- Visitor:82

- Published on:

Psychology of Jesus

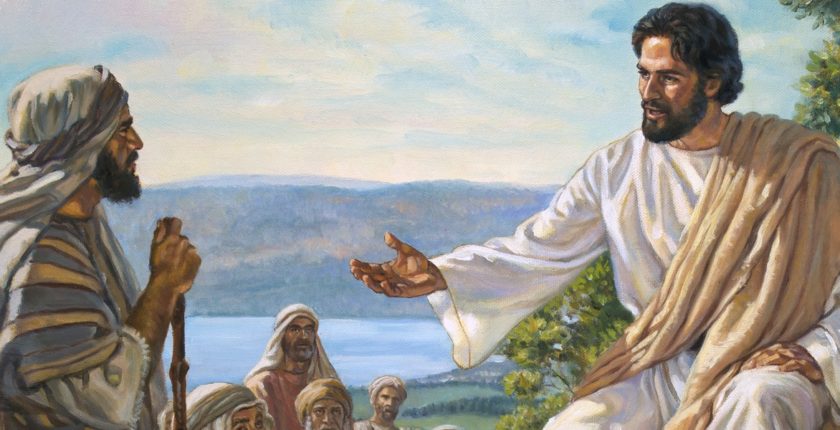

Everyone knows that the sources on Jesus’s life are insufficient for writing his biography. But they are sufficient to reach the conclusion that he was a pathological personality. At any rate, these are the conclusions which liberal theology has reached by thinking and taking into account the findings of modern psychiatry.

Nietzsche on Jesus

The first to take on Jesus as a psychologist, though not as a medically trained psychopathologist, was the German scholar and philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, one of the greatest critics of Christianity (who ended up suffering an irreversible mental breakdown himself).1 Like many Christians, he thought that the historical Christ was a very different man from the Christ of theology. Thus, Christ had renounced the law and chosen a life of childlike innocence, whereas the Churches had built an elaborate system of morality on top of his teachings.

However, unlike some softhearted poetic Christians who felt unhappy with dogmatic Christianity and attracted to the experiential Christianity of Christ himself, Nietzsche rejected this original religion of Christ. For him, Christ was a decadent. This somewhat technical term in Nietzsche’s philosophy means: someone who has given up worldly ambitions, who is tired of the world with its passion and struggle, who wants to retire to some kind of paradisiacal sphere. Such a prophet may be good for people who are tired of this world, weak and unhappy people, losers.

In Nietzsche’s assessment, Jesus was anti-world, anti-mighty, anti-order, anti-hierarchy, anti-labour, anti-struggle, anti-difference. Total non-struggle, surrender, softness, love. That is the Jesus who is still somewhat popular among those few young dreamers attracted to Christianity. Tolstoy thought this was the real Christ, sharply different from the Church’s Christ created by Saint Paul. For instance, obedience to the worldly authorities is a duty for Church Christians, not for the original Christ. Nietzsche, while agreeing with Tolstoy on the contrast between Jesus and the Church teachings, does not follow him in choosing for the original Jesus. He merely sees two forms of decadence at work, both to be rejected. But he will agree that Jesus’s attitude was his own problem, whereas Saint Paul’s attitude (and theology) has sickened an entire civilization.

While Jesus preached a spontaneous and unconcerned life, his posthumous disciple Paul, the first Christian, would build a full-fledged theology out of a few elements of Jesus career and teaching, an ideological system that has very little to do with the actual Jesus. For Jesus, the concepts of Sin and of Law had lost all meaning. He believed in sinlessness, no need to tread any specific path of morality to avoid sin. But in Christianity, sin becomes the raison d être of religion: Christ has come, suffered and risen in order to save humanity from sin.

