- Visitor:169

- Published on: 2025-01-09 10:37 am

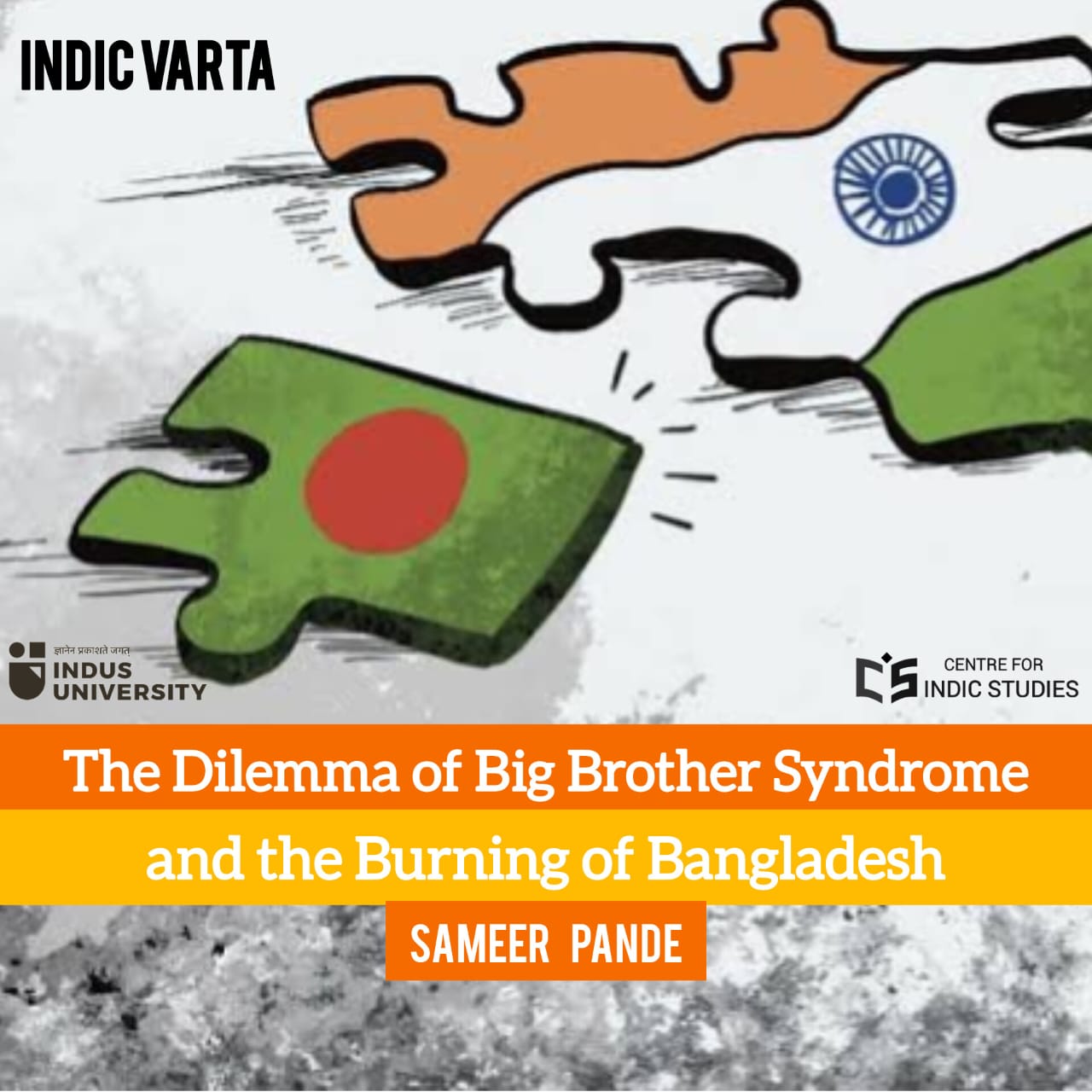

The Dilemma of ‘Big Brother Syndrome’ and the Burning of Bangladesh

The USA uses its own constitution as an extension of world politics. Russia, safeguarding her sovereignty in the historical sanity in the dream of USSR 2.0, boldens the stand day by day. In the name of security and justice, historicity is twisted and turned and retwisted in the global forum by Israel which doesn’t stop it to counterattack its neighboring terrorist groups, and here we are, at the helpless sight of Hindu genocide in Bangladesh despite knowing that it is only Bharat that will care for the safety and security of like-minded and our own people. The question is 'why'— why India is not allowed internally and externally to participate in the South-Asian issues?

