- Visitor:97

- Published on:

Greater India: The cultural expansion of Indic civilization

The unique feature of India’s contacts and relationship with other countries and peoples of the world is that the cultural expansion was never confused with colonial domination and commercial dynamism far less economic exploitation. That culture can advance without political motives, that trade can proceed without imperialist designs, settlements can take place without colonial excesses and that literature, religion and language can be transported without xenophobia, jingoism and race complexes are amply evidenced from the history of India’s contact with her neighbors.

Indian culture was never an isolated growth. One of the most original and significant contributions of India to human civilization is the way of behaving with the neighbors. India has always friendly relations with her neighbors. Of course, there was some stray instances of Indian kings undertaking expeditions in neighboring countries. But these exceptions prove the rule that normally the Indians were not interested in the territories of their neighbors.

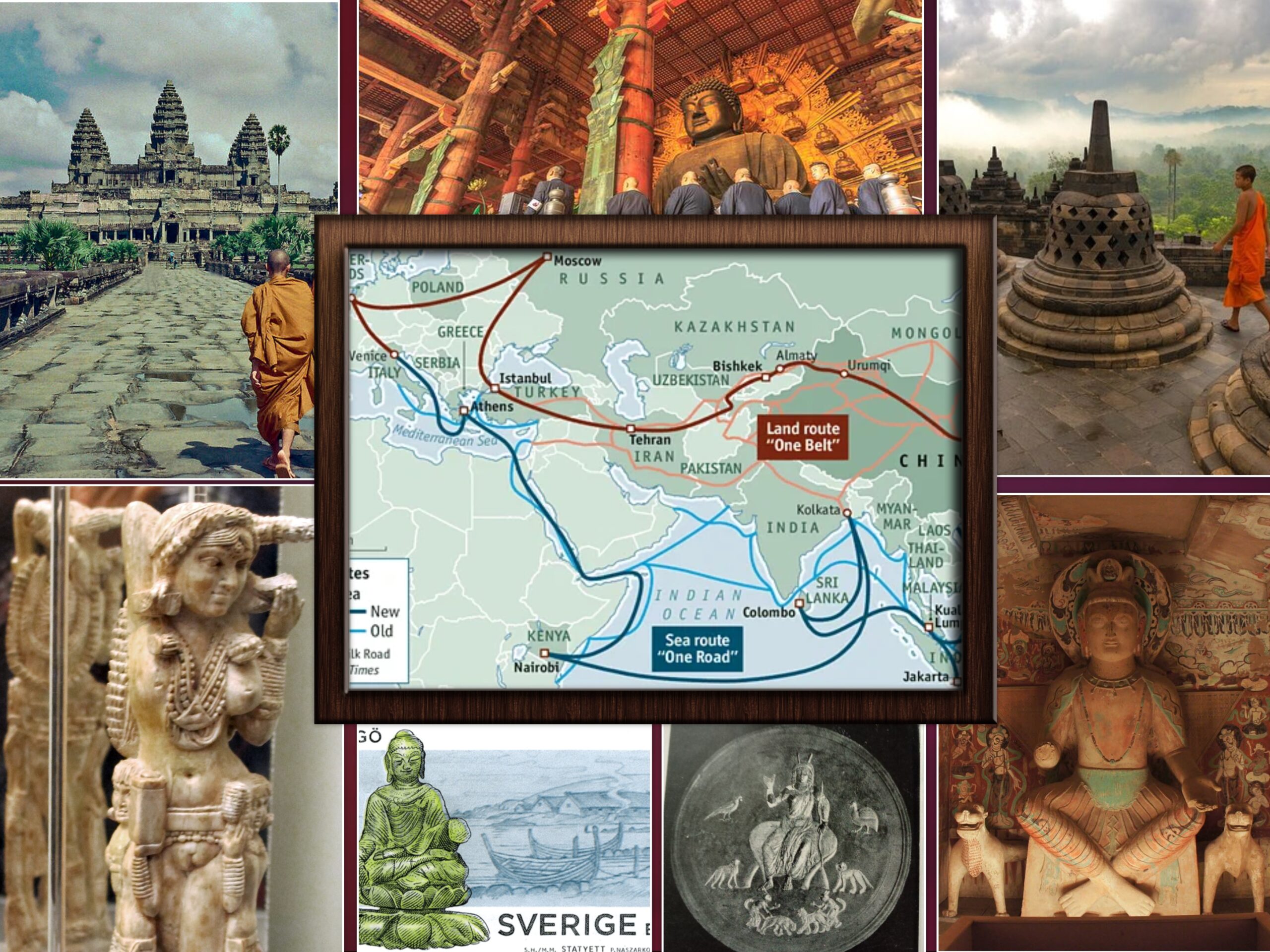

Although we have little instances in India of covering the territories of the neighbors, we have abundant evidence of their close commercial and cultural contacts with them. Interminable trains of Indian traders, sailors, missionaries, artists and settlers crossed the arid deserts of north and the high seas of the south and peacefully spread their culture in the Tarim Basin along the silk route up to China, Korea and Japan and in the Indo-China and Indonesia and possibly further into the Pacific in the east and western Asia, Madagascar, Egypt and the Sudan, the Greco-Roman world, Gaul and Scandanavia in the west. The extent of the expansion of Indian culture abroad has been rightly described by S. Levi: “From Persia to the Chinese Sea, from the icy regions of Siberia to the Islands of Java and Borneo, from Oceania to Socotra, India has propagated her beliefs, her tales and her civilization. She has left indelible imprints on one fourth of human race in the course of a long succession of centuries. She has the right to reclaim in universal history the rank that ignorance has refused her for a long time and to hold her place among the great nations, summarizing and symbolizing the spirit of humanity.”

