- Visitor:578

- Published on: 2025-02-17 05:20 pm

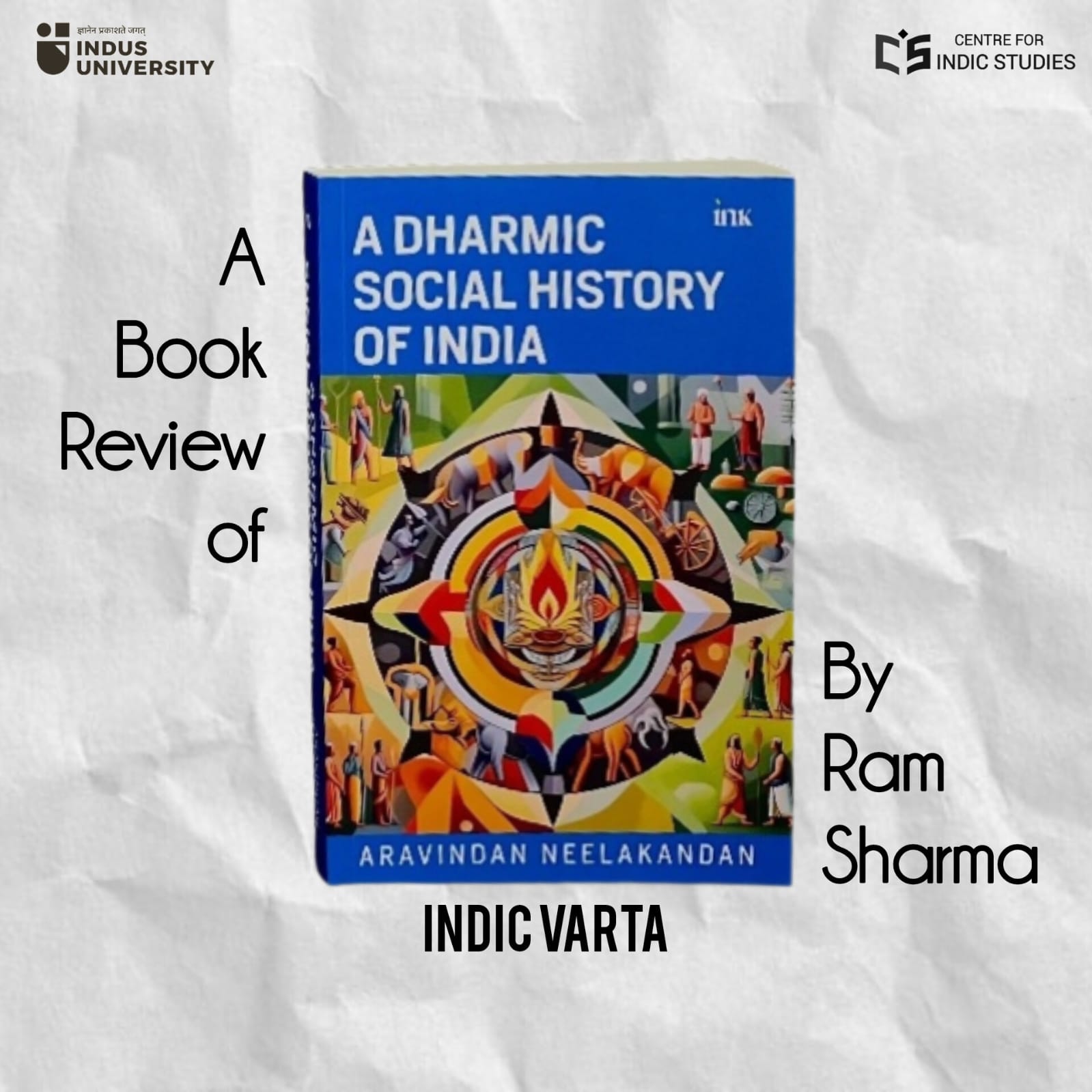

A Book Review of Aravindan Neelakandan’s A Dharmic Social History of India (Part I)

What does India stand for? What is the most important insight of Indian civilization that pulsates through every aspect of its manifestation? What can be counted as the central pillar of our civilization, laying a strong foundation for millennia?

