- Visitor:43

- Published on: 2025-07-11 04:15 pm

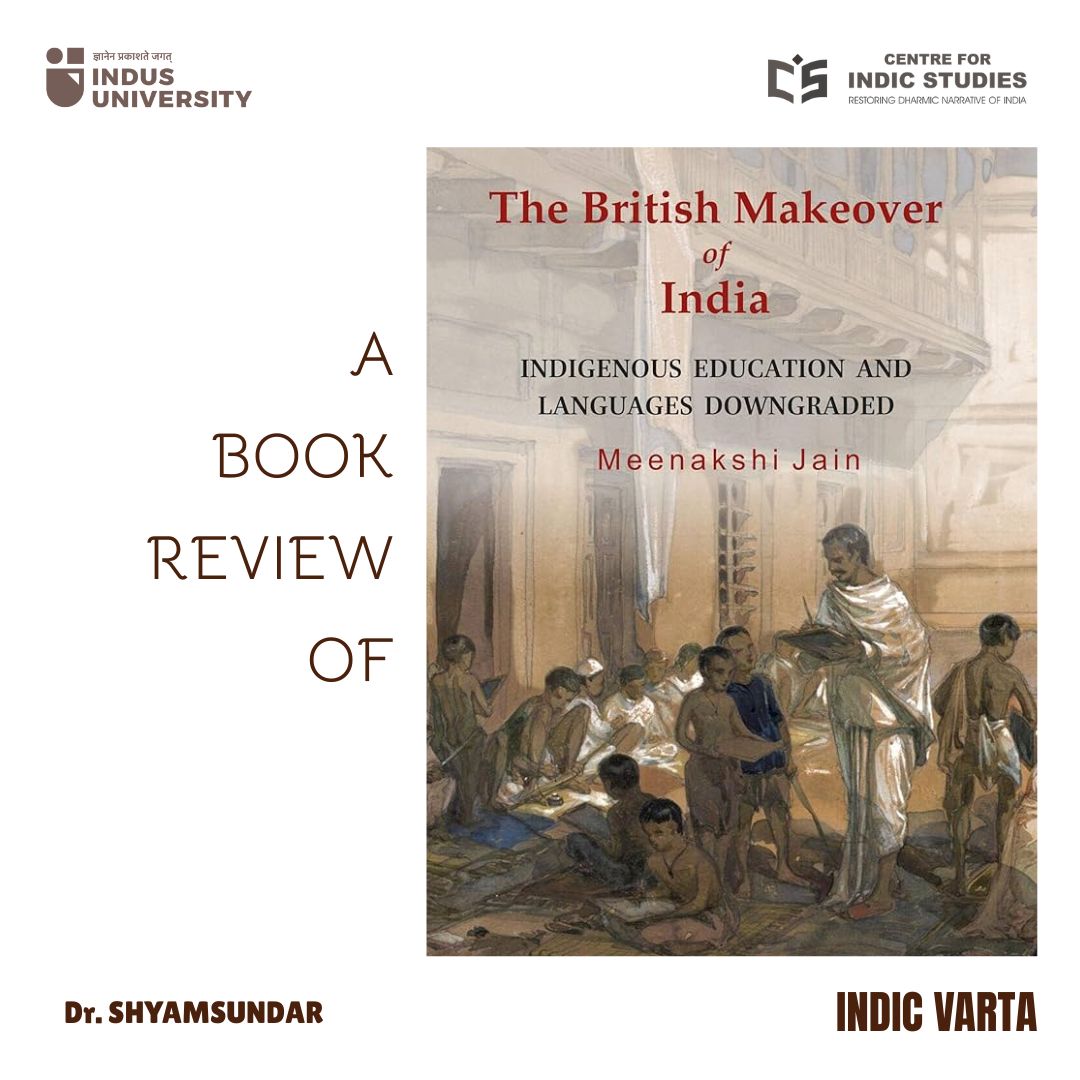

The British Makeover of India - Judicial and Other Indigenous Institutions Upturned

