- Visitor:83

- Published on: 2025-12-08 11:56 am

Aravindan Neelakandan: A Torch-Bearer of the Legacy of Sri Aurobindo

The honour bestowed upon him by Indus University is, therefore, not merely an acknowledgment of past work but a recognition of a lifelong journey, but an āhuti in the great yajña where Aravindan Neelakandan is the yajamāna and the university is the agnihotra. In him, the university celebrates not just a writer or researcher, but a sādhaka of scholarship, someone who has lived the spirit of svādhyāya for decades.

In the quiet coastal light of Tamil Nadu, where the land meets an ancient sea and the memories of ṛṣis seem to rise with the morning mist, the life-journey of Aravindan Neelakandan began like an odyssey that would one day find recognition from all branches of scholarly community just like Ulysses once found upon returning to Ithaca and regaining his throne. The eve of the 10th Convocation of the Indus University has become Ithaca for him by conferring upon him with the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Honoris Causa).

Born in 1971, he emerged from a region where the pulse of tradition is inseparably woven with the rhythms of modernity, a place where the echoes of dharma mingle with the restless aspirations of contemporary India. Over the decades, Aravindan’s life has unfolded like a long, luminous yātrā— sometimes contemplative, sometimes turbulent, sometimes lit by the flame of scholarship and at other times by the heat of activism— but always moving with the certainty of someone walking a path not driven to, but revealed by the divine force. Today, as he is honoured with this degree, the story of his journey appears not merely as a biography but as the unfolding of his sādhana and tapasyā rooted in scholarship, humility, and a relentless commitment to the soul of Bhārata.

Long before his name became familiar in national discourse, long before the debates on identity, geopolitics, and dhārmika continuity shaped his public persona, Aravindan was simply a seeker: quietly attentive to the textures of Indian culture, its philosophical subtlety, its social fractures, and its perennial wisdom. His early academic path may seem unconventional for someone who would later reshape civilizational narratives: a post graduation and an M.Phil. in Economics from Madurai Kamaraj University, along with an M.Sc. in psychology from Madras University. Yet, in retrospect, these disciplines became the two wings of his analytical flight: the economic historian’s structural vision and the psychologist’s insight into the human condition. In them, he found complementary ways of looking at society, culture, and identity, not as abstract theories but as living, breathing processes. This synthesis would later define his writing: empirical without being dry, poetic without losing rigour, passionate without ever surrendering to superficiality.

His entry into public

intellectual life began in an almost serendipitous manner through the early

online magazine Thinnai. In those

days when the Indian internet was still nascent, Thinnai became a meeting ground for voices seeking to articulate

civilizational concerns outside the constrictions of mainstream academia.

Writing for Thinnai introduced him to

Indology, to the emergent debates around science and culture, and to the wide

possibilities of digital discourse. It was there that his pen first took on the

clarity and sharpness that would later define his style which is clear like a

mountain stream and sharp like a chisel carving the outline of forgotten

truths. Every article he wrote became an invocation, an invitation for readers

to step beyond colonial frameworks and rediscover the pulse of Indian

civilization from within.

But writing was only one facet of

his journey. Aravindan was never a scholar content with mere armchair

theorizing. His work took him into the field— into villages, forests, and rural

communities. There, amid the rugged winds of the land’s end, he worked on

cultural conservation and rural development projects. These were not mere

administrative assignments but immersive experiences that deepened his

understanding of Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS), local ecological traditions,

and the enduring wisdom embedded in the daily lives of ordinary people. The

field became his gurukula. The

farmers, artisans, fishermen, and community elders became his teachers,

revealing to him how dharma manifests

not only in texts but in lived practice: in the conservation of water, in

sustainable agriculture, in the preservation of local rituals, in the balance

between artha and ānanda. This interaction with lived

culture gave his later writings a rare authenticity that is rooted, empathetic,

and never alienated from the pulse of the land.