And yet, somehow this Salvation is not complete, because on top of it, man must also go under the yoke of a system of morality, adapted with strong simplification (de-ritualization) from the Mosaic Law, in order to earn his place in Heaven. It is this emphasis on dry morality that has made Pauline Christianity so unpopular among the pleasure-seeking section of humanity. A lot of modern Western literature is about people outgrowing their tense submission to Christian morality. Some Protestant sects have decided that morality is not instrumental in our Salvation (though for the sake of public order they support morality and explain that one’s degree of morality is a sign, but not a factor, of one’s predestination for either Heaven or Hell), but they too stick to the notion of sin as fundamental to the human condition until Jesus saves us.

The question of salvation through one’s own works or through mere faith inJesus autonomous act of Salvation is a much-debated one among Christian thinkers including Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Luther, Calvin etc. The controversy exists, mutatis mutandis, in some other traditions too, e.g. Shaiva Siddhanta. Borrowing a Shaiva metaphor, we might say that Christianity too has advocates of the way of the kitten, which is grabbed by its mother and saved without effort, and of the way of the baby monkey, which clings on to its mother and is saved through its own effort. But in Christianity, unlike Shaivism, one is saved not from ignorance about one’s own ever-divine Self (i.e. restored to one’s own intrinsic divinity), but from one’s own ever-sinful self. No one is a Christian if he does not accept that we human beings are all intrinsically sinful, and that Jesus has come to save us from sin. But, all according to Nietzsche, Jesus never cared about sin. Contrary to Jesus, Christianity feeds us an obsession of being profoundly evil and God-alienated.

At this point we must comment that Nietzsche has taken the traditional image of Jesus too much for granted, an image built on those Bible stories that are the most likely to be inserted borrowings from other sects, such as the Sermon on the Mount. In the more reliable Gospel passages, we find that the historical Jesus was not the exalted, ever-innocent pacifist and passivist he is often made out to be.

One thing that Nietzsche has against the Christianity of the Church still dominant in his time, is that it is not religious enough. Religion for Jesus was a revolutionary thing, an extreme thing. And while Jesus’s religiosity was bizarre and unintegrated in the world (it was an anticipation of the Kingdom of Heaven expected soon), it has a certain kind of uncomplicatedness and cheerfulness about it which is proper in a healthy religion. But Pauline moralistic Christianity is drab, unhealthy, worrisome, negatively limiting without offering anything positive and great in return. Nietzsche’s own religiosity is a longing for the superhuman which transcends human smallness. It is the antithesis of Pauline Christianity, which to him seems to have nothing great and mentally uplifting to it.

While Christ’s religion is centered on love and surrender, Paul’s Christianity becomes, in Nietzsche’s analysis, the religion of hatred and revenge. Paul was obsessed with the Law, the central topic for the Pharisees. He was painfully aware of man’s (esp. his own) incapability to live up to the letter of the Law. Fortunately, Christ has delivered us from the Law, and replaced it with the law of love: a revolution. So far, Paul is in tune with the spirit of Christ, as Nietzsche understood it. But in Paul’s vision, this revolution comes hand in hand with another revolution, in one movement: the abrogation of the Law is the ideological starting-point of Christianity’s mission among the Gentiles. Paul’s life, and with it that of many others, will no longer be burdened with the Law, but will now burden itself with a new task, unprecedented in history. Paul breaks with Judaism and its oppressive Law observance, and starts to win the rest of humanity for Christ. His own frustrated desire to live up to the demands of the Law, now gets transformed into a tremendous ambition to spread his new-found religion of Salvation through Christ.

Nietzsche draws the parallel with Luther, who had aspired so earnestly to live an ascetic life and fulfill the commandments imposed by Church teaching, but had ended up hating the Church and the pope and the monastic rules so bitterly that he became their declared enemy, crusading to spread an alternative. Paul is so tired of the Law, that he turns into a follower of its declared enemy, Jesus, once a psycho-physiological crisis had broken through his resistance. As Dr. Somers has shown, this crisis, befalling Paul on the road to Damascus, was a sunstroke, of which the effects and sensations were afterwards interpreted as a divine revelation. Once this liberating decision to break with the Law has its exalting effect on him, he feels that this solution for him, is also the solution for mankind. He will now become the apostle of the destruction of the Law, which has been replaced by faith in Christ.