Meenakshi Jain’s The British Makeover of India: Judicial and Other Indigenous Institutions Upturned (Aryan Books, 2024) is a meticulously researched exploration of how British colonial policies dismantled India’s indigenous judicial and institutional frameworks. This work offers a compelling narrative of transformation, tracing the shift from early British admiration of Indian systems to their systematic replacement with Western models. Jain, an associate professor of history at Gargi College, University of Delhi, and a Padma Shri recipient (2020), brings her signature rigor to this volume, the first of a two-part series. This review analyzes the book chapter by chapter, assessing its arguments, evidence, and implications, while critically engaging with its perspective on colonial impact and indigenous resilience.

Early British View of Indian Civilization:

In the first chapter, Jain opens with a broad overview of her thesis: the British encounter with India began with intrigue and respect for its ancient institutions, only to evolve into a mission of overhaul driven by imperial ambition. She situates the book within the eighteenth-century context, when East India Company officials first documented India’s judicial and social systems as well as civilization. She has shown that the Englishmen found that Indian culture is “a deep and appealing wisdom.... (they) praised the institutions and material civilization of India... The early Company men found that Indian culture has always been “a living reservoir of ancient paganism and ancient wisdom” (p.1).

The chapter establishes the book’s scope focusing on judicial institutions and their upturning while hinting at the broader cultural and administrative shifts to be explored in the forthcoming second volume on education and languages. Further, she has shown that Sanskrit has a concise grammar that encompasses all its core principles. In this regard, she has quoted Dow’s quotation on Indian ancient language i.e. “Though the Shanscrita is amazingly copious, a very small grammar and vocabulary serve to illustrate the principles of the whole.

In a treatise of a few pages, the roots and primitives are all comprehended, and so uniform are the rules for derivations and inflections, that the etymon of every word is, with facility, at once investigated.” (P.6-7) Jain’s introduction is engaging, framing the narrative as a journey from admiration to disdain. She draws on early Company records to illustrate initial British impressions, setting up a contrast with later colonial attitudes. However, her reliance on a binary respect versus rejection might oversimplify the complex motivations of individual administrators, a point critic could probe further.

Early Advocates of the Need to Retain ‘Native’ Institutions

Chapter two delves into the accounts of early British officials who observed India’s indigenous institutions with a mix of curiosity and approval. As she has mentioned that “...in 1765, the Mughal Emperor conferred the Diwani rights (right to revenue collection and judicial responsibilities) of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa on the East India Company.” (p.10) Jain highlights the views of following figures like - Luke Scrafton, J.Z. Holwell, Alexander, William Bolts, Harry Verelst Warren Hastings, which they have advocated for the need to retain native institutions. Luke Scrafton observed that “Englishmen were no longer perceived as mere merchants, they were treated as umpires of Indostan.

Further, he mentioned the limited nature of “Tartar” conquest, the retention of vast tracts of land by Hindu rajas, and the continuance of ‘old Gentoo Laws’ which is significant parts of the subcontinent.” (p.10) Further, he advocates that Gentoo laws should be continued as it is a hereditary right to land enjoyed by all, even tenants. Further, Zephaniah Holwell highlighted the need to be aware of Gentoo religion and history. He stated that the East India Company gained rich financial status during that period. The East Indies and Bengal were so important an object and concern to Great Britain.

The data presents that the two provinces of Bengal and Bihar produced revenue of eleven khorore (Crore) per annum, or 13,750,000 pounds sterling. (p.12) Further, Alexander Dow highlighted that the Mughals did not interfere with the laws of the native systems during their rule in India, leaving indigenous laws largely untouched. He noted that while the Pathans and Mughals introduced many laws from northern Asia after conquering India, the core legal system mostly traced back to ancient regulations passed down by Brahma and his followers.

