- Visitor:128

- Published on: 2024-10-04

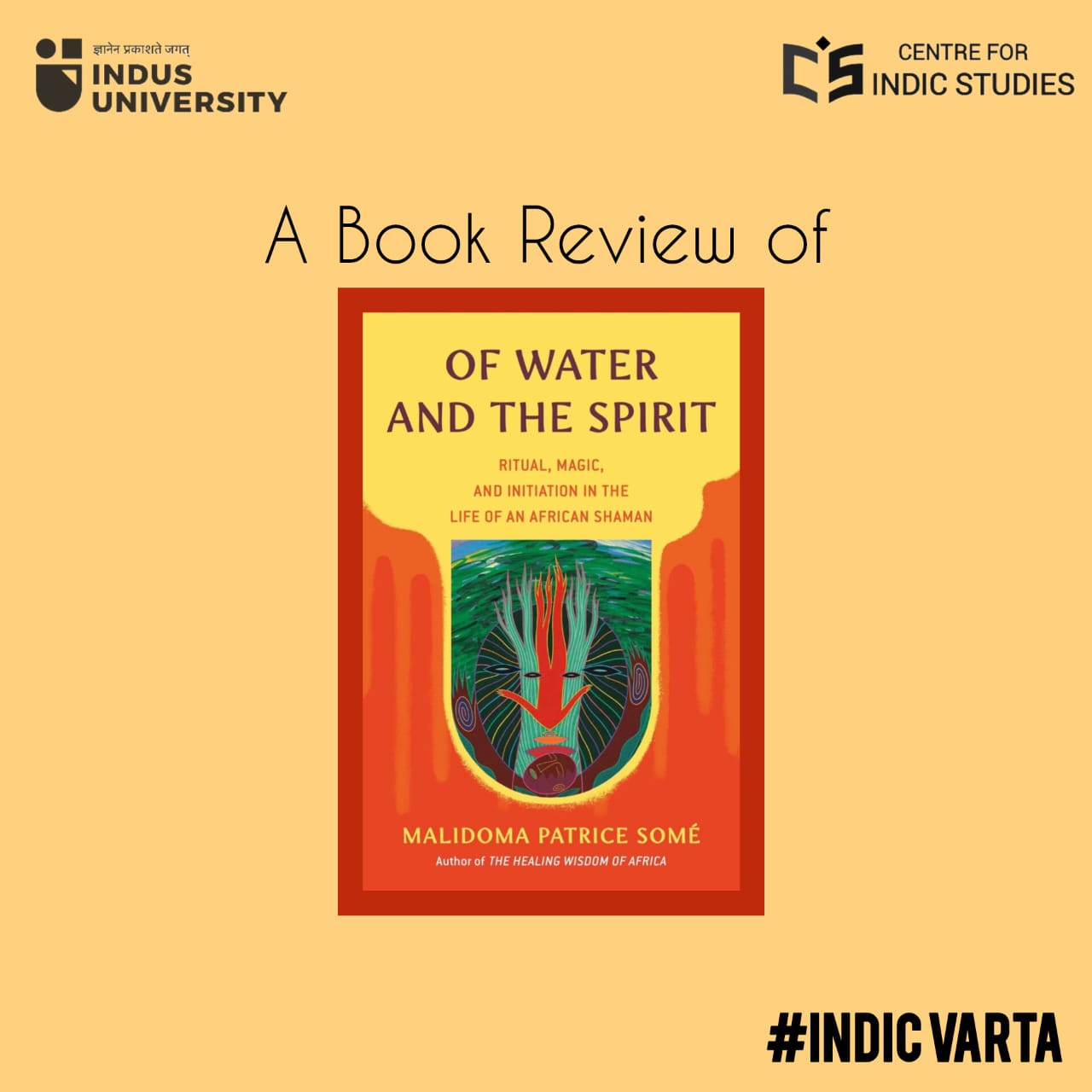

Of Water and the Spirit: Ritual, Magic, and Initiation in the Life of an African Shaman

''West is as endangered as the indigenous cultures it has decimated in the name of colonialism." — Malidoma P. Some

About the Author

The autobiographical account of Malidoma P. Some tells us one fascinating story that navigates through the colonial experience (territorial and otherwise) of the small town of Dagara in the French occupied Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso), shining light on the after effects of the foreign occupation including the cultural disruption and religious colonialism in the African sub-continent in the later part of twentieth century by writing as a first hand witness. Some's narrative is particularly insightful and groundbreaking in its narration about the life and experiences of an indigenous healer. He travels far beyond the cliche of challenging narrative of the white man's burden and then some more. The book unfolds with the journey of Malidoma, from a sweet innocent child who was believed to be the reincarnated spirit of an ancestor by elders of the tribe to becoming Patrice who was abducted and trained by the French Jesuits to be an addition to the 'native' missionary force, and then to becoming Malidoma Patrice Some, a Western-educated shaman with three Master’s Degrees and two PhDs. The story of Some personifies the story of Christian occupation of African culture and the redeeming journey of an aspiring priest to an initiated Shaman portraying the resilience of tradition in the face of oppression.

