- Visitor:58

- Published on:

Dholavira Village: Cultural Diversity and Ecological Constraint

Pastoral Communities and Threats to their Animals

Geographical Setting

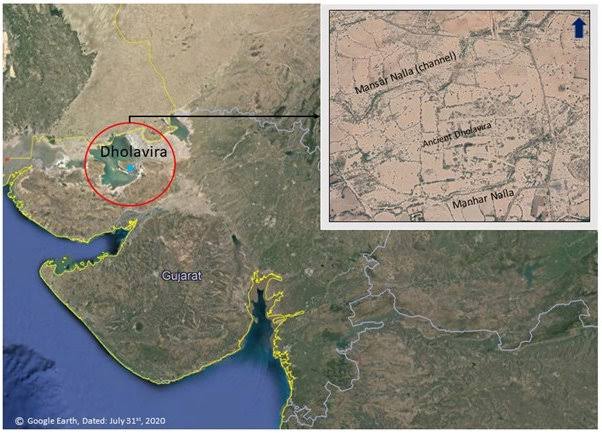

Khadir Bet

Dholavira is an archaeological site at Khadir Bet in Bhachau Taluka of Kutch district in Gujarat in western India, which has taken its name from a modern-day village 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) south of it. This village is 165 km (103 mi) from Radhanpur. Also known locally as Kotada timba, the site contains ruins of a city of the ancient Harappan Civilization. Earthquakes have repeatedly affected Dholavira, including a particularly severe one around 2600 BC. In the village of Dholavira, there are several communities like Rabari, Meghwal, Ahir and Koli. Each community adorn their own ethnic identity. These communities mostly depend upon pastoralism as Allan Savory opines that if you want to reform dead soil there is only option you have is depending upon grazing animals and pastoral communities to revitalization of land.

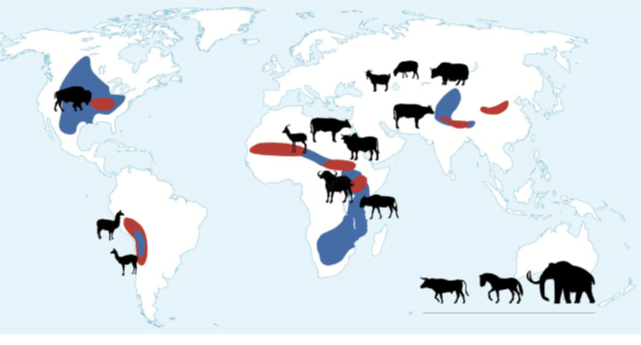

Although India has several pastorals and transhuman communities that live in different parts of the Indian subcontinent, there is a Rabari community, a pastoral community in Sindh, Gujarat, and Rajasthan regions. They used to breed goats, sheep, camels as well as cattle. They used to migrate to different areas in search of suitable grass for their animals. This migration depended upon the quality of rainfall and drought situation; depending upon the situation, they used to migrate long-distance (during drought-like conditions) and short distance (during good rainfall).

Ecological Constraint

About Rabari

Their Cultural Diversity Rabari has a remarkable migration story from the Himalayas to Punjab, Haryana, Mathura, Rajasthan and finally into Kutch via Pakistan. This community is known by different names in different states, like Rabari in Gujarat, Raika in Rajasthan, and Pal in Punjab. The Rabaris are further divided into sub-groups based on geographical location, known as parganas. Three major sub-groups residing in Kutch are the Dhebarias, Vagadias and Kachhis.

Rabari has a remarkable migration story from the Himalayas to Punjab, Haryana, Mathura, Rajasthan and finally into Kutch via Pakistan. This community is known by different names in different states, like Rabari in Gujarat, Raika in Rajasthan, and Pal in Punjab. The Rabaris are further divided into sub-groups based on geographical location, known as parganas. Three major sub-groups residing in Kutch are the Dhebarias, Vagadias and Kachhis.