William Bolts (1740–1808), a Dutch adventurer who joined the Bengal civil service and later became an alderman in Calcutta, emphasized the East India Company's growth into a powerful entity and the need to preserve indigenous institutions, noting that the Mughals had allowed locals to retain their personal and civil laws based on Shastras. He highlighted that in non-capital or non-criminal cases, Hindus (Gentoos) were generally left to their Brahmins to decide matters according to their Shastras, despite limited knowledge of these ancient scriptures. Bolts also pointed out the distinct differences between Hindus and Muslims (Mahomedans), whose religious and legal systems were challenging to reconcile. (p.13)

Further, Warren Hastings, who saw value in India’s decentralized judicial systems, such as village panchayats. These officials noted the systems’ longevity and effectiveness, having survived centuries of “Tartar” (Mughal) rule with minimal state interference. The strength of this chapter lies in its primary source citations, which lend authenticity to Jain’s claim of initial reverence. She argues that these observations reflected a pragmatic approach, prioritizing governance efficiency over cultural imposition. Yet, the chapter could benefit from a deeper analysis of how these perceptions were shaped by Orientalist biases, which romanticized India’s past while ignoring its contemporary dynamism.

The Orientalists:

In chapter three, Jain shows that in the 18th century, British perspectives on Indian language and culture were shaped by a mix of curiosity, pragmatism, and colonial ambitions. Early British traders and officials, primarily from the East India Company, encountered a diverse and complex civilization. Their views ranged from admiration to condescension, often filtered through their own cultural lens and the practical needs of trade and governance. In case of language interest and study, Some British scholars, like Sir William Jones, were fascinated by Indian languages, particularly Sanskrit.

Jones founded the Asiatic Society in 1784 and his work on Sanskrit revealed its linguistic connections to European languages, sparking interest in comparative philology. Persian, as the administrative language of the Mughal Empire, was also studied for practical reasons, as it was key to engaging with Indian elites. Most British officials learned local languages like Hindustani (a blend of Hindi and Urdu) or regional languages to facilitate trade and administration. However, there was little effort to promote or preserve these languages; they were seen as tools, not cultural treasures. Cultural Superiority of Many Britons viewed Indian languages as "exotic" but inferior to European languages, particularly English, which they increasingly promoted as a marker of prestige and control by the late 18th century.

Jain also shows that early British accounts, like those of travelers and scholars, often expressed awe at India’s ancient civilization, art, architecture (e.g., the Taj Mahal), and philosophical traditions. Texts like the Upanishads and Mahabharata intrigued intellectuals, who saw parallels with classical Greek or Roman traditions.

The British often framed Indian culture through an "Orientalist" perspective, portraying it as static, mystical, or decadent. This justified their role as "civilizers" while allowing them to exoticize and study Indian traditions without fully respecting them. Many Britons, especially those outside scholarly circles, dismissed Indian customs, religions (Hinduism and Islam), and social structures (like the caste system) as backward or superstitious. Practices like sati were sensationalized to underscore perceived British moral superiority.

As the East India Company’s power grew, cultural engagement became subordinate to control. By the late 18th century, British policies began favoring Western education and Christian missionary activity, signalling a shift toward cultural imposition over appreciation.

The 18th century was a transitional period. Early in the century, the British were one of many players in India, competing with the French, Dutch, and Indian rulers. This fostered a more diplomatic engagement with Indian culture. After the Battle of Plassey (1757), as British dominance grew, attitudes hardened, and cultural superiority became more pronounced. Class differences among the British mattered. Scholars and administrators often had more nuanced views than soldiers or merchants, who were more likely to stereotype or exploit.

In summary, British views of Indian language and culture in the 18th century were a mix of fascination, utility, and growing disdain, shaped by intellectual curiosity, colonial goals, and cultural biases. While some Britons engaged deeply with India’s heritage, most saw it as inferior to their own, setting the stage for more aggressive cultural interventions in the 19th century.