Perhaps, the most important question of this time in South-Asian geopolitics is to ask why the head of a state had to flee her own nation? Is there anything that India could do? Would it happen if India would have been ‘Bharat’? Is this the right time to break the shackle of ‘Big Brother Syndrome’ and do what is needed? The important argument is the question to understand why the USA or Russia or Israel take impactful steps going on a full ‘warlike mode’ in international politics. The USA uses its own constitution as an extension of world politics. Russia, safeguarding her sovereignty in the historical sanity in the dream of USSR 2.0, boldens the stand day by day. In the name of security and justice, historicity is twisted and turned and retwisted in the global forum by Israel which doesn’t stop it to counterattack its neighboring terrorist groups, and here we are, at the helpless sight of Hindu genocide in Bangladesh despite knowing that it is only Bharat that will care for the safety and security of like-minded and our own people. The question is ‘why’— why India is not allowed internally and externally to participate in the South-Asian issues? The reason is the narratives set against India and this is the title project ‘Big Brother Syndrome’.

The phenomenon of the ‘Big Brother Syndrome’ has often been used in international relations to describe a situation in which a dominant nation exercises significant influence over its neighbors or less powerful counterparts. This syndrome manifests itself in complex political, economic, and cultural relationships, where the dominant nation is often viewed as both a protector and a bully. In the context of South Asia, the term is often applied to describe India’s role in regional politics, especially as it pertains to its smaller neighbors.

The central question that arises, however, is why, despite its historical, cultural, and geographical proximity to the countries of South Asia, India remains marginalized or constrained in its ability to assert influence or intervene decisively in regional issues, after all she is the motherland of all the South-Asian nations and not because of Britishers rule but counter to that. Why does India, a rising global power, often find itself unable to play a more proactive role in the protection of ethnic and religious minorities, such as the Hindus in Bangladesh? And what does this reveal about the power dynamics of international relations and the constraints placed on India by both internal and external forces?

The ‘Big Brother Syndrome’ is a term used to describe a situation where a larger, more powerful state exerts a paternalistic influence over smaller neighboring states. In this dynamic, the smaller nations may feel the pressure of political, military, and economic control or guidance from the larger power, often resenting it as an imposition on their sovereignty. In a way, the smaller countries are caught between their desire for autonomy and the inevitability of being affected by the policies and actions of their larger neighbor.

The term, when applied to India, refers to the perception held by some smaller South-Asian nations—such as Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Bhutan—that India’s size, power, and historical legacy in the region lead to an overpowering influence in their domestic and foreign policies. This syndrome is complicated by both the benevolent and coercive aspects of India's relationships with these countries. India is often expected to act as a regional leader and protect the security and welfare of its neighbors, but at the same time, it is accused of overstepping its boundaries or using its power in a way that undermines the sovereignty of smaller nations.

India’s Historical and Geopolitical Context

India’s role in South Asia has been shaped by a variety of historical, cultural, and geopolitical factors. Historically, the Indian subcontinent has been a central force in shaping the political and cultural fabric of South Asia. From the Maurya and Gupta empires to the British colonial period, India has long been a dominant power in the region, influencing trade, culture, religion, and governance.

When India gained independence in 1947, the boundaries of the new nation were drawn with little regard for ethnic, cultural, or religious divisions, leaving behind a complex web of political and security challenges. In the decades following independence, India found itself at the crossroads of regional and international politics. As the dominant power in South Asia, India sought to maintain its sovereignty while addressing the security concerns posed by neighboring countries. However, this led to tension with countries that were either wary of Indian dominance or felt that their sovereignty was being undermined by India’s regional assertiveness.

The role of India as the “big brother” in South Asia was cemented during the Cold War when India aligned itself with the Soviet Union, while Pakistan and China sought to align with the West. India’s involvement in the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War, where it supported the creation of Bangladesh and helped defeat Pakistan, is one of the defining moments of its regional influence. However, it also created a narrative of India as a force to be reckoned with in South Asia, leading to both admiration and resentment from neighboring states.

However, for political analysts to understand this, it is imperative to understand the role of the USA, Western academia, and Indian academicians under foreign payroll in the name of scholarship, and that this is the narrative that has constrained Indian influence in the South Asian region.

