice, elevating all sections of society. The reason is simple: they

never cared about social justice, but only on social upheavals and chaos;

eventually using it to gain political power.

Looking

at India through the lens of Marxism and its successor ideologies has never

given any scope of understanding India’s complex history, through various ups

and downs, where colonial invasions broke social harmony and unleashed various

forces of social stagnation. The colonial draining of wealth had disastrous

impact, leading to impoverishment. The most unfortunate part in this whole saga

is, rather than blaming invaders, all faults and guilt were attributed to Hindu

society. In fact, the history of India is yet to be written through the

perspective of Hindu agonies and suffering; and what wounds it inflicted upon

them.

Social

Reforms during Freedom Struggle

India

suffered social stagnation through colonial interventions, but fought back and

resisted through indigenous dhārmika approach. It threw leaders, in such

challenging times, who all raised awareness about social changes in Indic mode.

The various issues of depressed classes were resolved, which originated due to

colonial manipulation, were taken with utmost sympathy by leaders well-grounded

in Indic ethos; appealing society through Indic vision of cosmic unity.

The

journey of Annie Besant in this regard is quite illuminating; having taken a

rigid stance in the beginning about the entry of depressed students in schools

due to her colonial approach, she eventually changed her mind and helped in

passing a resolution against untouchability. Aravindan notices: ‘It is worth

noting that the Hindu social reformers then outshine their British counterparts

in their commitment to human equality.’

The

various national leaders played an important role in passing a resolution

against untouchability, despite resistance from some orthodox quarters. Vitthal

Ramji Shinde, Sayajirao Gaekwad, Balgangadhar Tilak were a few important

luminaries whose stories are discussed, with all subtle nuances. If Shinde

emphasized on modifying the categories that created varṇa distinction,

then Gaekwad appealed to raise social awareness about discriminations and

countering them with teachings of Bhagavad Gītā, and Tilak’s recognition

of a devolution of caturvarṇa in India into a ‘mere birth-based

division, forgetting the duties’; and his scholarly commentary on the Bhagavad

Gītā removed any misconception regarding individual and varṇa,

recognizing caturvarṇaas archetypal division, not Indian exceptionalism;

and finally Swami Sahajananda speeches on necessity of opening up temple for

Harijan, claiming that no Shastra prohibits this.

An

interesting section on inter-caste marriage bill also gives us the dynamic nature

of society, wherein orthodox section proclaimed this as the collapse of varṇāśrama

dharma. On the other hand, various national leaders promoted the bill to

remove the ‘water-tight compartment’ of Indian society. Lala Lajpat Rai

supported the bill, challenging the social stagnations in Hindu law because of

colonial mindset:

“The

Śāstras made ample provision for the legal recognition of these changes. It is

the rigidity and absurdity of the Judge-made law of the British Courts that has

brought about the existing impasse in the marriage laws of the Hindus. A change

such as is contemplated is an absolute necessity. Opposition to it is based on

short-sighted partisanship and false notions of Dharma.…It is sheer dishonesty

to oppose this reform on the ground of its being dangerous to Varṇāśrama

Dharma, while the latter is a mere caricature of its original

self. Unless we propose to live forever and ever in our present degraded

condition, it is absolutely necessary that our ideas of Varṇāśrama

Dharmashould be radically changed. Political democracy is a

myth unless it is based on social and economic justice”. (464)

In

this context, Sri Aurobindo’s penetrating analysis on the outdated medieval

Hindu laws, created as a survival mechanism, and therefore an urgent need of

changes in them is worth mentioning:

“In

answer to your request for a statement of my opinion on the inter-marriage

question, I can only say that everything will have my full approval which helps

to liberate and strengthen the life of the individual in the frame of a

vigorous society and restore the freedom and energy which India had in her

heroic times of greatness and expansion. Many of our present social forms were

shaped, many of our customs originated, in a line of contraction and decline.

They have their utility for self-defense and survival within narrow limits, but

are a drag upon our progress in the present hour when we are called upon once

again to enter upon a free and courageous self-adaptation and expansion. I

believe in an aggressive and expanding, not in a narrowly defensive and

self-contracting Hinduism”. (465)

Hindu

Laws: Are they set in stones?

This

brings us to the crucial issue of required changes in Hindu laws. Are these laws

set in stone, or have dynamism that makes them open and flexible for changes?

Can we claim immutability of every aspect of Hindu laws, dictated by primordial

scriptures and henceforth not to be touched? Or historically, what brought

social stagnations in Hindu laws and how to overcome them when circumstances

are changing? Both Lajpat Rai and Sri Aurobindo hinted at the colonial–Islamic

and British–impacts on our existing laws, and therefore nothing sacrosanct

about them. These changes are not going to disturb the foundation of Hinduism,

but will help us get rid of later accretions, not connected to the original

spirit of Dharma.

The

legendary King of Baroda Sayajirao Gaekwad III was one of those figures who

tried to implement this vision, ushering in what the author has dubbed as ‘the

Baroda Model of Social Reforms’. This is one of finest sections to read,

wherein Gaekwad's role as a ruler, reformer and visionary come out prominently;

setting wonderful examples of indigenous reform mechanisms.

