- Visitor:52

- Published on: 2025-11-05 02:28 pm

The Tale of India’s Wandering Storytellers: Guardians of India’s Civilizational Story

These voices, even when faint, still carry the weight of centuries. In every Kavad unfolded, every Baul song drifting through a Bengal field, every Dhadi vaar rising in a gurdwara, a fragment of civilization itself endures. For what is civilization, if not the stories it tells about itself—the itihasa that guides, the songs that console, the lessons that inspire? To let these traditions vanish is to sever our own roots, to forget the mirrors that once showed us who we were and who we could be. Preserving them is not just about protecting an art form; it is about protecting memory, continuity, and the moral compass of civilization. In saving the bards, we save the civilization’s heartbeat.

Picture a village square at dusk. Children gather wide-eyed, elders lean on their walking sticks, and the air hums with anticipation. A lone storyteller steps forward—sometimes with a painted scroll, sometimes with a puppet, sometimes with nothing but his voice—and suddenly the night transforms. Gods descend, demons rise, kings ride into battle, and morals take shape in the hearts of the listeners. For centuries, this was how India remembered itself: not through books or monuments, but through the living breath of stories.

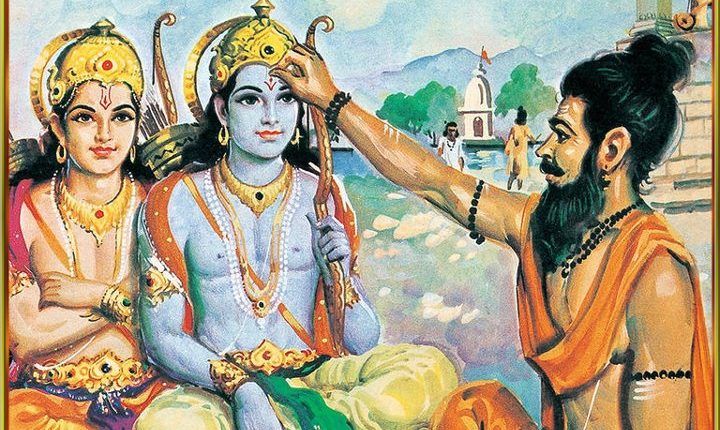

Long before printing presses inked their first page, India’s memory lived in the voices of its storytellers. Around temple courtyards, under banyan trees, and in the glow of oil lamps, bards and minstrels carried entire worlds in their words. These tales were more than stories; they were vessels of dharma, wisdom, and shared identity. Each tale, whether drawn from the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, or a simple folktale of a clever sparrow, was more than entertainment—it was a thread binding generations to civilization's deepest values. The storytellers became guardians of civilization itself—keeping alive epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata, and weaving itihasa, morals, and memory into the fabric of everyday life

At its heart, this article explores how the art of storytelling has preserved India’s cultural soul and moral compass across centuries.

Tracing History: From Vedic Storytellers to Medieval Bards

The story of Indian storytelling is as old as civilization itself. Long before knowledge started being penned down, it travelled on the wings of the spoken word. In every village square and temple courtyard, tales flowed from one generation to the next—not from books, but from voices. Around the 2nd century B.C.E., and even earlier, myths, folktales, and legends rippled across the subcontinent, carried in prose and verse. In the Vedic age, śruti—listening—and smṛti—remembering—were the only pathways to knowledge. A child sitting by the fire would learn not by reading, but by hearing. It was through such listening that the great rivers of the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the five Tamil epics, and the Sangam verses first entered the world—epic poems born of memory, still among the oldest surviving treasures of civilization.

In ancient and medieval India, storytellers carried many roles. They were bards and balladeers, genealogists and praise-poets, entrusted with entertaining audiences while preserving memory and heritage. They entertained, yes—but their deeper role was to safeguard memory. When civilization advanced and the written word grew, stories began to appear in fables and parables. One of the earliest was Vishnu Sharma’s Panchatantra (3rd century B.C.E.), a wondrous blend of prose and verse. Here, animals spoke with human voices, carrying virtues and vices, mirroring society with wit and satire. Each tale closed with wisdom—an ethical jewel passed into the hands of the listener.

During the same time, we get introduced to a distinct class of storytellers—the suta, literally meaning “charioteer.” A suta was no ordinary narrator. As he steered the king’s chariot into battle, he sang of his lord’s ancestors, of past victories and future glory. His voice rose above the thundering hooves, stitching courage into the moment. Over time, other traditions of bardic storytelling flourished. In medieval Rajasthan, Bhats—derived from the Sanskrit word Bhatta, meaning “Lord” or “Scholar”—recounted the glory of Rajput kings, often rewarded with royal donations. Gujarat and Kutch had the Charanas, praise-poets of equal fire, whose verses kept memory alive as much as history itself.

Far to the south, storytelling took on the rhythm of devotion. Known as Kathakalakshepa, this storytelling artform was a spellbinding weave of narration, music, dance, and acting. Performed in temples, at weddings, and in festive gatherings, it demanded not only performance but deep scholarship. The storyteller here was a custodian of Sanskrit texts, yet equally fluent in the local tongue, bridging worlds of scripture and song. Maharashtra’s Powada tradition thundered with heroism. Shahirs sang of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and other warriors, their ballads stirring hearts like the beat of a war-drum.