Disastrous Early Administrative Ventures of the Company:

In the fourth chapter, Meenakshi Jain examines the East India Company’s initial attempts to establish administrative control in India during the late 18th to early 19th centuries, focusing on the failures and disruptions caused by these efforts. Drawing on Jain’s methodology is known for meticulous research and reliance on primary sources. The chapter probably critiques the company’s imposition of foreign administrative systems that clashed with indigenous institutions, leading to social, judicial, and economic upheaval. The chapter likely begins by setting the stage for the East India Company’s transition from a trading entity to a governing authority, particularly after the Battle of Plassey (1757) and the grant of Diwani rights in Bengal (1765). These events gave the Company revenue and administrative responsibilities, but its lack of experience in governance led to mismanagement.

Jain probably highlights how the company’s early administrative ventures ignored or dismantled well-functioning Indian judicial and social institutions. As noted in reviews, the book discusses how indigenous systems delivered “inexpensive and quick justice” before British intervention. The chapter may detail specific examples, such as the replacement of local panchayats or qazi courts with British-style revenue and judicial systems, which were alien to the population.

The title “Disastrous” suggests a focus on the negative consequences of these policies. The chapter likely explores how the Company’s revenue policies, such as the Permanent Settlement of 1793 in Bengal, disrupted agrarian economies, overburdened peasants, and enriched a new class of zamindars, leading to widespread distress. Jain may also discuss famines, such as the Bengal Famine of 1770, as a direct result of administrative mismanagement. Consistent with Jain’s argument that British interest in Indian systems was “instrumental” and aimed at governance rather than cultural engagement, the chapter probably critiques the Company’s superficial understanding of Indian customs.

Early administrators, influenced by Orientalists or evangelicals, may have misjudged or manipulated local practices, leading to resistance or administrative failures. Chapter 4 marks a pivotal shift, detailing the mid-nineteenth-century change in British attitudes. Jain attributes this to military successes such as the defeat of Napoleon in 1815 and growing imperial confidence, which fueled a belief in European superiority. The earlier policy of non-interference gave way to reformist zeal, setting the stage for institutional overhaul.

This chapter excels in connecting global events to local policy shifts, offering a macro-historical lens. Jain’s argument is clear: power altered perceptions, turning admiration into disdain. Yet, she might overemphasize external triumphs, underplaying internal factors like evangelical pressure or economic motives, which later chapters address more fully.

British Crafted ‘Indigenous’ Texts

Chapter five examines the British colonial efforts to codify and reinterpret Indian legal and cultural systems, particularly Hindu law, to align with their administrative and ideological goals. The chapter highlights how the British, under figures like Warren Hastings, sought to create a unified legal framework by commissioning texts like the Vivadernavasetu (A Code of Gentoo Laws), compiled by 11 pundits. This code drew heavily from the Dharmashastras, which the British mistakenly assumed were the sole authoritative texts for Hindu law, ignoring the diversity of customary and local practices that often superseded scriptural dictates.

Jain argues that this approach led to significant errors, as the British imposed a rigid, text-based legal system that did not reflect the fluid and community-driven nature of indigenous judicial practices. The chapter details how colonial administrators, driven by a mix of Orientalist fascination and a desire for efficient governance, overlooked the practical realities of Indian society, where local traditions often held more sway than canonical texts. This misstep was compounded by the British tendency to view Indian society through the lens of the varna system, force-fitting diverse jatis (endogamous social groups) into a simplified fourfold structure, further distorting social realities.

The chapter underscores the broader colonial agenda of reshaping Indian institutions to serve imperial interests, often under the guise of preserving “indigenous” systems. By prioritizing textual authority over lived practice, the British not only misunderstood Indian legal traditions but also laid the groundwork for a hybrid system that was more Anglo-Saxon in structure than authentically Indian, setting a precedent for further cultural and institutional interventions.

