- Visitor:30

- Published on:

The Problem with the Welfare State

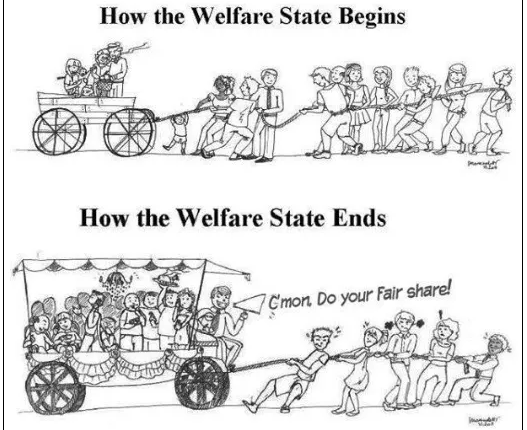

This is an excerpt from the book “Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010” by Charles Murray. The book gives two models of society: the American Project and The European Welfare State. The author makes a critique of the Welfare State of Europe, analyzing its inherent unsustainability and internal faults and presents another alternative model which is hinged equally on responsibilities and rights.

The European model assumes that human needs can be disaggregated when it comes to choices about public policy. People need food and shelter, so let us make sure that everyone has food and shelter. People may also need self-respect, but that doesn’t have anything to do with whether the state provides them with food and shelter. People may also need intimate relationships with others, but that doesn’t have anything to do with policies regarding marriage and children. People may also need self-actualization, but that doesn’t have anything to do with policies that diminish the challenges of life.

Shelter are all that count. But in an advanced society, the needs for food and shelter can be met in a variety of ways, and at that point human needs can no longer be disaggregated. The ways in which food and shelter are obtained affects whether the other human needs are met.

People need self-respect, but self-respect must be earned – it cannot be self-respect if it’s not earned – and the only way to earn anything is to achieve it in the face of the possibility of failing. People need intimate relationships with others, but intimate relationships that are rich and fulfilling need content, and that content is supplied only when humans are engaged in interactions that have consequences.

People need self-actualization, but self-actualization is not a straight road, visible in advance, running from point A to point B. Self-actualization intrinsically requires an exploration of possibilities for life beyond the obvious and convenient. All of these good things in life – self-respect, intimate relationships, and self-actualization – require freedom in the only way that freedom is meaningful; freedom to act in all arenas of life coupled with responsibility for the consequences of those actions. The underlying meaning of that coupling – freedom and responsibility – is crucial. Responsibility for the consequences of actions is not the price of freedom, but one of its rewards. Knowing that we have responsibility for the consequences of our actions is a major part of what makes life worth living.

The four domains that, I argue, are the sources of deep satisfactions are: family, vocation, community, and faith. In each of those domains, responsibility for the desired outcome is inseparable from the satisfaction. The deep satisfactions that go with raising children arise from having fulfilled your responsibility for just about the most important thing that human beings do. If you’re a disengaged father who doesn’t contribute much to that effort, or a wealthy mother who has turned over most of the hard part to full-time day care and then boarding schools, the satisfactions are diminished accordingly. The same is true if you’re a low-income parent who finds it easier to let the apparatus of an advanced welfare state take over.

In the workplace, getting a pay raise is pleasant whether you deserve it or not, but the deep satisfactions that can come from a job promotion are inextricably bound up with the sense of having done things that merited it. If you know that you got the promotion just because you’re the boss’s nephew, or because the civil service rules specify that you must get that promotion if you have served enough time in grade, deep satisfactions are impossible.

When the government intervenes to help, whether in the European welfare state or in America’s more diluted version, it not only diminishes our responsibility for the desired outcome, it enfeebles the institutions through which people live satisfying lives. There is no way for clever planners to avoid it.

Marriage is a strong and vital institution not because the day-to-day work of raising children and being a good spouse is so much fun, but because the family has responsibility for doing important things that won’t get done unless the family does them. Communities are strong and vital not because it’s so much fun to respond to our neighbors’ needs, but because the community has the responsibility for doing important things that won’t get done unless the community does them.

Once that imperative has been met – family and community really do have the action – then an elaborate web of expectations, rewards, and punishments evolves over time. Together, that web leads to norms of good behavior that support families and communities in performing their functions. When the government says it will take some of the trouble out of doing the things that families and communities evolved to do, it inevitably takes some of the action away from families and communities. The web frays, and eventually disintegrates.

Through November 21, 1963, the American project demonstrated that a society can provide great personal freedom while generating strong and vital human networks that helped its citizens cope. America on the eve of John Kennedy’s assassination, while flawed, was still headed in the right direction.