Saint Paul was not a prophet, but he was a political genius. He saw the potential of his new doctrine and of the situation in the Roman empire, especially the provincial towns. Away from the worldly turmoil of Rome and from the extremist zealotry of Palestine (two places where the Christians would encounter plenty of martyrdom), Paul found the optimum terrain for the onward march of his new religion. In these towns (in Greece and Asia Minor), he would set up communities that would imitate the social ways of the Jewish communities spread across the Empire, with their honourable inconspicuous lives as craftsmen and traders, with their mutual support and communal solidarity, and with their quiet sense of superiority as the Chosen People. Instead of the unbearable burden of the Mosaic law, he would give them some petty bourgeois morality, but all the same he would promote among them this communal superiority feeling of being the Saved ones in Christ.

The contrast between Jesus and Pauline Christianity, is treated by Nietzsche as a contrast between two doctrines. Nietzsche does not really analyse Jesus’s personality, self-perception or public image. He mistrusts the historicity of the Gospels. At the time, the critical method of investigating the historicity of pieces and layers of text was not as refined, and especially the psychological analysis which 20thcentury psychologists tried out on Jesus, was not yet at his disposal. So, his psychological evaluation of Jesus, and of Saint Paul, the creator of Christianity, concerns more the ideology they represent than their historical personalities. Nietzsche puts their personalities between brackets, and concentrates on the ideologies that their (doubtlessly distorted) Biblical biographies represent.

One might say that Nietzsche’s view of Jesus was very one-sided. The peaceful apostle of love is a popular image of Jesus based on only a few gospel texts: the Sermon on the Mount; when you get slapped, offer the other cheek also; he who lives by the sword shall perish by the sword; the lilies of the field don’t toil, yet Solomon in his splendour was not as good-looking as any of them; do not judge lest you yourself by judged. These passages are of disputed historicity, while many reliably historical passages show us a very different Christ: short-tempered, defiant, and a Doomsday prophet. The gentle Jesus, who was in Nietzsche’s view the original Jesus whose teaching and example were later deformed by Pauline Christianity, was himself just as much a creation of his second-generation disciples.

While Nietzsche’s evaluation of Christ is somewhat marred by the immaturity of the historical research on Christ, his understanding of the Old Testament already had the benefit of a Biblical scholarship that has, in great outline, been confirmed by the more recent scholarship. The chronology of the Old Testament had more or less been established, and the political context of the successive stages of editing were already understood.

According to Nietzsche, Yahweh’s support for his people came to be seen as conditional and dependent upon the Hebrews’ own behaviour, when they had become losers on the international scene. God was no longer seen to be giving them victory, so they tried to regain control over their destiny by assuming God’s support to be dependent upon their own moral behaviour (observance of the Law). Nietzsche considered the Bible’s emphasis on morality as a revenge operation of a defeated people: winners are not burdened with morality, which is the weapon of the losers.

Nietzsche has paid little attention to the next stage in Israel’s religion. During the period of the exile, prophets like Jeremiah, Ezekiel and deutero-Isaiah had again disconnected God s sovereign decision from man s degree of obedience to God’s will. Man’s morality and law-abidingness no longer make a difference: God’s judgment has already been determined, his final intervention will come anyway, and our Salvation will be brought about not by our own goodness but by the Messiah. The apocalyptic stage in the doctrinal development in Hebrew religion, which will culminate in the Jewish rebellions of the first and early second centuries AD, was already appearing on the horizon at the time of the exile, when the classical doctrine of the Covenant, the mutual contract between Yahweh and His chosen people, was still being formulated and imposed upon Israel’s history through the final Bible editing.