Headlong on the Perilous Path

Chapter Six focuses on the British attempt to create a standardized Hindu legal code during the late 18th century, particularly under the governance of Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General of Bengal. Jain details how the British, initially respectful of India’s decentralized and customary judicial systems, began to impose their own interpretations of Hindu law to streamline colonial administration.

This shift, as the chapter’s title suggests, set India on a “perilous path” towards cultural and institutional disruption, driven by a mix of administrative convenience, racial biases, and evangelical influences. The chapter examines the creation of the Vivadernavasetu (translated as “A Code of Gentoo Laws”), a British-mediated compilation of Hindu legal principles drawn from the Dharmashastras. Commissioned by Hastings in 1772, this project involved 11 pundits tasked with codifying Hindu law. However, Jain argues that this endeavor was flawed from the outset, as it prioritized canonical texts over local customary practices, leading to misinterpretations and a disconnect from the lived realities of Indian society.

The chapter situates this development within the broader transition from the East India Company’s early reverence for indigenous systems to a more aggressive imposition of British legal norms by the mid-19th century. Further, Jain’s analysis of this chapter revolves around several interconnected themes:

1. Misguided Codification Efforts: The British, unfamiliar with the fluidity and diversity of Hindu legal traditions, assumed that a single, text-based code could govern all Hindus. Jain highlights how the Vivadernavasetu was based on the Dharmashastras, which were normative texts rather than universally applied laws. In practice, local customs and traditions often superseded these texts, varying across regions, communities, and castes. By privileging scriptural authority, the British “committed grievous errors” in their attempt to implement what they believed were native laws, undermining the organic, community-driven judicial systems that had functioned effectively for centuries.

2. Colonial Power Dynamics: The chapter underscores how the codification project was less about preserving Indian traditions and more about facilitating colonial governance. The British needed a simplified legal framework to administer justice, collect revenue, and maintain control over a diverse population. Jain argues that this instrumental approach reflected a growing sense of European superiority, as the British began to view indigenous systems as inferior and in need of reform. This shift marked a departure from the earlier observations of Company officials who admired the resilience of India’s judicial institutions despite centuries of “Tartar” (Mughal) rule.

3. Cultural Misrepresentation: Jain critiques the British for force-fitting Indian social structures into rigid frameworks, such as the varna system, which they misunderstood as a monolithic caste hierarchy. The chapter notes that the Vivadernavasetu and subsequent legal interventions ignored the complexity of jatis (endogamous social groups) and their localized practices. This misrepresentation not only distorted Hindu law but also sowed seeds of social division, as colonial policies began to ossify the fluid social categories into fixed identities, a legacy that persists in modern India.

4. Seeds of a Perilous Path: The chapter’s title encapsulates Jain’s argument that the codification of Hindu law was a turning point that set India on a trajectory of cultural alienation. By prioritizing written texts over oral traditions and customary practices, the British laid the groundwork for further interventions, such as the imposition of English education and Christian missionary activities, which are explored in later chapters of the book. The “perilous path” refers to the erosion of indigenous pride and self-governance, as colonial policies created a class of Indians disconnected from their cultural heritage.

Judicial System - Pre-1772

In chapter seven, Jain shows that the East India Company was responsible for delivering justice and collecting revenue of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa till 1765. At the same time, the Mughal judicial system prevailed which was based on Islamic institutions. Jain reconstructs the pre-colonial judicial landscape before the British assumed diwani (revenue rights) in 1772. She describes a decentralized system where local bodies, panchayats, caste councils, and qazis handled disputes efficiently, often beyond Mughal oversight.

Further, she describes prior to 1726, judicial decisions of the Courts of Justice were very odd. Further she cited that, on 5 July, 1724, in Bombay, a woman named Bastook was accused of “diabolical practices” for ignorantly mixing rice in rituals to heal the sick. She received eleven lashes at the church door and, with others guilty of similar acts, had to do penance in church. The company’s courts were thought to execute only for piracy, but men were hanged as pirates for unrelated crimes. In addition, Jain has shown that The Mayor’s Courts in Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay, established in 1726, failed to deliver fair justice and continued English laws until 1774. The pre-1772 Mayor’s Courts in Bengal, staffed by British Company employees lacking legal skills, delivered arbitrary justice for decades. Conflicts with the President and Council worsened outcomes, especially as Company rule grew, subjecting native Bengalis to unfamiliar laws and harsh punishments.