Since colonial Indologists began defining us,

the caste system and its allied social organizational framework have been

promoted as the core defining feature of Indian civilization. According to

these colonial stereotypes, Indians are obsessed with caste identity and the

‘social status’ it provides within a hierarchical ladder, leading to notions of

superiority among certain classes and subsequent oppression.

This

notion, fed and reinforced repeatedly over centuries, became an inalienable

feature of any discussion on Indology. The same stereotypes were carried

forward by various academic ideologies that dominated Indian academia—from

Marxism to Postmodernism. While the outer form of their presentation kept

evolving, their core conception of Indian society remained stagnant and stale.

This is

not surprising, as their alienated dṛṣṭi

(perspective) and prejudiced minds never allowed them to delve deeper into the

sublime Indic vision of cosmic unity.

However,

what is truly surprising is that we ourselves began to internalize this ‘caste’

narrative as the core essence of our civilization. This happened not only

through colonial education but also among those who had long resisted such

colonial stereotypes. In a strange twist of colonial exchanges, what should

have been consistently exposed as the worst misrepresentation of indigenous

society was, instead, accepted in post-colonial studies and even by certain

sections of indigenous scholars.

Nevertheless,

let me state that this issue is not confined to colonial studies alone. The

most essential features of civilization and their impact on society take us to

the heart of understanding the underlying principles of social dynamics. They

lead us to examine social structures and the harmony embedded within them, the

forces that drive social change and adaptation, and the sustaining elements

that have upheld societies for millennia. Most importantly, for us, they reveal

how these dynamics unfolded in the context of Indian civilization over several

centuries.

Aravindan Neelakandan, the well-known erudite scholar takes us with his new book titled A Dharmic Social History of India on a 5000-year-long journey of Indian civilization, dealing with the crucial topic of social dynamism that has shaped and molded Indian society. It provides unparalleled insights into how our society has dealt with various changes and sustained itself with harmony and peaceful coexistence. The importance and seriousness of this book are underscored by the Vedic scholar, Dr. R. Rangan, in the wonderful preface of this book:

"We are, as a nation and civilization, at a critical juncture. Many

biased and malicious-intentioned works, both in academic institutions and

media, blame Hindu Dharma for the social exclusion of marginalized communities

and their sufferings. This confuses thinking and righteous-minded Hindu youths

as to what is the real nature of Hindu Dharma with respect to the question of

social inequalities and social liberation. For such perplexed Hindu youths,

this book is ambrosia. To the thinking and conscientious Hindu youths, this

book brings awareness about the matchless contribution of Hindu saints in

uplifting the downtrodden and shows this as the path to be continued in the

future. If we do not follow this path, we will certainly perish."

This

book is certainly a guiding force for seekers in clarifying one of the most

distorted areas in Indic studies—social structure and harmony in India.

The contribution of any writer is gauged

and found impactful when he provides a new perspective or ‘paradigm shifts’ in

our existing framework, introducing key concepts that can reorient us in our

exploration. Aravindan has done precisely this in his analysis of India’s

social dynamics. A subject that has been framed only through Western

universalism—imposing the eternal binary of oppressor and oppressed—is

thoroughly challenged and demolished. He leads us, through scores of evidence,

to a fresh perspective on society, using an evolutionary paradigm along with a

Dharmic framework—a task that has never been attempted before and is therefore

unique in its scope and exploration.

Stratification

and De-stratification

He

introduces two social forces that have shaped social dynamics over centuries in

India, or for that matter, in any civilization—the forces that bring social

stagnation and those that lead to social emancipation.

Society remains in flux, continuously

changing, adapting, and reconfiguring due to various historical reasons. The

forces of social stagnation often lead to rigidity, prejudices, and disharmony

in society. On the other hand, the forces of social emancipation result in

freedom, openness, flexibility, and harmony. How these forces have played out

in India is the core theme of this book.