Origin of Rabari Community and Related Mythology[i]

Rabari community believes that they are the progeny son of Shiva and Paravati and they have migrated from Himalayan region via Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Gujarat. In Mythology, Goddess Parvathi is the mother of these wandering gypsies. According to the first version, the story goes like this: Mata Parvathi, fondly called Mata Devi, gathered dirt, and sweat of Shiv Ji as he meditated. She moulded the collected substance into a camel. However, to her amusement, it kept running.

In the second version of the story, Lord Shiva shapes the human creature Rabari tribe to tame and mind the camels. Hence, the occupation of raising, and grazing cattle is worshipped by the Rabari community.

| Who is a Nomad? | Ecological Constraint | Pastoralism |

| Nomadism most commonly refers to a primary resource extraction strategy-be this animal husbandry, foraging, trade, or servicing-is based on recurrent physical mobility. | Environmental Constraint means natural features, resources or land characteristics that are sensitive to improvements and that may require conservation or remediation measures. | Pastoralism is a form of animal husbandry where domesticated animals known as livestock are released onto large vegetated outdoor lands (pastures) for grazing, historically by nomadic people who moved around with their herds. The species involved include cattle, camels, goats, yaks, llamas, reindeer, horse, and sheep. |

Rabari and Their Animals

Rabari and their Migration

Their access to potential grazing areas such as forests or common pastures was limited, given their low position in the local political hierarchy. Thus, certain migration patterns progressively took shape, characterized by movements from Kutch to external grazing areas and the reverse. As noted by Aparna Choksi and Caroline Dyer (1996) [ii] , migration was for the shepherds both a way to feed the animals and a way to earn some supplementary cash through labor in the farms or through the sale of clarified butter (ghee), wool or animals. Thus, migration outside Kutch was driven by several intertwined factors. The seasonal and yearly climatic variations determined what food and water was available in Kutch and in neighboring areas; the political setting determined what kind of access to pastures was possible for the shepherds; and at the economic level several options were available in and outside Kutch. Long-distance movements of the Rabari shepherds with their herds resulted from active choices that considered all these factors, in line with each one’s productive strategy. Among Kutch’s Rabari community, two parganas were mainly involved in the transhumant sheep and goat keeping: Dhebaria Rabari and Vagadia Rabari. Dhebaria Rabari, dwellers of the Anjar taluka, used to stay within Kutch during the monsoon and moved to Sindh, Rajasthan, or central Gujarat once the dry season started. The lower plain of the Indus River, hosting huge pastures, ensured sufficient supply of fodder for the herds throughout the dry season, thus becoming a favored transhumance destination. The Vagadia Rabari, dwellers of the Rapar taluka, used to move towards north Gujarat, where they could find good fodder, water and good migration conditions during winter and summer. Among the Kachhi Rabari, too, shepherds owning large flocks used to migrate towards Sindh, while small herds stayed in western Kutch where the rich forests promised enough forage for the animals all year round. However, these patterns of migration have been constantly evolving in relation with specific events and progressive changes in land use and land tenure systems. We describe here some of the major events and decisions that affected these livelihoods. The India-Pakistan partition of 1947 was a huge blow to the transhumant Rabari community, in that it deeply affected the Rabari who used to migrate to Sindh, mainly from the Dhebaria paragana. Thus, new transhumance routes had to be discovered. They, the Dhebaria Rabari, switched towards eastern Gujarat, moving progressively up to the area around Ahmedabad, towards the South (Anand, Vadodara, and Surat) and then forward, beyond the frontiers of the state. The first migration out of Gujarat happened in 1952, according to Choksi and Dyer (1996) [iii].

What does it mean to be a nomad?