In some ways, the United States continued in the right direction, bringing us closer to the ideals that animated the nation’s creation. The leading examples are the revolutions in the status of African Americans and women. The barriers facing them in 1963 represented a continuing failure of America to make good on its ideals. In every realm of American life, those barriers had been reduced drastically by 2010.

In other ways, it has been downhill ever since. Family, vocation, community, and faith have all been enfeebled, in predictable ways.

The problems these changes have engendered are different in kind from the problems of poverty. The problems that children suffer because of poverty disappear when the family is no longer poor. The problems that poor communities suffer because of poverty disappear when the community is no longer poor. The first two thirds of the twentieth century saw spectacular progress on that front. But when families become dysfunctional, or cease to form altogether, growing numbers of children suffer in ways that have little to do with lack of money. When communities are no longer bound by their member’s web of mutual obligations, the continuing human needs must be handed over to bureaucracies – the bluntest, clumsiest of all tools for giving people the kind of help they need. The neighborhood becomes a sterile place to live at best and, at worst, becomes the Hobbesian all-against-all-free-fire zone that we have seen in some of our major cities.

These costs – enfeebling family, vocation, community, and faith – are not exacted on the people of Belmont (a rich neighborhood in America). The things the government does to take the trouble out of things seldom intersect with the life of a successful attorney or executive. Rather, they intersect with life in Fishtown (a poor neighborhood in America).

A man who is holding down a menial job and thereby supporting a wife and children is doing something authentically important with his life. He should take deep satisfaction from that, and be praised by his community for doing so. If that same man lives under a system that says the children of the woman he sleeps with will be taken care of whether or not he contributes, then that status goes away. I am not describing a theoretical outcome, but American neighborhoods where, once, working at a menial job to provide for his family made a man proud and gave him status in his community, and where now it doesn’t. Taking the trouble out of life strips people of major ways in which human beings look back on their lives and say, “I made a difference.”

Europe has proved that countries with enfeebled family, vocation, community, and faith can still be pleasant places to live. I am delighted when I get a chance to go to Stockholm or Paris. When I get there, the people don’t seem to be groaning under the yoke of an oppressive system. On the contrary, there’s a lot to like about day-to-day life in the advanced welfare states of western Europe. They are great places to visit.

But the view of life that has taken root in those same countries is problematic. It seems to go something like this: The purpose of life is to while away the time between birth and death as pleasantly as possible, and the purpose of government is to make it as easy as possible to while away the time as pleasantly as possible – the Europe Syndrome.

Europe’s short workweeks and frequent vacations are one symptom of the syndrome. The idea of work as a means of self-actualization has faded. The view of work as a necessary evil, interfering with the higher good of leisure, dominates. To have to go out to look for a job or to have to risk being fired from a job are seen as terrible impositions. The precipitous decline of marriage, far greater in Europe than in the United States, is another symptom. What is the point of a life-time commitment when the state will act as surrogate spouse when it comes to paying the bills?

The decline of fertility to far below replacement is another symptom. Children are seen as a burden that the state must help shoulder and even then they’re a lot of trouble that distract from things that are more fun. The secularization of Europe is yet another symptom. Europeans have broadly come to believe that humans are a collection of activated chemicals that, after a period of time, deactivate. If that’s the case, saying that the purpose of life is to pass the time as pleasantly as possible is a reasonable position. Indeed, taking any other position is ultimately irrational.

The alternative to the Europe Syndrome is to say that your life can have transcendent meaning if it is spent doing important things – raising a family, supporting yourself, being a good friend and a good neighbor, learning what you can do well and then doing it as well as you possibly can. Providing the best possible framework for doing those things is what the American project is all about. When I say that the American project is in danger, that’s the nature of the loss I have in mind; the loss of the framework through which people can best pursue happiness.

The reasons we face the prospect of losing that heritage are many, but none are more important than the twin realities that I have tried to describe in the preceding chapters. On one side of the spectrum, a significant and growing portion of the American population is losing the virtues required to be functioning members of a free society. On the other side of the spectrum, the people who run the country are doing just fine. Their framework for pursuing happiness is relatively unaffected by the forces that are enfeebling family, community, vocation, and faith elsewhere in the society. In fact, they have become so isolated that they are often oblivious to the nature of the problems that exist elsewhere.

The forces that have led to the formation of the new lower class continue as I write. In the absence of some outside intervention, the new lower class will continue to grow. Advocacy for that outside intervention can come from many levels of society – that much is still true in America. But eventually it must gain the support of the new upper class if it is to be ratified. Too much power is held by the new upper class to expect otherwise.

- 15 min read

- 0

- 0