In a way, Aravindan uses the traditional

taxonomy of Śruti

and Smṛti to

explore how Indian society has navigated the various ups and downs of its

social journey. This wise and powerful taxonomy has allowed Indian society to

remain anchored to absolute truth while also helping it navigate inevitable

social changes over centuries. The Śruti

texts—primarily the Vedas—have

anchored Indians to the ultimate goal of life, rooted in the vision of cosmic

unity and non-dual consciousness. The transmission of these texts has kept the

core wisdom alive and intact. On the other hand, the Smṛti texts—primarily the Dharmaśāstras and Smṛtis—were meant to guide

society through various changes. They take into account continuous changes and

respond to them through various prescriptions, depending on deśa (space), kāla (time), and paristhiti (circumstances). However, in this book, the author has relied

on the historically contingent practices of the living spiritual tradition,

rather than textual tradition of Dharmaśāstras,

as the guiding force for social dynamics.

This unique division of the knowledge

system has neither deviated Indian society from its fundamental principles nor

allowed it to become a ‘hotchpotch’ of multiculturalism, a mass of confused

identities. On the contrary, Indian society neither got stuck in an idealized

past nor became rigidly obsessed with blindly following ancient rules.

India’s

Forgotten Social Revolution

Indian

society has witnessed the negative impact of social stagnation but has tried to

overcome them with the liberating forces of social emancipation, rooted in dharmic

practices. Unlike the history of the Western world, which is full of

disruptions and studded with revolutionary movements to bring changes in

society, Indian society has always believed in gradual and subtle changes,

integrating transformations in a non-violent and harmonious manner. Aravindan

aptly brings this to our notice:

"While most revolutions that defined the modern age—from the

French Revolution to the Maoist Great Leap—have generated extreme human misery

and violence, and their effects were short-lived, the revolution that the Bhagavad Gītā was a part of, namely bhakti, became the most sustained social

transformational movement against the human societal tendencies towards social

stagnation and social exclusion. This unfolded through the history of India,

through millennia, in a unique decolonized way."

This

important insight captures the Indic way of social transformation, which is

mostly ignored by intellectuals in social studies. Even a superficial glance at

the existing literature on

Indian social history reveals numerous invasions, but hardly any violent

revolutions from within that caused large-scale disruptions. It is a strange

neglect from the perspective of modern academic studies on Indology, where tons

of material have been published regarding discrimination and oppression in

Indian society.

In this context, it is pertinent to mention the work of

Martin Malia, History’s Locomotives: Revolutions and the Making of the

Modern World, which documents revolutions in the Western world as engines

of social change and the havoc they wrought. It makes us ponder how the Indic

way managed to shape a trajectory different from that of the West and the

reasons behind it.

Universality of Social Straitification and Western Hypocrisy

A

series of myths that Aravindan debunks while analyzing the standard model of

Indian social history is quite illuminating. The first myth he exposes is the

claim that dividing society into groups or castes is an exclusively Indian

phenomenon. This idea of exceptionalism has been promoted by colonial

scholars as well as their indigenous opponents. Aravindan refutes this notion

by providing examples of hierarchical social divisions across the world. He

argues that all pre-modern societies had some form of birth-based social

stratification, often leading to discrimination. This is evident even in a

cursory glance at occupational groups in medieval Europe, many of which persist

today in surnames such as Barber, Taylor, Butcher, Smith, and Cooper.

Every pre-modern society created social divisions based on

occupation, primarily for the smooth functioning of the economy. Guilds and

community organizations were responsible for the effective distribution of

resources. In many societies across the world, these birth-based divisions led

to the worst forms of oppression, often justified in the name of racism and

theology. The author narrates many such examples: from medieval Europe, where

the hardship of peasants and serfs was justified as atonement for their sins;

to Islamic society, which divided people into Ashraf and Ajlaf

based on lineage traced to the Prophet Muhammad; to China, where the Hukou

system has perpetuated serfdom even in the 21st century, leading to widespread

exploitation.

Such examples can be multiplied abound in case studies of

various other civilizations, where social divisions led to stagnation but were

often ignored or brushed under the carpet. The irony is that while a massive

academic industry has emerged to make Hindus feel guilty about social stratification,

other societies are seldom discussed, merely acknowledged in passing, or their

injustices completely ignored. However, lest it be misunderstood, the

injustices in other societies do not justify those in India.