While Nietzsche’s analysis concerns ideologies or collective mind-sets rather than persons, and while some of his insights have simply become outdated by the newest Bible research, he has the merit of being one of the first to apply human psychology to the supposedly divine revelation embodied in the Bible. He was instrumental in breaking the spell that had been shielding the Bible from critical inquiry. Moreover, unlike the radical atheists and skeptics who simply disregarded the Bible or dismissed it as fable, Nietzsche took the more balanced position of honouring it as a highly interesting and psychologically revealing human document.

Psycho-analyzing Jesus

Shortly after Nietzsche made his psychological analysis of what he understood as Christian doctrine, rightly or wrongly attributed to the historical Jesus by the Gospel editors, professional psychologists tried to get at the historical personality of Jesus. In the beginning and more even at the end of this twentieth century AD, psychology has thrown a mighty new light upon the development of the Abrahamic or prophetic-monotheist lineage of religions.

Since the dawn of modem Western psychology, the Bible has interested psychologists. Freud, the Austrian-Jewish father of psychoanalysis, gave a lot of attention to the character of Moses.2 For example, in Freudian theory, Moses lack of a normal father relation (according to the Bible, he was a foundling brought up in the Egyptian court) made him an excellent object of study: this circumstance could have accounted for his sternly authoritarian and patriarchal conception of God. Even more unorthodoxly, Freud claimed that Moses had not been a Jew but a high-placed Egyptian: fearing trouble after committing a murder, he had joined the impending Exodus of the beleaguered Jewish immigrant community.

Freud was very hesitant to publish his work on Moses, because he expected it to shock the Jewish community, and that at a time when Nazi Germany was taking one anti-Jewish measure after another. Freud’s work is in many ways outdated, but remains of great importance in this context because he did, even while expressing his great scruples and hesitation, what many believing Jews and Christians could not intellectually tolerate: he looked at the founder of his religion through the inexorable eyes of scientific analysis. Some other older psychological studies of Bible characters include C.G. Jung’s study of job and K. Jaspers study of Ezekiel.

Probably the first attempt to analyze Jesus was made in the late 19thcentury by the French neurologist Jules Soury, also known as the secretary of Ernest Renan. Inspired by remarks by David Friedrich Strauss, who had called Jesus a rabid fanatic, Soury wanted to go beyond scornful rhetoric and apply the budding science of neurology to the case of Jesus. However, it was the heyday of materialism in the human sciences, and with the conceptual instruments at his disposal, he could hardly do justice to psychic phenomena. In his diagnosis, he settled for a highly disputable verdict which we would consider more physiological than psychological: progressive paralysis.

The first truly psychopathological diagnosis of Jesus was made separately by three psychiatrists, W. Hirsch, Ch. Binet-Sanglé, and G.L. de Loosten. After thorough examination of the Gospel narratives, they independently reached the same conclusion: Jesus was mentally ill and suffered from paranoia.3 In E. Kraepelin’s classification of mental diseases, paranoia is defined as the sneaking development of a persistent and unassailable delusion system, in which clarity of thought, volition and action are nonetheless preserved.

In his reply, the Christian theologian and famous medical doctor, Albert Schweitzer, admitted: if it were really to turn out that to a doctor, Jesus world-view must in some way count as morbid, then this must not – regardless of any implications or the shock to many – remain unspoken, because one must put respect for the truth above all else. But he rejected the psychiatrists’ conclusions.4

Schweitzer alleged that from a historical point of view, most texts were dubious or certainly not historical, e.g. the quotations from the Gospel of St John, the most theologically polished and least historical of the four Gospels; and that from a medical point of view, the alleged symptoms were misunderstood. Three objections seemed essential:

There is no certainty about the historical truth of the texts;

What seems to us to be a symptom, was possibly a normal trait, a cultural feature in that civilization;

There are not enough fully reliable elements in order to base a safe judgment on them; even the pathological symptoms claimed, viz. pathological Ego-delusion and hallucinations, are insufficient to conclude a definite diagnosis.

