- Visitor:22

- Published on:

“Experience as the Foundation of Knowledge”. Ayurveda Knowledge System – 2

In this article, P. Ram Manohar explains how Ayurvedic texts takes us on a journey from ignorance to wisdom and finally transcendence to a realm that is beyond all kinds of proof.

Experience – The Foundation of Knowledge

Experience, then is the fountain-spring of all knowledge. Experience can yield wisdom only if one goes into its depths. Otherwise, it does not generate knowledge.

Ayurveda fully endorses the Nyaya-Vaisesika approach in this regard and differentiates between valid and invalid experience known in Sanskrit as Yathartha and AyatharthaAnubhava or Prana and Aprama. Prama means an experience that has been properly measured and aprama means an experience that has not been measured or evaluated properly.

The crux of the matter is that while Veda is experiential, all experience is not Veda. An encounter with reality creates experience but not necessarily knowledge. To transform experience into knowledge, training is required; certainly techniques have to be applied.

The tools of knowledge are called in Sanskrit as Pramanas, literally instruments of measurement. The coalescence of the knower, the tools of knowledge and the objects of knowledge transforms experience into wisdom, Veda.

There is no scope for speculation as a source of knowledge in this scheme. Tarka or speculation is not accepted as a valid means of knowledge (pramana) although it has been assigned a subservient role in the knowledge building enterprise. As a knowledge system, Ayurveda is experiential to the core. A few quotations from the classical texts are illustrative in this regard.

That oil pacifies Vata, Ghi pacifies Pitta and honey pacifies Kapha is a matter of direct observation and experience. It makes no difference if this statement is made by Brahma or his son, states Vag-bhata in his work Astanga-hrdayam.

No matter what arguments one puts forth and what theories one conjures up, the ambasthadi formulation can never exhibit purgative activity, remarks Susrata, pointing out the futility of theorizing without the support of experience.

In another context, Cakrapanidatta refutes the theory that plasma (rasa dhatu) is completely transformed into blood (rakta dhatu), which in turn is converted entirely to flesh (mamsa dhatu) and so on. He points out that if this were the case, a person who fasts for two or three days would become devoid of plasma. This is contrary to experience. So the theory of complete transformation of tissues is not acceptable.

Transforming Experiences in Non-ordinary and Ordinary Modes of Consciousness

In line with the thought of the orthodox knowledge systems of India, Ayurveda postulates that there are basically two methods to transform experience into knowledge. One method is based on nurturing the intuitive faculty and the other on harnessing the rational faculty of the human mind.

Nurturing the intuitive faculty means much more than the occasional flashes of insights that create the ground for exciting discoveries even in the scientific enterprise. In Ayurveda, it means altering the state of consciousness so as to result in a profound and sustained change in perception of reality. All the classical texts of Ayurveda proclaim in unison that the source spring of Ayurvedic knowledge is the realm of non-ordinary modes of consciousness.

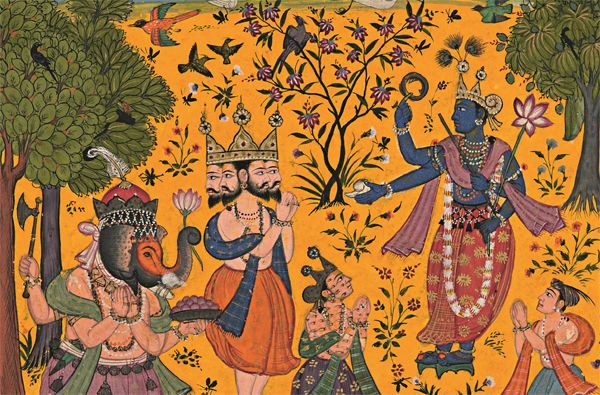

The mythological account of the origins of Ayurveda is an allusion to altered states of consciousness in which the knowledge of Ayurveda is automatically revealed. Brahma, Prajapati, Asvini Devas and Indra, from whom the knowledge of Ayurveda has descended to human beings represent altered states of consciousness which can be evoked in states of meditation. The very word Indra means to know. Indra denotes the human mind that has been awakened by rigorous training. Indra is one who has a thousand eyes (Sahasraksa) because he has profound a hundred Yagas (Satakratu). The gist of the story is that the knowledge of Ayurveda was discovered in an enhanced state of awareness.