Hence, one must study societies using the framework

suggested in this book and reflect on what prevails in the long run in

India—whether it is the forces of social stagnation or those of social

emancipation. A comparative study of civilizations can provide more clarity on

universal social dynamics. Aravindan pertinently observes:

"In fact, it can be said that no other religious/spiritual

tradition has consistently questioned the social status quo through its

spiritual values as Hindu Dharma has done. In the West, social stratification

became irrelevant when colonialism brought in the vast inflow of capital and a

huge expansion of land and natural resources... In other words, the apparent

egalitarianism seen today in the West has come at a great cost to all of

humanity in terms of extreme misery and suffering. It has been obtained by the

West only as a transactional exchange in human suffering. The consequences of

this transfer of human misery continue well into the present centuries."

Therefore,

it was not altruism but rather the shifting of exploitation from their own

people to the others that enabled the West to eradicate slavery. Is this

model of social emancipation valid for all times? Is the Western

approach—converting slavery into indentured labor and, subsequently, seeking

cheap labor across the world—a sustainable model of social emancipation? Or are

there alternative ways, perhaps Indic ways, to overcome the forces of social

stagnation? Aravindan raises fundamental questions regarding social injustices

and their long-term solutions.

In exploring these questions, he proposes an urgent need for

Hindu Social Sciences from a dharmic perspective, rooted in indigenous

traditions. This age-old knowledge system must be integrated with insights from

modern biological sciences, shedding light on the evolutionary nature of social

dynamism and its functions across not only human societies but other life forms

as well. In this context, the author mentions the works of J.B.S. Haldane,

Nirmal Kumar Bose, and others, directing us toward an alternative approach to

social studies. These scholars particularly emphasize the integration of the Puruṣārtha

framework—the multiple goals of life—with evolutionary dynamics, highlighting

the Hindu model of harmonizing differences, leading to unity in multiplicity.

Such integration is essential because “It emphasizes the connection of culture

with basic human needs and desires... which underlies all cultural phenomena.”

Re-interpreting

Harappan Society

Another dominant narrative propagated through

the colonial framework is that inequities and social injustice have been

embedded in Hindu society from the very beginning. Whether one considers

primordial texts like the Vedas or the first Indian civilization, such as the

Harappa, both are alleged to have laid the foundation for centuries of

discrimination.

Thus,

it is argued that the worst forms of inequality are rooted in the original

Hindu scriptures, thereby denying any scope for later accretions or

misinterpretations. As a consequence, it is proposed that the only remedy to

this evil is that the entire foundation of Hinduism must be

"dismantled" or, in academic terms, "deconstructed" to

liberate the masses. The typical template for any social revolutionary is thus

ready to be worked upon—no need for further analysis.

Seen

from this perspective then, Harappan

society has always been depicted as a "totalitarian and oppressive

regime" controlled by Brahmins, leaving no scope for individual creativity

and leading to "monotonous regularity." Scholars do not mince words

in expressing their disdain for Harappa, as reflected in this statement by

Stuart Piggott: "I can only say that there is something

in the Harappa civilization that I find repellent." (42)

Drawing inspiration from exclusive

religious frameworks, these scholars cannot digest the assimilative nature of

Hindu society. For them, Brahmanism is all-encompassing and, therefore,

threatening. The author highlights the intense hatred of some of these writers

by quoting Caldwell’s apprehension: "Brahmanism repudiates

exclusiveness; it incorporates all creeds, assimilates all, consecrates all…

thus Brahmanism yields and conquers." (44)

In contrast to such depictions, recent

studies borrowing insights from archaeology, genetics, linguistic modeling, and

cultural anthropology present a far more nuanced and multipronged picture.