In the east, the storytellers were known as ‘Kathaks.’ The kathaks—their very name born of katha, meaning story—flourished under the Sena dynasty in Bengal. They blended prose with verse in a style called kathakata, and even today, in pockets of rural Bengal, echoes of that form survive.

Storytelling Forms Across India

Let us delve into various storytelling forms that flourished, survived, and are still practiced in some parts of the country.

In the heart of Rajasthan, the Kavadiya Bhats of Bassi have safeguarded a 400-year-old tradition within a treasure that fits in one’s arms—a Kavad. At first glance it is only a wooden shrine, but when unfolded, it blossoms like a book into painted panels alive with gods, heroes, and age-old legends. Each pathiya is revealed in sequence, while Bhat's voice—rising, falling, rich with gesture—breathes life into the scenes. Devotion mingles with history, myth entwines with moral lessons, and the sacred becomes vividly present. For villages once without temples, the Kavad was both altar and scripture, a travelling sanctuary. Even today, when its doors swing open at festivals, it feels less like a performance and more like memory itself stepping back into the world.

In eastern India, Bengal is home to the Bauls, a community of wandering minstrels whose tradition blends music, mysticism, and philosophy. The Bauls are not merely performers; they are spiritual seekers whose songs articulate themes of love, devotion, and the search for the divine within. Their repertoire, shaped by the teachings of Lalon Fakir and other mystic saints, constitutes a form of oral philosophy expressed through melody. Typically accompanied by simple instruments such as the ektara, dotara, and the duggi drum, Baul performances create a trance-like experience where music functions as both prayer and pedagogy. Even today, in the villages of rural Bengal, one may still encounter groups of Bauls, robes flowing, voices rising like a call from another world.

In Andhra Pradesh, a night with Burra Katha can feel like stepping into a living epic. At the centre stands the Kathakudu, his voice rising above the steady thrum of the burra drum. With sweeping gestures and shifting tones, he spins a blend of myth, history, and sharp social commentary. Two co-performers flank him—drumming, bantering, breaking into dialogue or bursts of humour—keeping the audience enthralled for hours on end. Burra Katha is more than entertainment; it is a people’s theatre. Though passed down orally, it remains vibrantly alive today, a form that continues to educate, provoke, and preserve the folk spirit of Andhra.

In Punjab, history itself becomes song in the voices of Dhadi Jathas. An ensemble of singers, a sarangi player, and the steady beat of the dhadd drum summon the spirit of warriors, saints, and the Gurus’ teachings. Their vaars—heroic ballads—swell and fall like battle cries and prayers woven together. Born in the time of Guru Hargobind, this tradition still electrifies gatherings, gurdwaras, and festivals, carrying centuries of Sikh courage and devotion into the present moment.

And in Tamil Nadu, another form still echoes through temple festivals—the Villupattu, or Bow Song. A great bow, stretched with bells, is plucked as the storyteller chants tales from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and local lore. Percussion, chorus, and gesture weave a spell that can last through the night, sometimes for days. And though centuries old, Villupattu is still alive and lovingly preserved in Tamil temple festivals and cultural gatherings, reminding each generation that tradition continues to sing.

Preserving Civilization’s Heartbeat

With the passing waves of time, the voices of the bards began to thin. Once they stood at the center of kingdoms and village squares, their words binding communities together. But colonialism shifted the tide. Royal courts that once prized poets, singers, and chroniclers dissolved under colonial rule, and with them vanished the patronage that gave bardic communities both livelihood and dignity. Modernization brought new roads, schools, and professions, luring the younger generations away towards the cities. Industrialization, too, altered rhythms of life: machines replaced craft, markets replaced gatherings, and the long nights once devoted to storytelling gave way to the hum of factories and the glow of oil lamps over account books. Later came the printing press, newspapers, cinema, and radio—new storytellers of the modern age, quicker, louder, and more accessible. The bard’s art, woven from patience and memory, began to feel out of step with a world that was running faster. Slowly, like an old song remembered only in fragments, these traditions receded—still present, but no longer the pulse of daily life.

These voices, even when faint, still carry the weight of centuries. In every Kavad unfolded, every Baul song drifting through a Bengal field, every Dhadi vaar rising in a gurdwara, a fragment of civilization itself endures. For what is civilization, if not the stories it tells about itself—the itihasa that guides, the songs that console, the lessons that inspire? To let these traditions vanish is to sever our own roots, to forget the mirrors that once showed us who we were and who we could be. Preserving them is not just about protecting an art form; it is about protecting memory, continuity, and the moral compass of civilization. In saving the bards, we save the civilization’s heartbeat. And as the tides of modern life rush forward, perhaps it is they—the ancient storytellers—who can still teach us how to walk into the future without losing sight of where we began.

References

[1] S. Chandra, Storytellers and the Tradition of Storytelling in India: A Look into the Past and Present, Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.academia.edu/124921548/Storytellers_and_the_Tradition_of_Storytelling_in_India_A_Look_into_the_Past_and_Present

[2] P. Malhotra, “Exploring India’s Folk Storytelling Heritage: Voices Across Time,” Travel + Leisure India & South Asia, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.travelandleisureasia.com/in/people/culture/exploring-indias-folk-storytelling-heritage-voices-across-time/#:~:text=For%20400%20years%2C%20the%20Kavadiya,to%20experience%20rituals%20and%20stories

- 26 min read

- 0

- 0