The Constraints on India’s Regional Engagement

Despite its size, military strength, and economic potential, India faces significant internal and external constraints on its ability to engage actively in South Asian affairs. Externally, these constraints are largely driven by the strategic interests of other global powers, as well as the delicate balance of power within the region.

First comes the influence of major powers and the narratives they set. Both the United States and China, two of the most powerful nations in the world, have significant interests in South Asia, and their strategic engagements often serve to counterbalance India's regional dominance. For instance, the U.S. has forged strong alliances with Pakistan for much of the Cold War and the War on Terror, creating a space where Pakistan could challenge India’s influence. Similarly, China's growing presence in Sri Lanka, Nepal, and the broader Indian Ocean region is seen as a way to counterbalance India’s influence and secure its strategic interests, including access to key maritime routes and resources.

Second is the regional dynamics. The relationships between India and its neighbors are fraught with historical tensions, territorial disputes, and political complexities. For example, India's relationship with Pakistan is heavily influenced by the unresolved Kashmir dispute, leading to a highly charged atmosphere that makes regional cooperation difficult. Likewise, India’s attempts to assert itself in Sri Lanka, Nepal, or Bangladesh often meet resistance due to local political dynamics and the desire for autonomy. Smaller nations in South Asia, while recognizing India’s economic and military strength, often seek to balance this power by fostering relationships with external powers such as China, the USA, or Russia.

Third is the internal political constraints. Internally, India’s policy towards South Asia has been influenced by its own political dynamics, including concerns over minority rights, religious tensions, and ideological divides. There is a considerable domestic constituency that is wary of engaging too aggressively in regional affairs, especially when it comes to issues involving ethnic or religious minorities. For example, India’s government has often been criticized for its failure to act decisively in cases of ethnic or religious violence within neighboring countries, such as the ongoing plight of Hindus in Bangladesh. This political hesitation stems from domestic concerns about fostering tensions within India’s diverse population and the potential repercussions for its internal stability.

And, the fourth is the narratives of Indian intervention. There is also a narrative within South Asia that India is an overbearing neighbor, motivated by its own self-interests rather than a genuine concern for the welfare of its neighbors. These narratives have been created in the name of ‘big brother syndrome’. This perception has been reinforced by a few events such as India’s intervention in Sri Lanka in the 1980s, where its military presence was met with resistance and resentment, but neglecting the welfarism that India does in the region. As a result, any Indian attempt to take a more active role in regional affairs, whether in addressing the plight of minorities or mediating in conflicts, is often viewed with suspicion or outright hostility by other South Asian states.

India and the Question of Hindu Genocide in Bangladesh

One of the most poignant questions in the current geopolitical climate is why India has not taken a stronger stance in the face of the alleged persecution of Hindus in Bangladesh, despite being the natural protector of Hindu minorities in the region. The situation is particularly tragic given India’s shared cultural and historical ties with Bangladesh, as well as the significant Bengali Hindu population that resides in India.

India's apparent inaction can be attributed to a combination of diplomatic considerations, the delicate balance of regional relations, and the fear of inflaming tensions with Bangladesh, which has long been wary of India’s influence. The international community, too, has largely remained silent on the issue, in part due to the global push for stability in South Asia and concerns over the economic and security implications of a more interventionist Indian foreign policy.

This situation highlights the limitations of India’s soft power and the ‘Big Brother Syndrome’. While India may be seen as a natural leader in the region, it is unable to assert itself as a protector of minorities in neighboring countries without risking its own domestic and international standing.

The Need for a New Paradigm: Breaking Free from the Big Brother Syndrome

Historically, Bharat (ancient India) never engaged in imperial or colonial conquests in South Asia or Southeast Asia. Instead, it fostered a model of interconnectedness and mutual enrichment through cultural exchange, trade, and spiritual influence. Unlike European colonial powers, which imposed their rule with coercion and exploitation, the Indian subcontinent’s engagement with its neighbors was characterized by peaceful assimilation and shared values. The spread of Indian culture, language, religion (particularly Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism), and governance systems in regions such as Southeast Asia and Central Asia was largely a result of trade and the voluntary adoption of Indian ideas and practices. Historical records, such as those from ancient Sri Lanka, Thailand, Cambodia, and Indonesia, demonstrate the profound impact of Indian culture, without the exploitation or domination that colonialism entailed. India’s ethical and cultural philosophy, based on non-violence, respect for life, and the concept of Dharma, guided its interactions, making them far more inclusive than coercive or exploitative.