In 1765, Bengalis petitioned Fort William’s leaders to pardon Radachurn Mettre, convicted of forgery, highlighting their distress over the English imposing foreign laws while ignoring local ones, causing unfair suffering. Further, she shows that the 1753 Charter of George II permitted natives in Company territories to settle disputes via the Mayor’s Court but excluded them from its jurisdiction, though there is no proof of native exemption.

After gaining the Diwani of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa in 1765, the East India Company managed civil justice but, lacking expertise, left judicial roles to natives from 1765 to 1772, preserving the Mughal Islamic justice system. Bengal’s criminal justice favoured Muslims, imposing stricter rules on non-Muslims, slaves, and women, requiring two witnesses for their cases, and allowing kin to pardon murderers or settle with compensation, often using punishments like mutilation.

Further, the author shows Muhammad Reza Khan’s views regarding justice, who was appointed Naib Diwan by the East India Company in 1765, stated that Islamic laws had governed since Muslim rule, excluding Hindus from such matters. On May 4, 1772, he wrote that Quranic law guided civil and criminal courts. He noted Brahmins never handled Muslim disputes in Islamic governance. Khan saw Hindus as subjects under Islam, arguing it would be inconsistent for a Brahmin to issue orders against a Muslim Emperor’s faith in justice matters.

Hindus could accept court rulings if they brought disputes, but cases they initiated needed a magistrate trained in Islamic law for more accurate decisions than Brahmins or tribal leaders. Moreover, she has shown that what kind of views were expressed in Hedaya- The Hedaya, translated by Warren Hastings, notes that Mohammedan Law governs criminal and much of civil law in India, necessitating that those ensuring justice understand Mussulman court principles, especially since many under British rule are Mohammedans whose adherence to these laws impacts the empire’s prosperity. Unlike Zimmess, who are fully subject to Mussulman law in temporal matters as native subjects, Hanefa argues they are not bound by Islamic religious practices (like fasting or prayer) or related temporal acts, though these may be legally valid, as they are granted freedom.

This chapter reinforces her thesis that indigenous institutions were robust until disrupted. The historical detail here is impressive, painting a vivid picture of pre-British justice.

Company Judicial System takes Shape

Chapter eight traces the gradual imposition of British legal structures, particularly after the 1857 uprising solidified Crown rule. Jain critiques the introduction of courts, codes, and adversarial processes, arguing they alienated Indians accustomed to conciliatory justice. She links this shift to a broader civilizing mission. Jain’s argument is compelling, supported by examples of prolonged litigation and rising costs under the new system. Yet, her nostalgia for indigenous methods might overlook their adaptability; some panchayats persisted alongside British courts, suggesting a hybridity she mentions only briefly.

The Cornwallis System

In chapter nine, Jain introduces the role of evangelical missionaries in pushing judicial reform. She contends that their zeal to “civilize” India amplified racial biases, framing indigenous systems as barbaric. This chapter ties religious ideology to legal policy, a crucial dimension of colonial transformation. The linkage of evangelism to judicial change is well-documented, drawing on missionary writings and parliamentary debates. Jain’s focus on external imposition, however, might downplay internal reformist voices, Hindu and Muslim elites who occasionally supported modernization, complicating her narrative of unilateral disruption.

Critics of the Cornwallis System

In chapter ten, Jain examines the British-introduced darogah (police) system as an instrument of control, replacing community-based enforcement. She argues that this centralized force eroded local autonomy, often serving colonial interests over public welfare. This chapter’s strength lies in its granular detail reports of darogah corruption and inefficiency abound. Jain effectively ties this to judicial overhaul, showing how policing and justice intertwined. A comparative look at pre-colonial enforcement, though, could clarify the extent of change versus continuity.