In

all these examples of social reforms, one can see the strong foundation of

Dharma as the force of social emancipation overcoming local prejudices and

sectarian conflicts. It also involved challenging the so-called immutable

aspect of caturvarṇa. The author shares writings of national leaders,

engaged in social reforms, proclaiming the devolution of varṇa-jāti,

from fluid, open and flexible system into rigid hierarchies of caste. All

these leaders were unanimous in asserting the Vaidika and Upaniṣadika wisdom of

oneness, stated in the famous mahāvākyas as the true grounding of Sanātana

Dharma.

Furthermore,

there is an interesting section on the different approaches taken by these

leaders. Dr. Ambedkar was eager to have a separate electorate on the lines of

religious minorities, while M. C. Rajah always demanded for a joint electorate

with reservation to bring social integration. The tireless efforts of MCR

for social reforms from within, considering Depressed Classes as no less a

Hindus than elite class, set an excellent example for Hindu social justice. In

fact, the Rajah-Moonje pact became a cornerstone for further social reforms in

India; much ignored in any contemporary social discourse. It is quite

remarkable that Dr.Ambedkar's harshest criticism against Hinduism did not stop

him in grounding social reforms only through the Indic approach, reflected in

his usage of the Indic concept of Mitra

and Brāhmaisminstead of western

concept of fraternity and equality.

Hindu

Reforms: Social Awareness or Legalization?

The

need for raising social awareness instead of solely relying on legal measures

for social justice is emphasized by many of these leaders including Gandhi and

Rajagopachari; and wherein they succeeded immensely. Aravindan aptly summarizes

this unparalleled success, in context of temple entry movement:

“...C.

Rājagōpalachāriyār made temple entry by taking into account all dimensions: the

social, the peculiar colonial legal stagnation of Hindu law and mentality,, the

importance of social emancipation for national liberation, the social harmony

achieved without compromising on social justice, the healing of society from

the social evil of untouchability, not only by the astute manoeuvres taken by

C. Rājagōpalachāriyār with his absolute conviction in social justice but also

through the role of constructive, completely justified, aggressive criticism

and relentless efforts of M.C. Rājāh. Today, access to temples is taken for

granted by all Hindus, but this self-evident democratization of spiritual space

was brought about by the greatness of such selfless individuals, all inspired

in their own way by Sanātana Dharma.” (575)

These

reforms, as stated earlier, had foiled the design of missionaries to convert

Hindu masses. The life and work of BabuJagjivan Ram is very important in this

regard, the author highlights:

“Jagjivan

Ram was clear in his vision. He believed that the Scheduled Castes masses

considered themselves Hindus and that they had sacrificed much for the cause of

Hinduism. At the same time, he through his organization ‘pressed for special

representation in the legislature and in the services in order to enable the

Scheduled Castes to raise themselves to the level of the rest of the country’.

In February 1936, he passed a resolution at All India RavidasSammelan stating

that religious conversion was not a wise decision and that ‘Dalits’/’Harijans’

would remain within the Hindu fold and fight for their rights.” (542)

It

is due to his life-time dedication of social upliftment through a dhārmika

approach that ‘prevented the conversion movement from gaining traction in

Bihar.’

Indic

Social Sciences: An Urgent Need

We

have seen that, in every epoch of India, the finest minds arose against social

stagnations believing in inherent spiritual strength to overcome temporary

discriminations. The author vividly captures the spiritual undercurrent

coursing through five millennia of India shaping social discourse, embracing

every section of society. This book is unparalleled in many respects - –the

vast timeline it deals with, the breadth of examples it narrated, the various

nuances it highlighted with all grey areas- makes it one of the most profound

works of our time. Indeed, it sets the stage for future research on Indic

Social Sciences, an area that is still dominated by alien perspectives,

having no connection with Indian reality. We must get rid of alien concepts,

prevalent in current academia, such as Positivism, Secularism, Structuralism,

Post-Modernism etc. that do not help in capturing the social reality of India. Such

work is an urgent need for Hindu society, as all policy making at the national

and state level is still influenced by core ideas in colonized frameworks of

the humanities department.

Aravindan

has shown us the way, with massive evidence, to decolonize social sciences in

India. In the concluding section, he has pointed out the research of various

prominent scholars like Sri Aurobindo, Prem Saran, Nirmal Kumar Bose, McKim

Marriot, Ronal Inden etc. that can help in this gigantic task of creating a new

paradigm for ‘A Hindu Model of Social Evolution’. The model should be appropriate,

organic and drawn from the historical context of India, which captures the

inherent dynamism of civilizational complexity. It must look at India through a

multidimensional perspective, though grounded in the overarching principle of

Dharma, to understand the healthy balance between individual and society,

self-development with social prosperity, unifying principles with decentralized

structure and economic growth with ecological consciousness.

May

Aravindan's works become a guide for all of us in this direction, with an aim

to decolonize the Indian mind and help them discover the original spirit of

Sanātana Dharma in service of society!

- 280 min read

- 2

- 0