- Visitor:30

- Published on:

Śri Rāma: Beyond Indology, History and Social Justice

Rāma surrounds, teaches, protects and pervades the entire life of a Hindu and at the end of his life its RāmaNāma that liberates him. So for a Hindu, Rāma is a very much a living reality, his God.

Millions of Hindus begin and end their day with the name Rāma. Rāma surrounds, teaches, protects and pervades the entire life of a Hindu and at the end of his life its RāmaNāma that liberates him. So for a Hindu, Rāma is a very much a living reality, his God. Throughout Bhārata you will find Hindus naming their sons after Rāma, girls praying for a husband like Rāma, the deep bonding between brothers being compared with that of Rāma and His brothers. If you ask a karasevaka, what made him undertake such a risky undertaking, you will find his answer based on the concept of ŚrīRāma being Bhagavān Himself and His sacred birthplace had to be reclaimed at any cost. But this obvious thing is obvious to everyone except academics for whom Rāma is an abstract idea, who was first only a mythological or historical human king, not even a moral ideal who later “became” a god. Unfortunately most of the intellectual discourse around Rāma today revolves around historicizing or psychoanalysing His character using a post structuralist framework in the name of academic or creative liberty while traditional understanding takes a backseat. The spiritual but not religious breed of Hindus cannot become more indifferent to it. The article here will not defend the tradition rather will present its incompatibility with the indologist’s and other modernist version of Rāma sanitized of all divinity.

When indologists of the past encountered the Hindu practices and Hindu texts they failed to make any sense out of it due to the lack of an underlying framework that was common in Abrahamic religions. Many indologists were also agents of the church with open evangelical goals. Camil Bulcke, who was a significant scholar especially on Rāmāyaṇa was a missionary himself. So it is understandable that the gaze of the indologist’s were necessarily a Christian gaze. Taking the white man’s burden on themselves the indologist now wanted to free the texts from the stakeholder’s of the text and teach the “true” meaning of the texts. However it will be a mistake to limit the misconception about Rāma to Christianity alone for the modern understanding, that is essentially atheistic and which to which the larger chunk of academics and popular writers today belong, also being diametrically opposite to Dhārmika understanding continues the legacy of early indologists with even more zeal and efficiency.

The incompatibilities are due to three radical differences between a Hindu’s and an academic’s approach. The first one is the difference in Pramāṇas. The second one is the lack of concepts like Puranjanma, Karma and Avatāravāda in the later approach. The third one is the conception of time which is cyclical for a Hindu and linear for the academic.

Pramāṇa means valid means of knowledge. They can broadly be classified into Pratyakṣa (perception), Anumāna (inference), Śabda (Vedas), Upamāna (comparison), Arthapatti (postulation) and Anupalabdhi (non-apprehension) Pramāṇa. The early indologists and modern academics alike, consider only Pratyakṣa and Upamāna and don’t take Śabda into account. Interestingly though early indologists had religious motive, but the framework they used was atheistic. Karapātra Swāmī argues in His ‘Rāmāyaṇa Mīmāṁsā’ that the existence of something can only be refuted by that pramāṇa, from which it can be confirmed just like the existence of an object of vision can only be confirmed or refuted by eye and not by any other organs. Dharma and Mokṣa, essentially being the subject of Śāstras i.e.; Śabda, cannot be refuted from pratyakṣa or anumāna pramāṇa.

The Hindu rationale for something happened is inherently based on the concept of karma and punarjanma. The academic cannot see anything beyond this life and this world either due to operating in an Abrahamic or atheistic framework. For a Hindu this is but one among infinite births operating in a cycle and so is this world. Without the notion of karma and punarjanma the academic reads exploitation and oppression everywhere. Same goes for avatāravāda as well. The idea of avatāra cannot be accommodated into any mode of inquiry other than the traditional one.

In Hindu idea of time there are four yugas: Satya, Tretayā, Dvāpara and Kali and after the completion of one caturyuga (a cycle from Satya to Kali) it again starts from Satyayuga. A kalpa includes thousand such caturyugas. In each Kalpa the Lord takes avatāra several times. Each time the happenings doesn’t remain exactly the same. This results in difference in texts. That is why when an event described in two text varies, tradition accommodates both by the concept of KalpaBheda instead of declaring interpolation. Modern academic on the other hand, with his biblical conception of linear time fails to resolve such nuanced issues.

Due to the limitations discussed above it can never accommodate the idea of ŚrīRāma being Bhagavān Himself. Infact it can never produce an idea that doesn’t contradict the idea of God in the end. As per the academically accepted theory, the “original” Hinduism was a pagan religion. Early pagans, out of fear, worshipped nature. Air, water, fire, thunder etc were considered divine by them. Thus in the “original” Hindu text RigVeda there is only hymns for gods like Indra, Vāyu, Agni etc. Now inside ṛgveda itself there are sections which have Mantras mentioning Viṣṇu or Devī or Rudra. “Then those must have been written later and added to the original text” claims the academic. In fact one can produce pages after pages of reference from any text, that doesn’t agree with the academic’s opinion but the academic can still vanish them into thin air by the simple incantation of “interpolation” and “later addition”.