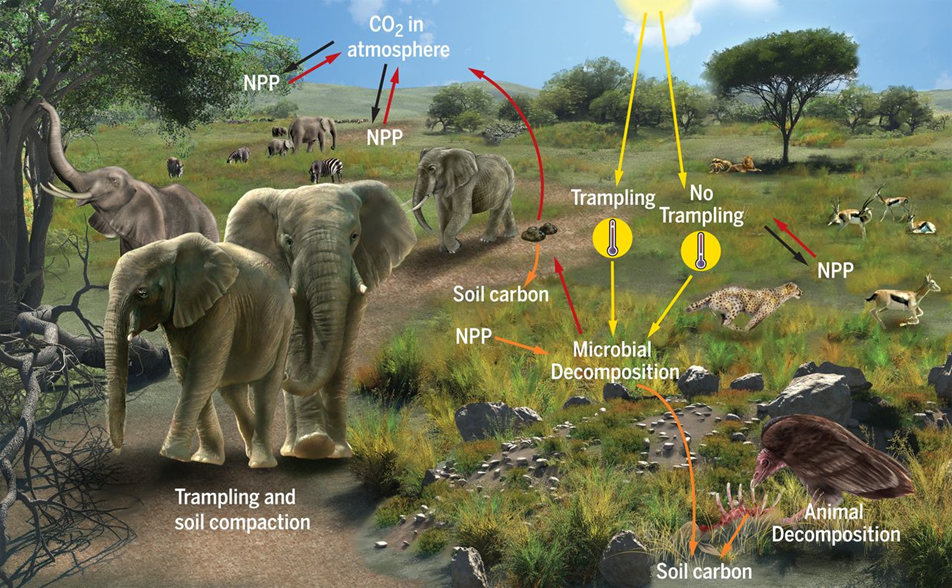

It is not just about the movement of people but also about soil management

One of the most important research findings is that pastoralists in India are increasingly dependent on the use of individual cropping lands for grazing. In the winter and summer seasons, more than 80 per cent of pastoralists in Gujarat graze their livestock on the remains of crops. This number falls to 43 per cent during the monsoon season, but it is still substantial. These findings suggest that the decline of the commons in India has forced pastoralists to rely more on the private lands of farmers than on common grasslands. In the past, the relationship between farmers and pastoralists was purely in-kind—farmers would invite pastoralists to graze on their fields and give them grain in return for milk. As pastoralism declines in India though, this traditional system is rapidly being replaced with Islamic invasion. Under traditional pastoral practices in Gujarat, men were mainly responsible for herding the livestock between grazing lands and women oversaw family and communal finances. However, pastoralists’ increased reliance on monetary transactions, combined with the rise of alternative livelihoods not available to pastoralist women, has led men to take control of the finances in pastoral communities. Most women surveyed indicated that men now undertake most market-related transactions and hold onto the money they receive. As a result, pastoralist women’s role as the primary economic actors in pastoral communities has been greatly diminished.

Meghawal Community

Meghawal community claim to have descended from Rishi Megh, a saint who had the power to bring rain from the clouds through his prayer. The word Meghwar is derived from the Sanskrit words megh, meaning clouds and rain, and war meaning a group, son, and child. The words Meghwal and Meghwar connote a people who belong to Megh lineage [iv].

However, it is theorized that at the time of Muslim invasion of India, many people of high castes including Rajputs, Charans, Brahmins, and Jats joined or were recruited in the Bhambhi caste. Due to this, there came 5 main divisions in the community:

i) The Adu or unmixed Bhambis,

(ii) The Maru Bhambis comprising Rajputs,

(iii) The Charaniya Bhambis including Charans,

(iv) The Bamnia Bhambis comprising Paliwal Brahmins, and

(v) The Jata Bhambis including Jats.

Some Meghwals are associated with other social groups. Shyam Lal Rawat refers to the Meghwals of Rajasthan as “one of the dominating backward castes …”, a connection also made by Debashis Debnath. The Balali and Bunkar communities have also begun using the Meghwal name.