Harappan society is now shown to have had a decentralized structure, with a

continuous flow of information and goods across hundreds of miles, built on an

exceptional social framework that was both dynamic and harmonious. Aravindan,

through various studies, demonstrates the reciprocal nature of resource

distribution, indicating an egalitarian society rooted in complex cultural

dynamism. He summarizes: "What emerges is a picture

of a multilingual, non-monocultural Harappan civilization, one that embodies

the spirit of unity in diversity that has been present in this land since

ancient times." (58)

The

Concept of Yajña

If

the reality contradicts colonial stereotypes, then the author raises very

pertinent queries, stating:

"Had Harappan society been characterized only by hierarchical authority, solely based on ritual power and heredity in a pyramidal manner, as the Varṇa system is often characterized, then it would have displayed the power and splendor of the upper sections of society in sharp contrast to the deprived sections. Archaeological data does not suggest such a gulf dividing the society. For a society to function for millennia, there must have been a system of reciprocal redistribution. What was it? Can we identify it?"

In

response, he presents the most important insight of the book. He argues that

the decentralized nature of society and its reciprocal exchanges of resources

were driven by the concept of Yajña

and Yajamāna,

which later reflected in the Indic tradition of the Yajamānī system. Any Indic seeker can connect

to the deeper imagery and symbolism of Yajña.

The ritual of Yajña

holds multilayered associations in the Indic mind, ranging from sacred

offerings to the elevation of even the most mundane tasks to larger social and

cosmic goals. For us, every righteous task undertaken is an āhuti (offering) for cosmic

welfare. The author observes: "Yajña, or the Vedic fire ritual, forms an archetypal basis for Indian

civilization. It is not just about offering material things to various deities,

but it is also the co-creation of the Universe as a continued process." (77)

Aravindan connects these connotations

through various Harappan studies conducted by less prejudiced minds,

highlighting insights from eminent scholars like J. Kenoyer, Jane McIntosh, P.

Parthasarathi, and B. Kovler. These scholars emphasize that Harappan

civilization must have been based on “relationships of reciprocal exchange,” in

which "all members of the community have reciprocal

obligations to provide the products of their labors." They

often ponder how such an amorphous system—"semi-hierarchical, semi-heterarchical"—could have existed

and functioned smoothly.

Yajña serves as an archetypal basis for all

reciprocal exchanges, rooted in the vision of cosmic unity, where every

activity becomes a Yajna.

In the words of the author:

"Fine arts, dance, drama, and all other activities become Yajña. This means that a dancer, a carpenter, a farmer, a merchant, a

barber, a washerman, a potter, and all other professions can be the Brahmin

performers of their Yajña, and those who utilize their skills and knowledge become Yajamāna. This Yajña archetype behind every vocation has the potential to make all work

sacred and none defiled. This also means that social exclusion and social

aristocracy can be challenged by such a value system whenever social stagnation

leads them to inhuman proportions."

The

metaphor of Yajña

emerges as a powerful force of social inclusion and, when needed, a spiritual

tool for social emancipation—a tool that laid the foundation of Vedic society,

driven by the utmost compassion to integrate all and exclude none. Therefore,

quoting isolated passages to justify discrimination amounts to a falsification

of the true spirit of Sanātana Dharma.

Aravindan

thus corrects the misleading use of the Puruṣa

Sūkta and exposes the hidden agenda behind its nefarious

misinterpretation. He highlights Dr. Ambedkar’s research, particularly his

assertion that this sūkta

is a cosmogonic hymn rather than a social verdict. Additionally, he underscores

the primacy of Dharma

over all Varṇas,

as stated in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka

Upaniṣad, to dispel any misconceptions of superiority among social

groups—a point highly relevant to discussions of social inclusion.

Origins of the

Buddhist-Hindu Divide Narrative

The

next colonial narrative that became entrenched in Indian academia is the

portrayal of Buddhism as a reformist movement in India, ultimately liberating

the masses from the tyranny of Brahmanical oppression. Colonial scholars,

rooted in Christianity, felt more comfortable dealing with prophetic Buddhism

despite its origins in so-called ‘heathendom.’ They mapped this onto their

Western universalist framework, positioning Buddhism as the Protestant

equivalent in India, with the divine task of uprooting the Brahmanical

priesthood, much like Protestantism sought to challenge the Catholic Church.

This resulted in what the author describes as "the creation of a Buddha of

ancient India that was more Christological and Lutheran in nature."

