- Visitor:13

- Published on:

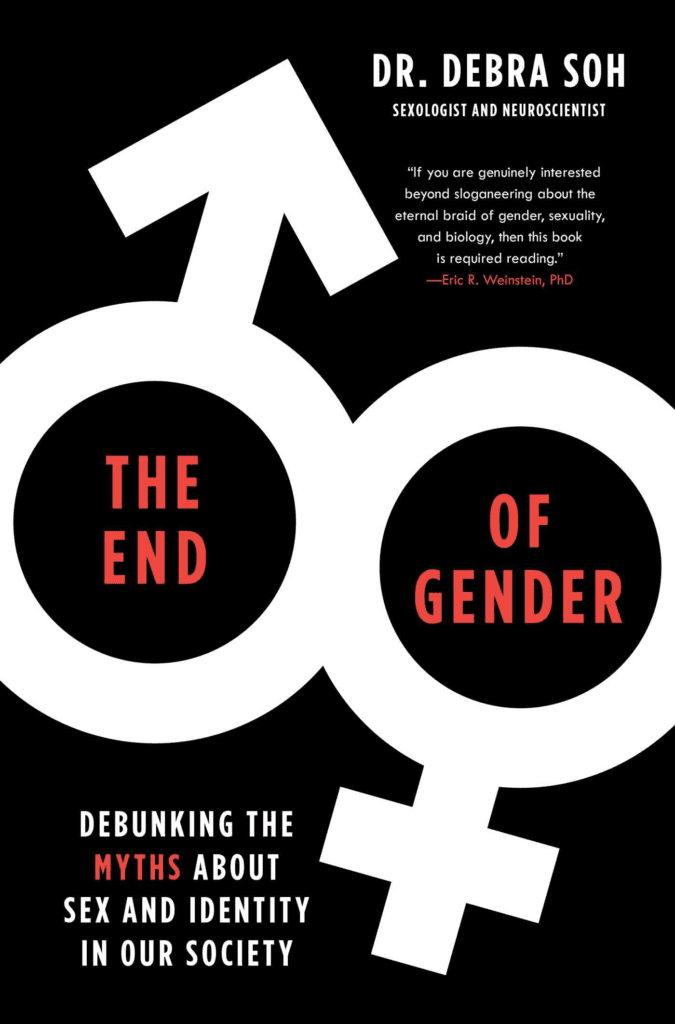

The End of Gender: Debunking the Myths about Sex and Identity in Our Society

The propensity for science denial will always be there, because the truth about who we are is uncomfortable. Opinions are too quickly made based on which side you stand on and what the right answer is for your side. Sometimes we have to take a breath, pull ourselves back, and ask why we believe the things that we do.

- The following piece is the “Concluding” Section of the book titled- “The End of Gender: Debunking the Myths about Sex and Identity in Our Society”. In The End of Gender, neuroscientist and sexologist Dr. Debra Soh uses a research-based approach to address this hot-button topic, unmasking popular misconceptions about the nature vs. nurture debate and exploring what it means to be a woman or a man in today’s society. Both scientific and objective, and drawing on original research and carefully conducted interviews, Soh tackles a wide range of issues, such as gender-neutral parenting, gender dysphoric children, and the neuroscience of being transgender.

I remain close with a number of my sexological colleagues, and at least once a week, I get an email highlighting yet another level of absurdity that my former discipline has reached. My response to these updates is usually shock at how grotesque it’s become, followed by laughter in utter disbelief. Better to laugh than cry, right?

As you now know, social justice has managed to seep beyond the confines of the academic community into the real world. Near the end of my doctoral studies, I received a very kind invitation from an organization asking if I was interested in speaking at an upcoming event. It would include experts from a variety of disciplines, including law and HR, aimed at educating private corporations on issues relating to gender in the workplace.

My talk would be about the science of gender, covering whatever aspects I wanted. Fantastic! I was excited to take my technical skills and use them in an applied setting.

As I began making my slides, I soon saw how many of the topics I wanted to cover were murkier than I had realized. Maybe this was a bad idea. That’s okay, I thought, maintaining my optimism. I’ll find a way to make this work. As I wrapped up my preparation a few days later, my positivity had been hardened by what lay in front of me. I realized that I couldn’t lie, which was surely an indication of what was to come.

The event took place on the top floor of a high-rise, in a brightly painted conference room with gold-flecked pens on every table. I gave my talk, which was straightforward enough. At the end, the organizer opened up the floor for questions. One of the attendees raised her hand. She had a frown on her face. The gist of our conversation went like this:

“Gender is a social construct,” she said.

“No, it isn’t,” I said.

“There are new studies showing no differences between men and women in the brain.” “Those studies are wrong.”

The room suddenly got very quiet. One male employee, who had been poking around on his phone for the entirety of my talk, stopped what he was doing to look up at me.

“Next question,” I said.

A few people asked me to elaborate on some of the animal studies I had mentioned. Then another woman, in a cream-colored pantsuit, bravely put up her hand. Her organization was doing away with the concept of gender and had announced it would be implementing all-gender bathrooms.

“If there is no such thing as gender,” she began, “how do we differentiate between men and women?”

Confused, I asked her to clarify.

“There are some things that are usually associated with being female,” she said. “But if we can’t use the word ‘female,’ how do we refer to them?”