These objections can be met, as we shall see in subsequent chapters. The last of the three can be met right away: if a psychiatrist notices both hallucinatory crises and an Ego-delusion in a patient, he will most certainly conclude that these are symptoms of a mental affliction, and this all the more certainly if they can be identified as a known syndrome, and are accompanied by a number of coherent typical behavioral features.

Dr. Schweitzer was not a psychiatrist, but his Doctor s title was already enough to put all doubts to rest. After his reply the Churches felt reassured, and few outsiders made new attempts to psycho-analyze Jesus.

An exception is Wilhelm Lange-Eichbaum, with the chapter. The problem of Jesus in his book Genie, Irrsinn und Ruhm (German: Genius, Madness and Fame ), of which we have excerpts from the third edition at our disposal: it was still prepared by the author himself in 1942, while the fourth edition of 1956 has been seriously tampered with by outsiders, esp. in this chapter.5

Dr. Lange-Eichbaum writes: The personality during the psychosis (we only know Jesus during this life stage) is characterized by quick-tempered soreness and a remarkable egocentrism. What is not with him, is cursed. He loves everything that is below him and does not diminish his Ego: the simple followers, the children, the weak, the poor in spirit, the sick, the publicans and sinners, the murderers and the prostitutes. By contrast, he utters threats against everyone who is established, powerful and rich, which points to a condition of resentment. In this, all is puerile-autistic, naive, dreamy. In this basic picture of his personality, there is one more trait that is clearly distinguishable: Jesus was a sexually abnormal man. Apart from his entire life-story, what speaks for this is the quotations of Mt. 19:12 (the eunuch ideal), Mk. 12:25 (no sex in heaven, asexuality as ideal) and also Mt. 5:29 (removing the body parts that cause sin: intended are certainly not hand and eye). The cause may have been a certain weakness of libido, as is common among paranoia sufferers

There is a lack of joy in reality, extreme seriousness, lack of humour, a predominantly depressed, disturbed, tense condition; coldness towards others insofar as they don’t flatter his ego, towards his mother and siblings, lack of balance: now weak and fearful, now with violent outbursts of anger and affective lack of proportion According to both modern and ancient standards, he was intellectually undeveloped, as Binet has extensively proven; but he had a good memory and was, as is apparent from the parables, a visual type. Binet also emphasizes the lack of creativity. A certain giftedness in imagination, eloquence and imaginative-symbolic thought and expression cannot be denied. He was certainly not a genius in the strict modem sense. The later psychosis is however in no way in contradiction with his original giftedness which was above average: in paranoia this is quite common.

The entry in Jerusalem is doubtlessly the result of increased excitement: psychically, Jesus is on fire. For laymen as well as for theologians, there is something painful and absurd about this entry. Isn’t the psychotic streak all too obvious here? Hirsch calls the parade on the donkey absurd and ridiculous and Schweitzer too finds it painful. It is only enacted to fulfill the Messiah prophecy, secretively and for the eye of his followers. It may be sad or tragic-comical that the buffoon-king is making his entry this way. Nowhere is the purposeless nature of psychotic activity more in evidence than in the entry in Jerusalem: his acts lack any logic. What does Jesus want? He is tossed this way and then that way. Worldly power? Yes and no. Messiah claim? Yes and no. Defiance and death wish? Yes and no.

The exact diagnosis is not that important for us. A paranoid psychosis: that may be enough. Maybe real paranoia, maybe schizophrenia but without irreversible decay, in the form of a paraphrenia. Or a paranoia based on an earlier slightly schizophrenic shift. Anyone checking with the extant scientific literature is struck by the remarkable similarity of the symptoms.