In this colonial zeal to rewrite Indian

history, Aravindan aptly points out: "The more Buddha is portrayed as a Lutheran figure, the more Hinduism is

depicted as an oppressive religion" (101). This distortion, like many other colonial attempts to

create fault lines in India, did not remain confined to academia and had

pernicious repercussions on the ground. If Buddhism was portrayed as more

Christ-like, then Bodh Gaya was also promoted as the ‘Jerusalem’ or ‘Mecca’ of

Buddhism, supposedly held in the clutches of a regressive Hindu community. The

author narrates the role of Anagarika Dharmapala, a Sri Lankan Buddhist

scholar, who dedicated his life to following in the footsteps of colonial

masters. Through his magazine, The

Mahā Bodhi, he consistently depicted Hindus as encroachers, steeped

in ignorance and superstition, arguing that they must be expelled from Bodh

Gayā.

This section of the book is an

eye-opener, exposing various layers of colonial hatred, which were

enthusiastically adopted by certain indigenous scholars. This narrative

ultimately contributed to the massacre of thousands in Sri Lanka and paved the

way for the contemporary diabolical propaganda of the neo-Buddhist Ambedkarite

movement in India. To grasp the full extent of this false narrative, one must

read the following passage:

"Bodh Gayā can thus be considered one of the main fountainheads of the

genesis of the modern deep schism between Buddhist and Hindu identities, with

particularly far-reaching consequences for the Tamil (mainly Hindu) minority in

the island nation of Sri Lanka. A reinvented Buddhist identity, shaped through

colonial Indological frameworks, served as its religious fulcrum in the

Sinhalese racial political revival. This was inevitably accompanied by an

anti-Hindu sentiment, which became a significant, albeit not exclusive, catalyst

for what would become, in post-colonial Sri Lanka, a protracted civil war. The

conflict was characterized by numerous anti-Tamil pogroms, military aggression

and abuse against Tamil civilians, and suicide bombings orchestrated by the

Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), targeting Sinhalese civilians and

leaders. The conflict further escalated with the assassination of a former

Indian Prime Minister on Indian soil by an LTTE suicide bomber, the recruitment

of child soldiers by the LTTE, and their use of Tamil civilians as human

shields. The Sinhalese army’s actions included aerial bombing of civilian

targets, including designated safe zones, systematic sexual violence, and the

execution of not only surrendered Tamil fighters but also civilians. The conflict

culminated in the infamous Mullivaikkal Holocaust of 2009, which resulted in

the massacre of over 30,000 Tamils, predominantly Hindus. This event

underscores the devastating human cost of this conflict."

Is

Buddhism Egalitarian?

The

final narrative in this series, one closely related to the Lutheran Buddha

framework, is the claim that Buddhist texts and discourse always advocated

equality, never differentiating between communities. Aravindan refutes this

claim using primary scriptures such as the Vinaya

Piṭaka, the Lalitavistāra

Sūtra, and the Ambaṭṭha

Sutta, demonstrating that conceptions of high and low birth-based

stratification existed in Buddhism from the time of the Buddha himself.

In fact, he argues that birth-based

divisions only deepened due to the ‘defilement’ of certain occupations such as

scavenging, hunting, cart-pulling, and weaving. He makes a compelling case for

the unintended consequences of ‘certain ethical excesses,’ which stemmed from

an exclusive focus on ahimsa

(non-violence), even in worldly affairs. This perspective, he asserts, shaped

Buddhist attitudes and perceptions toward many of these castes (129). In this

context, the Belgian Indologist Dr. Koenraad Elst’s talk on Buddha and Egalitarianism,

available on the YouTube channel of the Centre

for Indic Studies, is highly pertinent.

The

author also explores how this defilement of certain occupations contributed to

the institutionalization of slavery within Buddhist monasteries. He provides

historical examples ranging from the Buddhist communities of ancient Mathura to

the Pagodā slaves

of Myanmar. This must be understood in the context of the centralization of

monastic culture, where hundreds of monks lived together, necessitating the

presence of ‘attendants’ from the time of the Buddha himself. The historical

evidence of a Buddhist-led social reform movement is almost nonexistent. This

is evident to the Indian mind, which has never viewed the Buddha as a social

reformer but rather as a spiritual mentor. Aravindan pertinently quotes Dr.