Seen in the above light the ontological atheistic bias in the academic interpretation becomes clear. For an academic any given religious text is a mere fiction, some fiction predates others and the most primitive fiction is the “original” version. The academic pretends truth and value neutrality that is, he claims to not pass a verdict on whether the text is true or false or good or bad. Prof. A. K. Saran bluntly remarks ,”So what modern sociologists do is to work on the implicit assumption that these beliefs are false, and so long as this assumption, though implicit, is generally shared among the social scientists, the show of value- and truth- neutrality can smoothly go on.” (Though he mentions sociology specifically here, I trust it stands true for our present discussion too.)

Following this pattern for an academic, Rāmayaṇa becomes a popular fiction written probably in some century BC. Earlier it was the story of a king which received popularity. In the Vedas there was no idea of bhakti. Later to resist the Buddhists and strengthen their grip on the society, wily Brahmins made Rāma a popular hero and with the emergence of Bhakti, Rāma became the 7th Avatāra of Viṣṇu, a God. A post structuralist psychoanalysis of Rāma shows the exploitation women and śudras used to face in ancient Hindu society which becomes clear from Sītā’s Agni Parīkṣā or Śambūka vadha. Also as it was a mere fiction, multiple author expressed their creative liberty and wrote their own versions, which is why we have so many versions of Rāmāyaṇa. To counter all this, unfortunately the home team has fallen for the trope to prove Rāma as a historical figure.

Itihāsa on the other hand is not a random collection of mere “facts” but as the Viṣṇudharmottara Purāṇa says:

धर्मार्थकाममोक्षाणां उपदेश समन्वितम्।

पूर्ववृत्तं कथायुक्तं इतिहास प्रचक्ष्यते॥

“The account of past which advices a man on how to attain the 4 puruṣārthas, is called itihāsa.”As we have discussed tradition accepts Vedas as Śabda pramāṇa. Though along with academics, Arya Samajis and pop advaitins don’t agree, tradition includes smṛtis, purāṇas and itihāsas as pramāṇa which are seen as extended commentary on aphorical Veda mantras that expounds the teaching through prescriptions and examples.

इतिहास पुराणाभ्यां वेदं समुपबृहंयेत् (महाभारत 1/1/267)

Traditionally some section of Vedas are not written later hence are less authentic

comparatively. They are eternal and without any author. The myriads of different Rāma kathās doesn’t bother a Hindu. Millions of Hindu chant everyday in the Rāmarakṣā Stotra:

चरितं रघुनाथस्य शतकोटि प्रविस्तरम्।

(There are hundreds of crores of ways in which Śrī Raghunātha’s avatāra has happened in different kalpas.) This should not be confused with an encouragement to ‘everything goes’ principle. In all the available Rāmāyaṇas, Rāma is Śrī Viṣṇu Himself, is the Vigrahavān Dharma (Dharma personified) and the ideal king, son, brother and husband. A Hindu doesn’t judge ŚrīRāma’s conduct from an anthropocentric modern point of view rather all ideas of righteousness are tasted against Rāma’s standard for him. As long as this is maintained Hindus have actively encouraged all such devotional works. Also the questions raised by social justice warriors and feminists are nothing new. Sāmpradāyika Ācāryas have taken notice of even the movement of an eyebrow in the text and explained it in detail. But due to the inherent differences and atheistic presupposition of the academic such explanations are always kept aside.

To conclude we restate what we have stated at the beginning of this essay. To a Hindu ŚrīRāma is his God, first and foremost. His unparalleled compassion, glory and grandeur cannot be sung by even gods.

आरामः कल्पवृक्षाणां विरामः सकलापदाम्।

अभिरामः त्रिलोकानां रामः श्रीमान् स नः प्रभु:॥

(श्रीरामरक्षास्तोत्र)

Who is the garden of KalpaDrumas (wish fulfilling trees), the end to all adversities and the delight of all three worlds, that Śrīmān Rāma is our Lord.

A beautiful verse comes in the Bālakāṇḍa of ŚrīRāmacaritaMānasa which states the purpose of Avatāra, after quoting which we will offer the essay at ŚrīRāma’s lotus feet .