Support for the Indigenous Judicial Institutions continues

Chapter eleven, Building on earlier chapters, Jain critiques the codification of laws under figures like Thomas Macaulay. She argues that the Indian Penal Code, 1860 and other statutes ignored customary nuances, imposing a uniform system ill-suited to India’s diversity. Her evidence, legal texts and Indian petitions underscores the disconnect. Jain’s critique is sharp, but she might overstate codification’s novelty; Mughal rulers also standardized some laws, suggesting a longer history of legal consolidation she could address.

Advocacy of Indian Employment and the Reality

Chapter twelve laments the marginalization of panchayats, once central to rural justice. Jain blames British policies, taxation, centralization, and judicial supremacy for their decline, viewing it as a loss of grassroots governance. Jain’s passion for indigenous systems shines here, supported by colonial surveys lamenting panchayat erosion. Yet, her idealization risks romanticizing these bodies; some were caste-bound or patriarchal, flaws she acknowledges but doesn’t fully unpack.

Indigenous Institutions of Justice - Panchayats

In chapter thirteen, Jain revisits the panchayat system in depth, portraying it as a flexible, community-driven model. She contrasts its restorative approach with the punitive British system, arguing for its cultural fit. This chapter reiterates earlier points with added case studies, reinforcing her thesis. Its repetitive nature, however, suggests a need for tighter editing, new insights into urban justice or regional variations could enrich the discussion.

The chapter is strategically positioned after discussions of pre-colonial judicial systems and the British-mediated Hindu code, providing a natural progression into the colonial imposition of new administrative tools like the darogah system. It is well-organized, divided into clear sections that trace the origins, implementation, and consequences of the darogah system, supported by primary sources and historical accounts. The chapter begins by contextualizing the pre-British law enforcement framework, particularly the role of village-based systems like the panchayat, which delivered localized, accessible justice. It then transitions into the British introduction of the darogah, a centralized police official, as a mechanism to consolidate control. Jain methodically details the operational mechanics of the darogah system, its divergence from indigenous practices, and its long-term impact on Indian society.

The chapter concludes with a critical reflection on how this system contributed to the erosion of community autonomy and the imposition of a foreign administrative ethos.

Darogah - An instrument of British Control

In chapter fourteen, Jain’s central argument in this chapter is that the darogah system was not merely a reform of law enforcement but a deliberate instrument of British control, designed to undermine indigenous institutions and centralize authority. She highlights several key points:

1. Disruption of Indigenous Systems: Prior to British intervention, justice and law enforcement in India were community-driven, with panchayats and local leaders resolving disputes efficiently and inexpensively. Jain cites early East India Company officials, such as Luke Crafton and John Holwell, who noted the effectiveness of these systems despite centuries of non-interference from medieval states. The introduction of the darogah, a salaried official appointed by the British, shifted authority away from communities to colonial administrators, disrupting this decentralized model.

2. Centralization and Control: The darogah system, formalized in the early 19th century, was a cornerstone of British efforts to impose a uniform administrative structure. Jain argues that darogahs, often drawn from local elites but loyal to British authorities, served as intermediaries who enforced colonial policies, collected intelligence, and suppressed dissent. This system enabled the British to penetrate rural areas, where indigenous institutions had previously held sway, thereby extending their political and economic dominance.

3. Cultural and Social Impact: Jain underscores the cultural alienation fostered by the darogah system. Unlike traditional systems rooted in local customs, the darogah operated under British legal codes, which were often incomprehensible to the populace. This disconnect eroded trust in justice delivery and created a perception of foreign imposition. The chapter also notes how the darogah’s role in tax collection and surveillance further strained relations between communities and the colonial state.