I didn’t know what to tell her. What I wanted to say was, “You refer to them as female, and tell anyone suggesting otherwise to take a hike.” But I inadvertently caught a glance at the organizer, who had this pleading look in her eyes, and not wanting to alienate the other half of the room that wasn’t yet angry at me, I remained speechless. We took a break for lunch. As any graduate student can tell you, the biggest incentive for going anywhere in life is free food. As happy as I was to be getting a paycheck from the event, I was just as delighted to be embarking on an all-you-can-eat feast. It didn’t matter that I had earned the title of “hatemonger” that day. I was going to enjoy the catering. The most curious thing happened next. As I collected my lunch, some members of the audience would pretend they were interested in helping themselves to whichever catering tray I was shoveling food onto my plate from, when really, it was to thank me privately.

“Thank you for saying that,” they would say, before ducking away quickly.

After lunch, things only got worse. The rest of the speakers that day were clearly high on social justice and their interpretation of policies relating to law and medicine were heavily steeped not in science or fact, but activist thinking. The final session of the day consisted of us reading sample vignettes aloud to one another in an attempt to inspire greater authenticity around expressing gender in our lives.

I was reminded of one of my friends, who bought a house a few years earlier, with the goal of renovating it. Within months, he discovered it had a full-blown ant infestation. Anytime I was there paying him a visit, we would spend a good hour stamping out his new little friends. He also showed me, with a weird mix of revulsion and pride, that he had uncovered an entire colony tucked behind the insulation. What appeared, at first glance, to be a healthy wooden frame was in fact housing multiple fervid nests of the queen’s eggs.

Gender ideology reminds me a lot of having an insect problem. It is insidious, popping up in clusters when you least expect it. When it does, you can’t ever get away from it. No matter how many times you try to exterminate the festering, there is another manifestation, lying in wait. These employees would return to their respective companies in the day following the training, and these ideas would continue to permeate.

Sex research conferences, once fertile (I couldn’t help myself) grounds for intellectual inquiry, have already ceded much territory. Conferences are now overrun with preferred pronouns on name cards, anti-oppression workshops, and initiatives catering to “queer” people (never mind that the word “queer” is still considered by many gay people to be a homophobic term of abuse, as we saw in Chapter 3). Plenary talks are predictably infused with feminism. Feminist research methods. Intersectionality in sexual health. Decolonizing sexuality. And just when you thought you were done for the day, conference organizers ensured that social justice activities were planned as evening events.

The trend is also evident in academic research job postings, which seem to place a greater emphasis on whether a potential candidate belongs to the population being studied than their skills as a researcher. Other job postings cite a specific quota that needs to be filled, such as research assistants who identify as nonbinary. It’s almost to the point that a commitment to equity, inclusion, and ticking identity politics boxes is more important than one’s productivity as a scientist.

I worry for the next generation of sex researchers. Those who are more focused on science than activism will self-select out of the field because they recognize how toxic it is becoming. The older generation of scientists, who preferred to focus on the content and quality of their work instead of its political reach, is retiring, only to be replaced by social justice believers. Even after a person has left the field, they aren’t fully free. To this day, I still get lumped into strange conspiracy theories about how sexologists are plotting to eradicate certain communities.

All hope is not lost, however. I do think science will eventually prevail; it may simply take some time before we get there. As I said at the start of this book, the truth can be suppressed, but it will always come out. In the meantime, those of us who have been banished to the wrong side of history have learned a thing or two about maneuvering amid the hysteria (wink, wink). After seeing a number of writers have their books pulled from publication at the hands of activists, I kept very quiet throughout the process of writing this one.

As for those who are still in the academic trenches fighting the good fight, I say, keep going. Don’t apologize for whatever it is you find in your research. In turn, journal editors and reviewers should be firm about which studies are acceptable for publication and which do not deserve to see daylight, instead of caving to activists’ complaints and backpedaling once research findings have been published.

To play devil’s advocate for a moment, must sexology and social justice really be at each other’s throats? Are the two really incompatible, or is there a compromise? Can there exist a middle ground upon which both can be integrated? I do believe scientists owe it to the public to be as transparent and accountable as possible regarding the research they are conducting, and to take feedback from relevant communities into consideration. This would help to neutralize a lot of the animosity and mistrust directed at them from groups that have been discriminated against and exploited in the past. In return, activists should respect the scientific process and have confidence that those who are unethical will be called out by other scientists and disciplined by their institutions.

Experiencing unease, or disliking a particular study’s findings, is not a justification for shutting down the conversation around the issue altogether. As is commonly the case with censorship, attempting to smother dissenting views only makes these views more appealing to impartial onlookers.

For those who say that hateful ideas shouldn’t be entertained and that debating someone you disagree with legitimizes their position, muzzling the debate doesn’t make them go away. Controversial research, in itself, doesn’t pose a threat. Instead of attacking and punishing researchers, we should be combating those who misuse research findings to uphold their prejudicial views.

Of all places, universities should be the strongest proponents of the First Amendment, not enthusiastic supporters of stifling speech and open discussion. Instead, the institutions themselves have been happy to capitulate to the demands of those who have no respect for the academic process or intellectual discourse.

I hope that this book has helped to arm you with facts for the battles you face in your own lives. In time, I don’t doubt that the pendulum will swing back to the center before continuing on toward the opposite extreme. The propensity for science denial will always be there, because the truth about who we are is uncomfortable. Opinions are too quickly made based on which side you stand on and what the right answer is for your side. Sometimes we have to take a breath, pull ourselves back, and ask why we believe the things that we do.

Bibliography:

Soh, Debra. The end of gender: Debunking the myths about sex and identity in our society. Simon and Schuster, 2021.

Center for Indic Studies is now on Telegram. For regular updates on Indic Varta, Indic Talks and Indic Courses at CIS, please subscribe to our telegram channel !

- 6 min read

- 0

- 0