Introduction

The book offers a window into the daily life and cultural practices of indigenous Dagara tribe of Burkina Faso to which the author belongs, the Dagara's do not differentiate between the natural and the supernatural, the author goes on narrating the beliefs and the traditional practices of Dagara's, their ancestral wisdom as well as their connection to the spirit world which he had witnessed as a four year old from the eyes of his grandfather who was the patriarch and a respectable elder in his tribe. The book tells two stories of a carefully interwoven account of authors initiation into the two contradictory lives of tradition and "fashionable'' modernity which can be seen in the steady erosion of the indigenous culture by forceful imposition of the French catholic values and language on the indigenous people.

It explores the post-colonial experience of Burkina Faso (on the life Dagara tribals in particular) which author makes us see through the eyes of Malidoma, a four year old child born witnessing the transcendental practices of Dagara's, their belief in the supernatural (which the Dagara believes' their ancestors guiding them in spirit) and the skepticism and valour of village elders in preserving their way of life against skirmishes of the white man. A change came into the life of Malidoma with a sudden death of his beloved grandfather which rushes too many uninvited changes into his life and sets his life on the trajectory that his grandfather fore predicted while naming him that, Malidoma - one who be friends a stranger/enemy.

The Stranger/Enemy

''... as soon as one culture begins to talk about preservation, it means that it has already turned the other culture into an endangered species."

Malidoma's family becomes a microcosm and can be seen as a subtle representation of working of the corrosive colonial influence on the colonies with passage of time. The three men of Bakhye's family, more correctly, the three generations of Bakhye's household which includes his grandfather (Bakhye), his father and the author himself are, in a manner, vivid personifications of the generational effect of colonialism on the colonised.

Malidoma was forcefully abducted by a French jesuit who posed himself as a friend and well wisher of his family and his father in particular and was thusly welcomed in the home of Bakhye by him immediately following the death of Bakhye (who was rightly suspicious of the priests intentions from the beginning). Malidoma's father was convinced by the priest in adopting the 'superior' ways of the Catholic Church and abandoning his cultural identity and 'superstitions' of his ancestors. Under his influence Malidoma's father decided to raise his children Catholic and make them learn the ways of their colonisers which he evidently admired at first but realised later, perhaps too late.

Malidoma's journey through the seminary is marked by internal conflict and rebellion against the oppressive system comprising his primary training in Rhetoric, to defend Christianity in the face of any contradiction (in order to be recruited to the 'native' missionary force) all the way to his quarrel with his vocabulary teacher as a result of upheaving religious consciousness. He discovers a sense of freedom and resistance through reading about historical figures like Garibaldi and forming a secret group with fellow students even if the said freedom is imaginary and meant breaking a few unfounded rules of the white man involving basic disobedience or smoking stolen cigarrettes in order to escape the harsh reality of mental and physical abuse of the worst kind including the sexual abuse at the hands of senior students as well as some of the priests in the seminary.

God, Gold and Glory: The front(s) of Colonialism

The book delves deeply into the themes of religious colonialism. Author personally considers it worse than territorial colonialism, referring to it as the 'torturing of the soul', for it creates an atmosphere of fear, uncertainty, and general suspicion. The seeds of hateful spread in Abrahamic faiths, particularly Christianity for a large portion of world's history and geography for more than 300 years before the second World War was evident in the Latin saying, "Cuius regio, eius religio" (whose realm, their religion). The blood curdling episodes of inquisition, “witch” hunting, shrine destructing and the burning of indigenous knowledge that went on in Christian (and Islam) occupied countries are well recorded.

Author shares his disturbing experience at the mission by describing how he along with ten other children was kidnapped and kept there, all of them at a very young age who were not allowed to see their parents (nor was their parents allowed to see them). They were beaten when asked question and were asked to wear a disgusting severed goat's head around their neck if found speaking one word in their native language, worse even, the students were asked to told upon the next student they find speaking in language other than French if they want to get rid of the goat symbol, this way the Jesuit ensures a self-regulating and vigilant behavior from the children who without even knowing were slowly transforming into the native missionary force.