“ब्यापक अकल अनीह अज निर्गुन नाम न रूप।

भगत हेतु नाना बिधि करत चरित्र अनुप॥

“The Lord, who is all pervading, indivisible, desireless, unbegotten, attributeless and without any Name or form; performed various marvellous acts for the sake of His devotees.”

||Śrīrāmārpaṇamastu||

References:

1. रामायण मीमांसा by HH Hariharananda Saraswati Karapātra Swāmī

2. Mostly ślokas and dohas have been taken from Gita press editions of the texts.

3. A.K.Saran, Hinduism in Contemporary India

4. I am particularly grateful to Śrī Halley Kalyan, for his brilliant introduction to Karapātrī ji Maharaj’s book.

https://youtu.be/N8xqbRCaQXc

Also engaging with him in social media has been helpful to improve my understanding of tradition

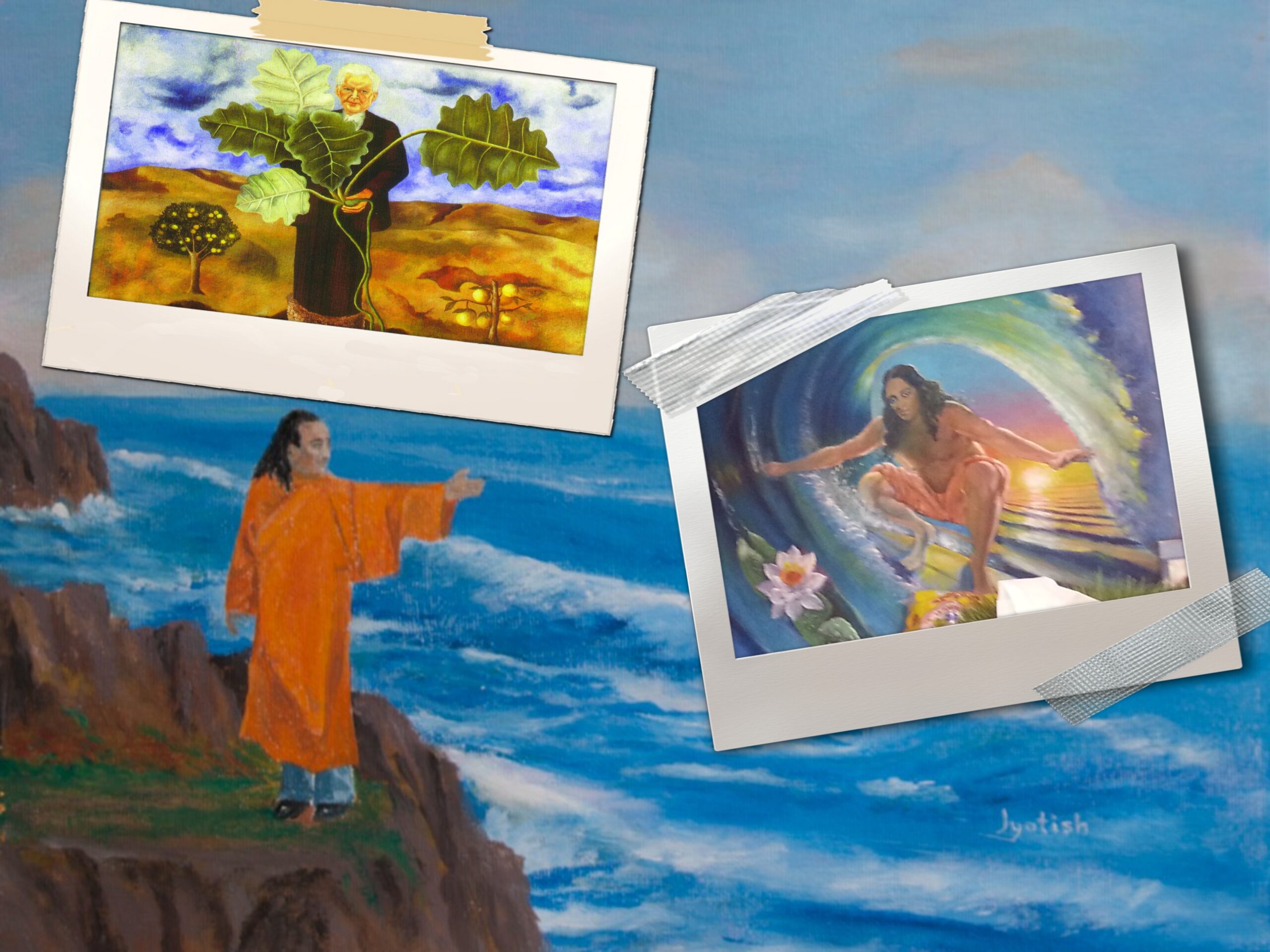

Art work by Zai Ji

Center for Indic Studies is now on Telegram. For regular updates on Indic Varta, Indic Talks and Indic Courses at CIS, please subscribe to our telegram channel !

- 15 min read

- 0

- 0