This non-colonial legacy is important to emphasize because it contrasts with the perception of India as a ‘big brother’. India’s regional leadership, far from being one of dominance, is rooted in the principles of mutual respect and cultural exchange, which should be the basis of its engagement with its neighbors today.

Understanding the Colonial Legacy and the Divide and Rule Effect

The colonial period, under British rule, left a lasting psychic and political impact on South Asia. The British implemented the "divide and rule" strategy to fragment regional unity and foster animosity between various ethnic, religious, and cultural groups. This strategy not only weakened the subcontinent but also created lasting divisions that continue to haunt the region. For instance, the British deliberately exacerbated tensions between Hindus and Muslims, while drawing arbitrary borders in the process of partition that created enduring hostilities between India and Pakistan. This colonial-era legacy of division still influences contemporary geopolitics, where India's neighbors sometimes view its regional influence with suspicion, influenced by the historical experiences of British imperialism.

Thus, the ‘Big Brother Syndrome’ in the Indian context, if anyone believes it to be true, is not an intrinsic reflection of the Indic approach, but a byproduct of this colonial legacy. The Indian subcontinent’s history of peaceful coexistence and cultural fluidity is often overshadowed by these colonial-induced narratives of division. These historical wounds need to be healed in order to foster a more accurate and positive image of India as a regional leader, not an imperial overlord.

China's Modern Imperialism: Debt Diplomacy and Economic Coercion

While India faces criticism for the so-called ‘Big Brother Syndrome’, it is important to highlight that it is China, not India, that is the current exponent of imperialism in the South Asian and Southeast Asian regions. Through its debt diplomacy, China is effectively using loans to trap smaller nations into economic dependency. This "debt trap diplomacy" has led countries like Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and several African nations into a cycle of unsustainable debt, where China gains control over critical infrastructure, such as ports and railways, in exchange for financial aid. These practices are reminiscent of the colonial strategies of control through economic dependence, yet they are often dressed up as "welfare" or development aid.

Unlike China’s coercive methods, India’s foreign policy is largely based on voluntary cooperation and mutual benefit. India’s support for regional infrastructure, trade, and development through initiatives such as the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and the India-Bangladesh connectivity projects, is designed to empower neighbors without creating undue dependency. Furthermore, India's diplomatic approach encourages shared growth and respect for sovereignty, in stark contrast to China’s tactics, which often blur the lines between aid and influence.

The below table will help to understand it more:

Conclusion

The perception of India as a ‘big brother’ in South Asia is a narrative rooted more in historical generalizations and contemporary misrepresentations than in India’s actual engagements with its neighbors. While India’s size, economic power, and cultural influence make it a pivotal actor in the region, labeling its efforts as overbearing overlooks the nuanced and collaborative nature of its approach.

India’s contributions—ranging from disaster relief to infrastructure development, and from peacebuilding to regional connectivity—demonstrate its commitment to fostering mutual growth. Unlike coercive models of engagement seen elsewhere, India’s investments are guided by a civilizational ethos that prioritizes respect, co-existence, and shared progress. The deep historical, cultural, and ethical ties India shares with its neighbors underscore its genuine intent to act as a responsible partner, rather than an imposing hegemony.

The so-called “Big Brother Syndrome” often distracts from the constructive role India plays in addressing the region's challenges. While some voices perpetuate this narrative for strategic or political reasons, it is clear that India’s regional engagements aim to empower rather than dominate. For instance, its aid to Bhutan and Nepal focuses on strengthening their sovereignty, and its assistance to crisis-hit nations like Maldives and Sri Lanka underscores a philosophy of solidarity over subjugation.

In contrast, coercive practices by contemporary powers like China highlights the stark difference in approach. Debt diplomacy and strategic encroachments have often led to reduced autonomy for smaller nations, a trajectory that India’s cooperative model consciously avoids. By fostering partnerships based on mutual respect and shared values, India has laid the foundation for a more balanced and inclusive South Asia.

As the region moves forward, India must continue to evolve its narrative from one of dominance to one of collaborative leadership. By addressing colonial legacies, countering misleading perceptions, and championing cooperation, India can redefine its role in South Asia as a beacon of hope and progress. This reimagined paradigm will not only strengthen regional ties but also showcase India as a leader whose rise benefits not just itself but the entire region, united by a shared vision of prosperity and peace.

- 84 min read

- 6

- 0