The voluminous output of evidence – Buddha image in Scandinavia, summary of the Upanishads in Rome, ivory statuette of Lakshmi at Pompeii, silver dish depicting Mother India at Lampascus, sheets of manuscripts of Aryaprajnaparamita in Romania, south Indian finds in Sudan, bronze image of an Indian danseuse in south Arabia, burial of South Indian people Kalaly-gry-I in Khorezm, Sanskrit manuscript in three parts in a decorated vase at the site of old Merv in Turkmenia, remains of a silk bale bearing price in Brahmi script and the fragments of the Bower Manuscript and the dramas of Asvaghosha on the silk route in the Tarim basin, caves of thousand Buddhas on the frontier of China, Angkor Thom and Angkor Vat in Indo-China, Borobudur in Indonesia, the temples and sculptures of Korea and Japan are sure proofs of global expansion of Indian culture.

For more than one thousand years’ Indian religions were professed, Indian languages were spoken, Indian scripts were written, Indian poems were sung and Indian social values were acknowledged by a large number of peoples in many parts of the world. In this process of intense and intimate cultural contacts India received from others as much as she gave to them. This cross-fertilization of ideas, this commingling of values, the interpenetration of strands produced an organic, synthetic and integrated cultural development which shaped the patterns of life of considerable sections of the human race.

The unique feature of India’s contacts and relationship with other countries and peoples of the world is that the cultural expansion was never confused with colonial domination and commercial dynamism far less economic exploitation. That culture can advance without political motives, that trade can proceed without imperialist designs, settlements can take place without colonial excesses and that literature, religion and language can be transported without xenophobia, jingoism and race complexes are amply evidenced from the history of India’s contact with her neighbors.

The process of India’s cultural contacts with the world was conditioned by an upsurge and overflow of the spirit of movement and expansion among the Indian people. It is significant that merchants, mariners, travelers, adventurers, peddlers, jugglers, astrologers, medicine men, missionaries and monks immersed themselves in this movement, whereas kings, courtiers, diplomats, generals, administrators and government officials were by and large indifferent to it. In the earlier stages it was carried on by the backward tribes of Australoids and Dravidoid origins. Then people of higher classes, mostly traders and merchants began to take interest in it. And afterwards about the beginning of Christian era men of all castes and callings plunged headlong into it and accelerated its sweep and momentum.