B.R. Ambedkar: “When the Buddha differed from the Vedic Brahmins,

he did so only in matters of creed but left the Hindu legal framework intact.

He did not propound a separate law for his followers.”

Aravindan

presents a broader societal reality while discussing this issue, summarizing it

in the following words:

"Social inferiorization, as well as social exclusion of communities, is

found in Buddhist societies both in South Asia and in other Asian countries.

This should be seen more as a complex interaction of Buddhist worldviews,

values, and the social evolution of localized settings. Similar trends in

social evolution were present in pre- and early-modern Christendom. Hence, this

is in no way peculiar to Buddhist societies. The problem arises because of the

constant portrayal of Buddhism as an egalitarian movement while simultaneously

essentializing non-Buddhist Hinduism as almost nothing but ‘Brahminical’

superiority."

The

essentialization

of one community over another—pitting them against each other—has been a

time-tested template of colonial forces. This manufactured narrative of

Hindu-Buddhist antagonism is a clear reflection of such colonial strategies.

The author has brilliantly deconstructed these distortions using primary

evidence and historical facts, providing readers with a deeper understanding of

social dynamics. He first dismantles the false narratives that have become

deeply entrenched in academia and media, making it nearly impossible for any

seeker to comprehend the true picture of Indian society. He then moves towards

reconstructing an Indic perspective on social dynamics, presenting an

understanding untainted by colonial prejudices.

Reconstructing

the Indic Narrative of Social Justice

After

busting these four popular myths that are deeply entrenched in academia, he takes us on a journey

through India's social history from a Dhārmika

lens. Without denying the existence of social stagnation in India, he examines

the broader spectrum of social emancipation, which has acted as an inherent

corrective mechanism to overcome hate, prejudice, and discrimination in Indian

society.

While discussing the trajectory of Indian

social history, one must not forget that India is the oldest civilization, with

a continuous existence of various living traditions for thousands of years.

This implies that any social study conducted through a mono-prismatic and

exclusive lens will inevitably lead to gross simplifications and distortions.

Need for an Indic Framework

Indian

social history demands the rigor necessary to explore the complexities of

civilization without surrendering to fashionable ideologies, which are often

driven by motives to destabilize Indian society. This exploration makes sense

only if we go to the roots of Hindu civilization—the foundational principles of

social structure, based on the cosmic vision of the Vedas. We have also hinted that the concept of Yajña and the co-creation of cosmic and social reality have been

archetypal for Indian tradition. This archetype, rooted in the Vedas and

nurtured through the presence of self-realized souls, has continually

transformed the ideal of cosmic unity into social egalitarianism. The concept

of Yajna gave birth to many other spiritual archetypes in India, one of which

is the illustrious Bhakti tradition,

found in every nook and cranny of the country, binding devotees into spiritual

communion through their intense yearning for the beloved deity. Aravindan

highlights this:

"Bhakti is portrayed as a remarkable

civilizational endeavour aimed at rectifying any doctrinal corruption. It laid

the foundation for future social movements in India, ranging from Khalsa to

Gandhi. While social emancipation was not the primary objective of Bhakti, it

inevitably brought about societal liberation as a natural consequence with

minimal or almost nil violence and sustained community elevation." (142)

It

must be emphasized and appreciated that Aravindan has rightly pointed out that

the purpose of Bhakti is not to bring about social reforms; therefore, it

should not be seen as a "movement" in which one section of society

leads a "revolt" against another. Social emancipation happens

naturally around those who selflessly pursue the path of divinity, merging

themselves with the ‘ekam sat’ and

embodying the principle of oneness. The presence of self-realized souls, who

have transcended all social identifications and focus on the ultimate divine

within, has challenged social stagnation and the status quo by repeatedly

questioning the act of social exclusion.