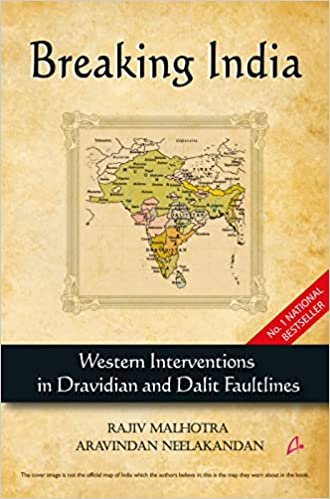

The turning point in his national

prominence came with the publication of Breaking

India in 2011, co-authored with Rajiv Malhotra. More than a bestseller, the

book became a phenomenon— an intellectual earthquake that exposed internal

fault-lines, geopolitical vulnerabilities, and the complex ways in which

external forces intersect with identity politics in India. Breaking India was not merely an academic critique, it was a mirror

held up to society, compelling Indians to confront uncomfortable truths about

fragmentation, manufactured narratives, and civilizational destabilization. The

book was the outcome of rigorous research, wide reading, and a penetrating

insight into cultural psychology. For many, it became a wake-up call. For

Aravindan, it was the moment when his voice entered the national stage. Yet

even after the acclaim, he remained grounded, never treating the book as a

badge of intellectual victory but rather as a dhārmika responsibility that he felt compelled to undertake.

Aravindan’s intellectual

influence deepened in the following years through his prolific writing for Swarajya Magazine, one of the most-read

magazines of our time that writes from the decolonized point-of-view, where he

would go on to publish more than fifty articles on history, Indic thought,

science, identity, and socio-political issues. As a contributing editor, he

shaped not just contents but also the subtlety underneath the conversations by introducing

new frameworks, challenging inherited biases, and illuminating forgotten

corners of Indian history. His essays, whether on ancient astronomy, Dravidian politics,

or the distortions of colonial anthropology, carried a signature blend of

clarity and depth. He wrote as someone who understood that ideas are not

abstractions but forces that shape societies, uplift or distort identities, and

determine the destiny of nations.

Parallel to his editorial responsibilities, his authorship blossomed across genres, languages, and thematic terrains. His book Hindutva: Origin, Evolution and Future (2023), published by BluOne Ink, explored the intellectual genealogy of the term ‘Hindutva’ often debated but seldom understood in its civilizational context. It was a work that wove together historical analysis, philosophical reflection, and sociological insight into a coherent narrative. His later book, A Dharmic Social History of India (2025), expanded this exploration into a grand sweep of Indian cultural evolution, mapping how dharma has shaped social structures, ethical norms, and collective memory across millennia. In these works, one sees the scholar who walks with the ṛṣis across time, listening to the heartbeat of India across centuries.

Yet, even as he authored books of

grand civilizational scope, we must not overlook his works grounded in science,

ecology, and education. His early book, the Wonder

Fern Azolla (2008), co-authored with Dr. Kamalasanan Pillai and endorsed by

Dr. M. S. Swaminathan, reflected his engagement with sustainable agriculture

and ecological innovation. Green

Agricultural Technologies (2013), produced as part of VK-Nardep’s

initiatives, further demonstrated his commitment to combining scientific

innovation with traditional wisdom. His contributions to UNESCO-WaSH projects,

including ‘Conserving Water through Science and Tradition and Renewable Energy:

An Introduction’, revealed a rare confluence of scholarship and grassroots

practicality. These were books written not to impress but to empower; not to

decorate a shelf but to serve a community.

In Tamil literature too, he

carved a unique space for himself. His anthology of science articles titled Kadavulum 40 Hertzm (2002) showcased his

ability to communicate scientific ideas in a language deeply rooted in Tamil

cultural sensibilities. Indhiya Arithal

Muraigal (2015) introduced Tamil readers to Indian Knowledge Systems in a

refreshing, accessible manner. His novelistic explorations, including a

collection of Tamil short stories and the Vedic-philosophical work Aazhi Perithu (2013), revealed a writer

who could traverse genres with ease. From science and anthropology to history

and philosophy— all seem equally at home under his pen.

