- Visitor:25

- Published on:

The Indian Village Potter

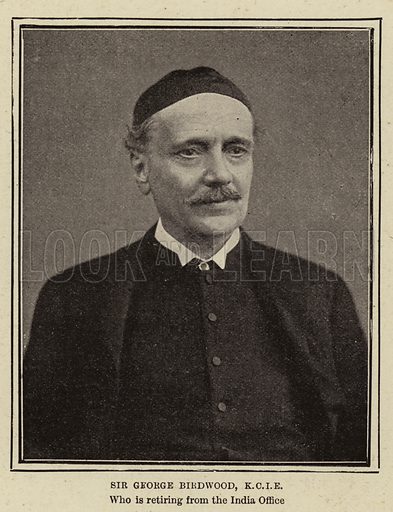

“To the Indian land and village system we owe altogether the hereditary cunning of the Hindu handicraftsman. It has created for him simple plenty, and a scheme of democratic life, in which all are co-ordinate parts of one undivided and indivisible whole, the provision and respect due to every man in it being enforced under the highest religious sanctions, and every calling perpetuated from father to son by those cardinal obligations on which the whole hierarchy of Hinduism hinges”- by Sir George Birdwood

Sir George Birdwood on the Indian Village Potter.

“The Indian potter’s wheel is of the simplest and rudest kind. It is a horizontal fly-wheel, two or three feet in diameter, loaded heavily with clay round the rim, and put in motion by the hand; and once set spinning, it revolves for five or seven minutes with a perfectly true and steady motion.

The clay to be moulded is heaped on the center of the wheel, and the potter squats down on the ground before it. A few vigorous turns and away spins the wheel, round and round, and still and silent as a “sleeping” top, while at once the shapeless heap of clay begins to grow under the potter’s hands into all sorts of faultless forms of archaic fictile art, which are carried off to be dried and baked as fast as they are thrown from the wheel. Any polishing is done by rubbing the baked jars and pots with a pebble. There is an immense demand for these water jars, cooking-pots, and earthen frying-pans and dishes. The Hindus have a religious prejudice against using an earthen vessel twice, and generally it is broken after the first pollution, and hence the demand for common earthenware in all Hindu families. There is an immense demand also for painted clay idols, which also are thrown away every day after being worshipped; and thus the potter, in virtue of his calling, is an hereditary officer in every Indian village. In the Dakhan the potter’s field is just outside the village. Near the field is a heap of clay, and before it rises two or three stacks of pots and pans, while the verandah of his hut is filled with the smaller wares and painted images of the gods and epic heroes of the Ramayana and Mahabharata. He has to supply the entire village community with pitchers and cooking-pans and jars for storing grain and spices and salt, and to furnish travelers with any of these vessels they may require. Also, when the new corn begins to sprout, he has to take a water-jar to each field for the use of those engaged in watching the crop. But he is allowed to make bricks and tiles also, and for these he is paid, exclusively of his fees, which amount to between £4 and £5 a year. Altogether, he earns between £10 and £12 a year, and is passing rich with it. He enjoys, beside, the dignity of certain ceremonial and honorific offices. He bangs the big drum, and chants the hymns in honor of I ami, an incarnation of the great goddess Bhavani, at marriages; and at the dowra, or village harvest home festivals, he prepares the barbal, or mutton stew. He is, in truth, one of the most useful and respected members of the community, and in the happy religious organization village life there is no man happier than the hereditary potter, or Kumbar.

“Are not these the conditions under which popular art and song have everywhere sprung, and which are everywhere found essential to the preservation of their pristine purity? To the Indian land and village system we owe altogether the hereditary cunning of the Hindu handicraftsman. It has created for him simple plenty, and a scheme of democratic life, in which all are co-ordinate parts of one undivided and indivisible whole, the provision and respect due to every man in it being enforced under the highest religious sanctions, and every calling perpetuated from father to son by those cardinal obligations on which the whole hierarchy of Hinduism hinges. India has undergone more religious and political revolutions than any other country in the world; but the village communities remain in full municipal vigor all over the peninsula. Scythian, Greek, Saracen, Afghan, Mongol and Maratha have come down from the mountains, and Portuguese, Dutch, English, French and Dane up out of its seas, and set up their successive dominations in the land; but the religious trade union villages have remained as little affected by their coming and going as a rock by the rising and falling of the tide; and there, at his daily work, has sat the hereditary village potter amid all these shocks and changes, steadfast and inchangeable for 3,000 years, Macedonian, Mongol, Maratha, Portuguese, English, French and Dane of no more account to him than the broken potsherds lying round his wheel.”

Source: Appendix I, The Indian Craftsman, by Ananda Coomaraswamy, pp. 97-100

Center for Indic Studies is now on Telegram. For regular updates on Indic Varta, Indic Talks and Indic Courses at CIS, please subscribe to our telegram channel !

- 12 min read

- 0

- 0