In the past, the relationship between farmers and pastoralists was purely in-kind—farmers would invite pastoralists to graze on their fields and give them grain in return for milk. As pastoralism declines in India though, this traditional system is rapidly being replaced with Islamic invasion. Under traditional pastoral practices in Gujarat, men were mainly responsible for herding the livestock between grazing lands and women oversaw family and communal finances. However, pastoralists’ increased reliance on monetary transactions, combined with the rise of alternative livelihoods not available to pastoralist women, has led men to take control of the finances in pastoral communities. Most women surveyed indicated that men now undertake most market-related transactions and hold onto the money they receive. As a result, pastoralist women’s role as the primary economic actors in pastoral communities has been greatly diminished.

Going beyond Ethno-archaeological Studies to Provide Sustainable future for these Communities

Etic to Emic Approach: Transition from books to field

In anthropological archaeology, one takes up field work to understand the diversity and similarities in cross cultural communities who are still following and preserving their traditional way of living, which could be divided in two different categories- Etic and Emic Approach.

An etic view [v] of a culture is the perspective of an outsider looking in. For example, if an American anthropologist went to Africa to study a nomadic tribe, his/her resulting case study would be from an etic standpoint if he/she did not integrate themselves into the culture they were observing. Some anthropologists may take this approach to avoid altering the culture that they are studying by direct interaction. The etic perspective is data gathering by outsiders that yield questions posed by outsiders. One problem that anthropologists may run in to is that people tend to act differently when they are being observed. It is especially hard for an outsider to gain access to certain private rituals, which may be important for understanding a culture.

An emic view of culture is ultimately a perspective focus on the intrinsic cultural distinctions that are meaningful to the members of a given society, often considered to be an ‘insider’s’ perspective. While this perspective stems from the concept of immersion in a specific culture, the emic participant isn’t always a member of that culture or society. Studies done from an emic perspective can create bias on the part of the participant, especially if said individual is a member of the culture they are studying, thereby failing to keep in mind how their practices are perceived by others and possibly for example indian concept of sahrdaya as explained by Abhinavagupta transcends and includes both these approaches – etic and emic.

Endozoochoric Process and Preserving Soil Erosion in Arid Regions of Gujarat.

Endozoochoric refers to seed dispersal by animal ingestion. It occurs when seeds can pass through the digestive tract of an animal while remaining viable and are thus dispersed away from the parent plant in the animal’s dung. Gravity, wind, or water dispersal may move the small seeds of many crop progenitors with limited success [vi] .

A coherent evolutionary model explaining how the process could have unfolded for these small-seeded annuals. Early plant domestication is primarily a switch from a wild to an anthropogenic dispersal mechanism; therefore, the domestication of millets, chenopods, knotweed, amaranth, and buckwheat represent a switch from endozoochoric to human cultivation. Accompanying this switch, the key characteristics associated with the natural dispersal strategies were lost or reduced, including indigestible seed protections, high levels of dormancy and small seeds. Unlike the large-seeded cereals, the small-seeded grains that mid-Holocene humans targeted often exist today in small fragmentary populations that could not have been effectively harvested due to low plant densities. They also require labour-intensive processing before they can be consumed [vii].

Need to Rethink Pastoralism and Our Future

Need of Involvement of Pastoral Communities for Restoring the Grasslands and Soil Degradation in Gujarat

Indian savanna grasslands are vast extents of grass-dominated landscapes, peppered with some trees, distributed across peninsular India. This biome came into existence 5 to 8 million years ago, although fossil evidence from central India dates grasses back to about 60 million years. Preliminary studies show that about 17% of India’s landmass is covered by savanna grasslands. However, they are poorly understood and consequently undervalued. Grasslands were long believed to be the remains of forests degraded by humans, animals, and natural factors such as fire. These views, entrenched in popular as well as administrative memory, have implications for how grassland landscapes are managed and conserved, with impacts on people and other lifeforms that live and depend on this biome.