Ayurvedic education sought to transform the consciousness of the student so that s/he is established in a higher level of consciousness. Since this involves a transmutation of the mind, a successful student is said to be twice born. To bring about this change, Ayurveda advocates modifications in lifestyle, diet, mental attitude and also the intake of certain medicinal recipes and formulations.

An aspirant who is able to effect this inner transformation gets grounded in the direct experience of the teachings of Ayurveda. If this is not possible, then an understanding of the teachings of Ayurveda that is partly experiential can be obtained by exercising the rational faculty or at least some practical guidelines can be derived that could be applied in real life situations.

Direct perception (pratyaksa) and inference based on perception (anumana) are the two powerful tools of knowledge employed in Ayurveda. Direct perception can be either sensory or supra-sensory. The former operates in the rational realm and the latter in the realm of intuition. Inference bridges the gap between these two kinds of perception. Inference is the understanding of what is invisible by closely observing its relationship with what is visible. It stretches sensory perception to the maximum possible limit. To go beyond inference, one has to operate at the level of supra-sensory perception.

Direct perception operating at the sensory level (Laukika Pratyaksa) and inference based on perception (anumana) constitute the tools to organize the national faculty of the human mind. Direct perception operating at the supra-sensory level (Alaukika pratyaksa) is synonymous with the awakening of the intuitive faculty.

The experiences gained in altered states of consciousness are communicated and preserved through verbal testimony as this realm is accessible only to a select law. Verbal testimony relating such experiences are authoritative and not questioned by people operating at a lower level of awareness. This has often been mistaken as blind belief in authority. Verbal testimony relating to experiences gained in ordinary modes of awareness do not have such an authority and is open to verification through direct perception and inference.

The study of Ayurveda begins with an attempt to understand and appreciate the content of verbal testimony that reports experiences from the realm of supra-sensory perception. This is achieved through an elaborate analysis of the teachings in order to arrive at a proper understanding of their import. This is an attempt to demystify the teachings of Ayurveda. Such an understanding is called Jnana.

The next step is to personally verify the veracity of the teachings. This is not possible to execute with satisfaction in ordinary modes of consciousness. An attempt to understand the import of the teachings and derive guidelines for practical application will facilitate the transformation of consciousness to gain direct experience of the teachings of Ayurveda. This is Pariksa or investigation that culminates in Vijnana or informed experience.

The transition from Jnana to Vijnana takes place through a process of enquiry called as Pariksa. Pariksa means investigation. The ancient teachings encourage investigation and in fact emphasize that Ayurveda can be successfully applied only if its teachings are thoroughly investigated into. Knowledge becomes complete when there is experience or what is understood and understanding of what is experienced. Jnana is understanding and Vijnana is experiencing.

What then is the ultimate proof of knowledge? Is it direct perception. Inference based on perception or verbal testimony? A careful study of the Ayurvedic texts gives one the impression that the journey from ignorance to wisdom starts with a distrust in internal proof, reliance on external proof and finally transcendence to a realm that is beyond all kinds of proof. When mental purity is attained, experience itself becomes the proof. The experience of an individual whose mind is free from rajas (emotional disturbances) and tamas (lack of awareness) is considered to be the ultimate proof of truth.

[Source: P. Ram Manohar, “Ayurveda as a Knowledge System” in Kapil Kapoor and Avadhesh Kumar Singh. eds., Indian Knowledge Systems. Vol.1, (Shimla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study, 2005), pp. 156-170]

Center for Indic Studies is now on Telegram. For regular updates on Indic Varta, Indic Talks and Indic Courses at CIS, please subscribe to our telegram channel !

- 11 min read

- 0

- 0

.jpg)