Bhagavad Gītā – A Guide for Social Emancipation

The

author underscores the importance of the Bhagavad

Gītā and the Mahābhārata, in

continuation of Vedic wisdom, in making us realize the complex dynamics of

society, the inherent fluidity of social changes, and the resultant inadequacy

of imposing fixed categories. Through various dialogic narratives, the Mahābhārata

repeatedly highlights the rigidity of varṇa

classifications, challenging the simplistic notion of birth-based

stratification.

One

of the key inquiries is the essential defining traits of a Brahmin. This

question is posed repeatedly, emphasizing that "conduct, practice, and

qualities" are the primary markers for social identification rather than

birth. The famous story of Dharmavyādha, in which a butcher, by diligently

following his worldly duties, attains enlightenment and becomes a mentor to a Brāhmaṇa, reverses traditionally

assigned roles. The text also makes a case for a Shudra attaining the status of

a Brāhmaṇa through his conduct. At

the same time, this narration, like many others in Hindu texts, elevates the

status of every occupation, making all professions co-creators of social

reality—unlike the Buddhist worldview. Aravindan writes: “While the Buddhist

worldview demanded that butchers and meat sellers be considered untouchables,

here, ‘twice-born’ people direct the Brāhmaṇa Kauśika to the meat shop of

Dharmavyādha.” He further elaborates:

"In the background of the notion of noble

professions and defiled trades, the epic speaks for equal nobility within all

professions and trades. Every trade can be a Yajña, and in all birth-based communities, persons can be of Brāhmaṇa

nature and become the authority for dharma. From them, others, however highly

placed in society they might be, should learn. It is within this value system

of spiritual equality that the Bhagavad

Gītā is placed."

This

takes us to the philosophical discourse of the Bhagavad Gītā, embedded in the larger narrative of the Mahabharata,

which expounds on the value of svadharma

and svabhāva in determining social

identity. This section of the book is particularly insightful in peeling the

nuances woven around the concept of varṇa-saṃskāra.

Aravindan highlights the central role of the Bhagavad Gita in challenging

social stagnation through its continuous emphasis on "guṇa-karma-vibhāgaśaḥ" as the major determinant of jāti-varṇa. Aravindan writes:

"Viewed in this context, the choice of

words in the Bhagavad Gītā (4:13), guṇa-karma-vibhāgaśaḥ (based on modalities

and work) indicates a paradigm shift in a society stagnating because of

worldviews that categorized hereditary (kula/jāthi) work communities as noble

or defiled due to the imposition of values like ahimsa as universal. If the

text were casteist or pro-casteist, it could have unambiguously declared itself

as kula-janma-vibhāgaśaḥ (based on clan and birth)."

This

brings us to the end of the first part of this review, where Aravindan

deconstructs various myths and helps us reconstruct the Indic view of social

justice, grounded in the solid pillars of Indian spiritual and textual

tradition.

Conclusion

Reading

A Dharmic Social History of India a reconstructing of Indic narrative of

social justice has been an eye-opening journey. It challenged many

preconceived notions I had encountered in mainstream discourse, replacing them

with a deeper understanding of India’s organic social evolution. Aravindan’s

work made me realize that social justice in the Indian context was never about

radical revolutions but about silent transformations guided by spiritual

wisdom. The idea that Yajña

and Bhakti were

not just religious concepts but civilizational forces shaping social harmony

was particularly striking. The Mahābhārata’s

rejection of rigid classifications through stories like Dharmavyādha forced me

to rethink the simplistic narratives often imposed on India’s past. Most

importantly, the emphasis on guṇa

and karma over

birth as determinants of social identity reaffirmed the depth of Indian

philosophy. This book doesn’t just reconstruct history—it reconstructs

perspectives, urging us to view Indian society through its own lens rather than

borrowed ideological frameworks.

Thus as we have seen till now, how an

inherent and indigenous corrective mechanism for social vices—leading to

various silent "reforms" in India—has gradually taken place through

the subtle presence of saints and sages, leaving no scope for the disruptive

model of "revolutions." Next, in the second part of the book review,

we will explore the remaining sections of the book, where the author delineates

the historical trajectory of social reforms through dozens of examples, drawing

inspiration from the powerful metaphors of the Vedic Yajña and Bhakti

tradition.

Click here to read the second part of the review.

- 289 min read

- 22

- 2