Religious Colonialism is an ongoing phenomenon and a problem for many postcolonial countries and does operate as a tool of neo-colonialism. Author discusses that in his tribe there are no two spaces for divine and secular. The western concept of secularism not only separates and compartmentalises certain spaces in religious and non-religious it deliberately creates a crisis by weaponizing rationality in secular spaces and exploiting opportunity in the religious one's. The borrowed concept of western secularism has thus reaped more followers for Christ than the great flood.

The author evaluates how religious colonialism enforces itself with the help of local people in remembering, "Our teachers were Black, from the tribe, yet they were our worst enemies". He also blames the political instability in the African sub-continent of today to the erosion of native culture by the colonial ethos and disastrous western model of education which is undoubtedly designed to serve someone and some purpose.

Initiation and the Awakening

"... can a hyena and a goat learn to walk together?"

The book talks at length about the 'two lives' of Malidoma, his long 15 years exile at seminary which had given birth to a sense of an imagined freedom in his still forming mind to his initiation into his own culture which, as is said, was meant to make a 'man out of a boy' and 'to mend his broken spirit' (bringing back the part that was left behind in the land of white man). His coming back to the village produced a crisis due to his time spent among white men, he was considered to be swallowed by the foreign way of life due to his absence from the village and his initiation at the hands of colonisers.

The author passionately discusses in several remarkable chapters the process of his initiation never shying away from talking about the magic and supernatural involved in the process, even trying to make it sound believable to a non-Dagara. He goes on narrating about his experience of rebirth from the elements of earth, water, and light and his journey to the enchanted realm underground where he had a recollection of his past life memories among other experiences that which had brought back the harmony to his soul and spirit unifying him with the ways of his ancestors where there is no supernatural only broadened perspective.

The idea of individuals who were educated in Western ways but ultimately returned to their own cultural roots and fought against colonialism (religious or otherwise) is not unheard of. There are parallels between their experiences in their calling to service, renowned figures like Swami Vivekananda, Mahatma Gandhi, Sri Aurobindo, and Gurudev Rabindra Nath Thakur are few of the many names and examples who were born and brought up under an oppressive British regime in the colonial India, and shared the same century as Malidoma. Despite being raised and educated in Western cultures, these individuals rejected foreign influences, embraced their own cultural identities, and became advocates for their people and their voices into the world. Malidoma was repeatedly reminded by his elders of his destiny and his purpose in life which he was named after, "you may serve as the eye of the compound, the ear of your many brothers, and the mouth of your tribe'', his grand-father prophesied. The book explores his long painstaking journey to and fro the land of white man in order to take the word and wisdom of his people to the West and take back knowledge that he had gained from there to back home in order to the world to know if a hyena and goat can walk and exist side by side.

Conclusion

Some's literal presentation of the Dagara tribals, one of the least contacted tribe in the written history is truly fascinating on many accounts but one particular reason that stands out is not it's difference but the subtle similarities that it has with several other, largely unrelated, (not just tribal) cultures around the world, mainly the ones from Asia. The Ancient Indian tradition can easily be spotted for its many similarities with the Dagara's. One can draw a number of examples from the book like the presence of a Matrilineal society, where the mother is the head of the household, to a village council of elders. Free basic education to all children aimed at teaching important life skills including the knowledge of medicine and astronomy and not just mindless rote learning, a brilliant instrument of colonialism invented and introduced by Europeans. The exalted position of elders and strong community ties shared by Dagara's was another one such mark of a proud tradition in many non-west cultures before they became endangered in their own home thanks to the systematically introduced destructive technologies and the ever increasing philosophical-isms, another western export.

The Dagara wisdom regarding the accumulation of wealth and material well-being bears a recognizable strain of the ancient Vedic and Buddhist teachings of the Indian subcontinent, author tells us that, ''wealth among the Dagara is determined not by how many things you have, but by how many people you have around you". Even if the two cultures had never interacted, the similarities makes them a sister civilization. Both violated at the hands of invaders and faced persecution at the hands of colonising Abrahamic faiths.

Even the post-colonial experience of these third world countries also bears an uncanny resemblance, in the words of the author, ''... most of the young men and women were confused: they were neither Westernized nor traditionalized'', which in itself presents a big challenge in the face of neo-colonialism. Some's work is an important read which fairly establishes the need for the revival of the indigenous tradition, for achieving true freedom and going through the much-needed initiation for the nation and its people in order to rid ourselves of the hindrances in the flow of water and the spirit.

- 64 min read

- 7

- 0