4. Long-Term Consequences: The chapter compellingly links the darogah system to the broader colonial legacy, arguing that it laid the groundwork for modern policing in India, which retained its centralized and coercive character post-independence. Jain critiques the system’s inefficiency, citing ground reports that highlighted corruption and mismanagement, which contrasted sharply with the swift justice of pre-colonial systems.

The chapter’s strengths lie in its meticulous research and balanced narrative. Jain draws on a wealth of primary sources, including East India Company records and contemporary accounts, to substantiate her claims. Her use of quotes from figures like H.H. Wilson, who criticized the cultural assault on native institutions, adds depth to her argument about the deliberate nature of British policies. The chapter is accessible yet scholarly, making it suitable for both academic readers and those with a general interest in colonial history.

Jain’s ability to connect the darogah system to broader themes of colonial governance such as evangelical influences and the Anglicization of Indian society which enhances the chapter’s relevance within the book. Her critical examination of the establishment narrative avoids ideological speculation, focusing instead on evidence-based analysis, which aligns with her reputation as a historian untainted by bias.

While the chapter is robust, it has minor limitations. First, the discussion of the darogah’s role could benefit from more detailed case studies or regional examples to illustrate variations in implementation across India. For instance, how did the system function differently in Bengal versus Punjab? Such specificity could strengthen the argument about its widespread impact. Second, while Jain critiques the system’s inefficiencies, she could further explore the perspectives of Indian subordinates within the darogah framework to provide a more nuanced view of collaboration and resistance. Additionally, the chapter assumes a certain level of familiarity with colonial administrative terms, which might pose a slight barrier for readers new to the subject. A brief glossary or explanatory notes could enhance accessibility without compromising scholarly rigor.

Confusion worse confounded:

In chapter seventeenth, Jain reflects on the enduring impact—India’s modern judiciary retains British DNA, with delays and inaccessibility echoing colonial flaws. She sees this as a tragic inheritance, urging a reappraisal of indigenous models. This chapter ties the book together, offering a poignant critique of postcolonial continuity. Jain’s call for revival is thought-provoking, though practical challenges, modern scalability and legal uniformity have remained underexplored.

Growing Inroads of Missionaries

In chapter eighteenth, Jain briefly compares India’s experience with other colonies, noting parallels in judicial imposition but emphasizing India’s unique pre-colonial sophistication. This widens her argument’s scope. The comparative approach is a welcome addition, though its brevity limits depth. More examples—say, Africa or Southeast Asia could sharpen her claims of British exceptionalism in India.

Rule of Strangers

In chapter nineteenth, Jain concludes by reiterating her thesis: the British makeover upturned effective institutions, leaving a legacy of alienation. She advocates revisiting indigenous wisdom, framing her work as a corrective to colonial historiography. The conclusion is forceful, blending scholarship with advocacy. While inspiring, its idealism might clash with pragmatic realities, a tension Jain leaves unresolved. Jain’s book is a De-tour force of historical revisionism, challenging narratives of British benevolence. Her evidence, archival records, legal texts, and contemporary accounts are robust, and her prose is accessible yet scholarly. She excels at exposing colonial hubris and its long-term costs, particularly in judicial alienation still felt today. However, her romanticization of indigenous systems occasionally borders on nostalgia, underplaying their flaws or adaptability. The narrative’s focus on British agency sometimes sidelines Indian responses, resistance, collaboration, or reform which could balance her account. Structurally, some repetition across chapters suggests room for consolidation. The British Makeover of India is essential reading for historians, legal scholars, and anyone interested in colonial legacies. It reframes India’s judicial past, urging a critical look at inherited systems. While not without flaws, its depth and conviction make it a standout contribution, eagerly anticipating its companion volume on education. Highly recommended for those seeking to understand the roots of modern India’s institutional challenges!

The book has more than 18 pages of references which is very robust and showcases the apt and wondrous readings of the author.

- 21 min read

- 0

- 0