Dr. Lange-Eichbaum’s diagnosis belongs to an earlier stage in the development of psychopathology, when all kinds of explanations were read into symptoms, without using strict criteria. Freud’s psycho-analysis is so notoriously full of unfalsifiable statements (i.e. impossible to prove wrong, escaping every cold test) that Karl Popper classifies it among the pseudo-sciences along with astrology. Dr. Lange-Eichbaum stays closer to factual reality in his description of symptoms, but is hazy in the formulation of a final diagnosis. Moreover, his knowledge of the Biblical backgrounds and the Roman-Hellenistic cultural milieu are limited, so that many possibly pertinent facts escape his attention. We would have to wait for Dr. Somers’ multidisciplinary competence to formulate a truly comprehensive diagnosis.

There is an element of modem man’s triumphalism, so typical of the Enlightenment, in Lange-Eichbaum’s conclusions: Can an intelligent and critically disposed person, who has abandoned childish beliefs and childish prejudice, seriously doubt that this is a case of psychosis? For an educated mind this psychosis is so clearly discernible that he would expect even the layman to notice it. Jesus’s destiny cannot possibly be understood without the aid of psychopathology. The dark misgiving which historical theology has had for the past 100 years, was on the right track. Anyone who surveys the extant literature, can see it with shocking clarity. The notion that Jesus was a mentally ill person, cannot be removed anymore from the scientific investigation. This notion is triumphant. First, science has brought Jesus down from his divine throne and declared him human; now it will also recognize him as a sick man.

A confirmation that the dispassionate study of Jesus as a human person leads irrevocably to a psychopathological diagnosis, is given by a Protestant preacher, Hermann Werner. Objecting to liberal theology with its historicization and humanization of the divine person Jesus (in the theological line of research known as the Leben Jesu-Forschung, investigation of Jesus’slife), he shows what becomes of Jesus when he is measured with human standards: The image of Jesus as [the liberal theologians] want to describe it in ever greater detail, got equipped with traits which made it ever less commendable. This Jesus is, no matter how much one would want to ward off this conclusion, mentally not healthy but sick. Although man’s – and certainly Jesus – deepest life, is a mystery which we cannot unveil down to its deepest roots, yet certain limits can be agreed upon within which one’s self-consciousness must remain if it is to be sane and human. There are, after all, unassailable standards which are valid for all times, for the ancient oriental as well as for the modem western. Except in completely uncivilized times and nations, no one has ever been declared entirely sane and normal who held himself to be a supernatural being, God or a deity, or who made claims to divine qualities and privileges. A later legend may ascribe such things to this or that revered person, but when someone claims it for himself, his audience has always consisted exclusively of inferior minds incapable of proper judgment. 6

Perhaps Rev. Hermann underestimates the belief of the ancient civilized Pagans in the possibility of divine incarnation, of having a divine person in their midst, in which the meaning of the word divine can be stretched a bit; but then he is right in assuming that this divine status is normally only ascribed to the revered person after his death. That the modernskepsis towards claims of being a divine person were shared by Jesus’s contemporaries, can be seen from the Gospel itself. The Jews (for whom this skepsis became indignation for reasons of exclusive monotheism) wanted to kill Jesus because he not only broke the Sabbath but also called God his Father, making himself equal with God (John 5:18), and because you, being a man, make yourself God (John 10:33).7 Either Jesus was really God’s only-born son (and by accepting that, you become a believing Christian), or his claim to divine status was absurd and abnormal by the standards of both ancients and moderns. A liberal theology which humanizes Jesus and yet remains Christian, is impossible: it is either the fundamentalist belief in Jesus divinity, or no belief in Jesus Christ at all.

Rev. Hermann concludes: Everyone knows that the sources on Jesus’s life are insufficient for writing his biography. But they are sufficient to reach the conclusion that he was a pathological personality. At any rate, these are the conclusions which liberal theology has reached by thinking and taking into account the findings of modern psychiatry.

- 41 min read

- 7

- 1