These people represented India without any royal mandates, imperial character, political directive or military assistance. They moved by their own inner impulse of advance and adventure rather than the outer pressure of political impetus or military stimulus. They set out of their own accord and not by any order of the government.

It is, therefore, but natural that their outlook was peaceful and their approach co-operative. They knew the art of persuasion and followed the methods of winning over the foreigners to their side. Thus although a considerable part of central and South-eastern Asia became flourishing centers of Indian culture, they were seldom subjects to the regime of any Indian king or conquerors and hardly witnessed the horrors and havocs of any Indian military campaign.

They were perfectly free, politically and economically and their people representing an integration of Indian and indigenous elements had no links with any Indian state and looked upon India as a holy land rather than a motherland – a land of pilgrimage and not an area of jurisdiction. Thus to say in a nutshell, the hall-mark of the Indian approach to the world is the realization that cultural expansion is free from economic exploitation, that the colonial settlement is different from political bondage and contacts between peoples of different parts of world are determined by the factors of peaceful co-operation rather than the consideration of military aggrandizement.

The natural frontiers of India did not prove insurmountable for the flow of her cultural contact with the rest of the world. It is a truism that from time immemorial India has been carrying on peaceful intercourse, both political and commercial with the all nations of the planet in the east as well as in the west. There is good reason to believe that the connection with the west has subsisted from the very earliest period of the history of humanity. There is strong evidence of an ancient and flourishing trade between India and the nations in the east, as testified by the early importation of Chinese silk into India. it is also a well-nigh established fact that the people of south India had a very large part to play in this maritime trade. In remote antiquity India had trade relations with Mesopotamia, Syria and Egypt.

We have also evidence that the Aryans were most probably immigrants from South-East Europe. It is now obvious that India “gave” and “took” the gains of cultural admixture: and the Indian influences flowed into foreign lands and at the same time the foreign influences freely migrated into India. This results in the developing of the Indian culture, as it led to the foundation of a “Greater India” beyond the seas.

It was India that functioned there and exhibited her vitality and genius in a variety of ways. We thus see her carrying not only her thoughts but her other ideals, her art, trade, language, literature and methods of government. M. Rene Grousset enumerates the countries which went under Indian cultures: “In the high plateau of eastern Iran, in the oases of Serindia, in the arid wastes in Tibet, Mongolia and Manchuria, in the ancient civilized lands of China and Japan, in the lands of the primitive Mons and Khmers and other tribes in Indo-China, in the countries of the Malaya-Polynesians, in Indonesia and Malaya, India left the indelible impress of her high culture, not only upon religion, but also upon art and literature, in a word all the higher things of spirit.”

This Indian spirit is to be seen pulsating from the Brahmaputra to the Tonkin Gulf. As Geraini commenting on Ptolemy’s Geography rightly observes: “From the Brahmaputra and Manipur to the Tonkin Gulf we can trace a continuous string of petty states ruled by those scions of the Kshatriya race, using the Sanskrit or the Pali language in official documents and inscriptions, building temples and other monuments of the Hindu style and employing Brahmin priests at the propitiatory ceremonies connected with the court and the state.” B.G. Gokhale rightly observes: “Looking at the cultures of the people of Asia in general and south east Asia in particular, the awareness grows upon us that what we see in Burma or Siam or Indonesia is but an extension of Indian culture – they could be legitimately called a Greater India.”

Bibliography:

Some Preliminary observations, Greater India, Arun Bhattacharya, Published 1981, pp. 1-4.

Center for Indic Studies is now on Telegram. For regular updates on Indic Varta, Indic Talks and Indic Courses at CIS, please subscribe to our telegram channel !

- 48 min read

- 1

- 0