Between 1880 and 2010, India lost 26 million hectares of forest land. Widely acknowledged as a crisis, there are several policies, programmes, and judicial pronouncements in place to combat this. During the same time, about 20 million hectares of grasslands were also lost. Somehow this never made it to the front pages. The answer to why this is the case is tangled up in history and economics. For a colonial state that was looking to generate revenue, forests were a natural goldmine. Agricultural land, although not as lucrative, still presented the state with revenues in the form of taxes. These were classified as productive lands. Grasslands, with their nomadic pastoral communities who were hard to pin down and with no obvious income generation capacity, were categorized as ‘wastelands’, a terminology that continues to this day.

The Wasteland Atlas of India declares vast tracts of grassland area as wastelands, seemingly oblivious to its unique and rich natural heritage, and in disregard of the livelihood modes of millions of pastoralists and over 500 million of their livestock. The repercussions of classifying grasslands as forests or as wastelands is that it leaves grasslands open to large-scale diversion to other uses. When treated as a wasteland, grasslands are used as empty spaces to site commercial and development projects, and when treated as an under-achieving forest, it is dug up for afforestation or land improvement programmes, irrevocably modifying the landscape[i].

| “I’ve often been asked what drives me, particularly through the last 50 years of abuse, and ridicule. What has kept me going is one word – care. I care enough about the land, the wildlife, people, the future of humanity. If you care enough, you will do whatever you have to do, no matter what the opposition”. -Allan Savory |

Colonial forest regulations treated grasslands as sub-par forests and pushed for their conversion to tree plantations and irrigated agriculture, while outlawing grazing. This posed a threat to the vast number of species that had adapted over millennia to grasslands, as well as many pastoralist communities that had sustainably used this landscape for their livelihood. Irrigation canals built in these landscapes eventually rendered the soil saline in some areas, rendering them unsuited for agriculture. Continuing to view grasslands through the‘wasteland’ lens, independent India’s land classification norms clubbed all natural habitats under the umbrella of forests, regardless of the type of biome it was. For official purposes, if it wasn’t a forest, it must be made one.

Nomadic pastoralists, with their specialized rotational grazing systems that ensure the measured use of available resources, are constrained to ever-shrinking pockets of grasslands left for their use. Ill-advised planting of trees such as the non-native, Prosopis juliflora, in a bid to render grasslands more productive, have compounded the problem, as the species turned out to be an uncontrollable pest that rapidly spread and encroached grassland areas. The changes to their habitat have negatively impacted grassland-specialist wildlife such as the blackbuck, Great Indian bustard, Lesser florican, and the Indian wolf. Once dominant across the range, many of these species are critically endangered, while others are on the brink of extinction. With new research revealing the substantial potential of grasslands to sequester carbon and combat climate change, the true significance of grassland landscapes can now be conveyed using a vocabulary that policymakers respond to. Unfortunately, old prejudices still stand in the way of this translating to positive political action. Global programmes that aim to reverse land degradation, such as the ambitious Bonn Challenge, are largely tree-plantation drives. During a recent meeting of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification in September 2019, the Indian Prime Minister declared that 26 million hectares of degraded land would be restored by means of additional tree cover by 2030. This is also in tune with India’s climate commitments under the Paris Agreement to create an additional carbon sink of about 3 billion metric tonnes.

References:

[i] The Rabaris: The Nomadic Pastoral Community of Kutch | Sahapedia.

[ii] Dyer, Caroline & Choksi, A. (1996). Research report: An ethnography of literacy acquisition among nomads of Kutch. Compare. 27.

[iii] Ibid. 1996. Pp. 29

[iv] Meghwal – Wikipedia.

[v] Two Views of Culture: Etic & Emic | Cultural Anthropology (lumenlearning.com)

[vi] Spengler, R.N., Mueller, N.G. Grazing animals drove domestication of grain crops. Nat. Plants 5, 656–662 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-019-0470-4.

[vii] https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-019-0470-4.

[vii] India’s Savanna Grasslands: The Unsung Tale | Conservation India

Center for Indic Studies is now on Telegram. For regular updates on Indic Varta, Indic Talks and Indic Courses at CIS, please subscribe to our telegram channel !

- 29 min read

- 0

- 0