Then, his versatility extended

further and further. He authored an e-book titled Kashipath (published by Swarajya Magazine in 2019) which is a road

trip travelogue from Bengaluru to Kāśī, capturing the spirit of pilgrimage in

contemporary India. He even produced a C++ programming textbook used in the

SISI Computer Training Academy in the late 1990s. Such breadth is indeed rare—

a scholar who writes on dharma and

geopolitics also producing textbooks on programming languages, a civilizational

thinker who also authors grassroots ecological manuals! It reflects an

integrated view of knowledge, where no domain is foreign, no discipline

isolated, and all learnings ultimately converge toward the upliftment of

society.

As earlier told, Aravindan

contributed significantly to editorial and conceptual projects alongside his

writing. As a Senior Contributing Editor at Swarajya,

he guided narratives, mentored writers, and shaped discourse in subtle, yet

profound ways. His involvement with Vivekananda Kendra by conceptualizing the

sustainable agriculture panels for the Gramodaya Park Exhibition, preparing Patrikas on Vedic wisdom and debunking

the Aryan Invasion Theory, and assisting Michel Danino in his editorial work revealed

his commitment to presenting Indian civilization in truthful, accessible, and

inspiring ways. His role in creating educational content for the Rameshwaram

Green Project under UNICEF-WaSH further underscores his role as a builder, not

merely a commentator—a creator of frameworks that can enrich communities and

institutions.

Across all these domains— civilizational

analysis, historical critique, rural development, ecological advocacy, science

communication, travel writing, fiction, and technological education— Aravindan

Neelakandan emerged as a rare, integrative public intellectual. His voice

became central in debates on Dravidian politics, national identity, historical

distortions, and the recovery of Indic civilizational frameworks. Without

polemics, without the shrillness that often accompanies such debates, he

consistently embodied the principle of satya:

truth sought, truth expressed, truth lived. He stands today as a bridge:

between Tamil intellect and the other think-tanks of India, between tradition

and modernity, between academic scholarship and public discourse, between dharma and contemporary identity.

The honour bestowed upon him by Indus University is, therefore, not merely an acknowledgment of past work but a recognition of a lifelong journey, but an āhuti in the great yajña where Aravindan Neelakandan is the yajamāna and the university is the agnihotra. In him, the university celebrates not just a writer or researcher, but a sādhaka of scholarship, someone who has lived the spirit of svādhyāya for decades. It honours a man whose pen has become a lamp in the labyrinth of modern confusions, whose ideas have helped countless readers rediscover the civilizational essence of Bhārata, and whose life stands as a testimony to what one person can achieve when guided by conviction, humility, and an unwavering commitment to dharma. In his own word

“I come from Tamil Nadu. When we talk about the contribution of individuals to a great work, we always take the example of the squirrel that helped Śrī Rāma to build setu-bandhana… The civilizational building of India has seen great Jāmbuvānas and Hanumānas like in recent times we have Dattopant Thengadi ji, we have Deendayal Upadhyaya, and we have Sri Ram Swarup – such great people! They are the Jāmbuvānas and Hanumānas who have building this setu-bandhana! I just aspire to be squirrel— I am not even a squirrel— I just aspire to be a squirrel and I consider this PhD as the touch of Śrī Rāma on that squirrel.”

As Aravindan received the

Honorary Ph.D. on the wintry evening of 6th December, surrounded by

young graduates stepping into their own futures, he becomes part of their story

as well: a reminder that scholarship is not a destination, but a pilgrimage;

not a monument, but a movement. His journey affirms that the pursuit of

knowledge is itself an offering, a yajña

performed with the flame of inquiry and the devotion of service. And in

honouring him, Indus University honours that eternal spirit of empathic scholarship

which is the heartbeat of the Indian civilization itself!

- 41 min read

- 2

- 0