- Visitor:177

- Published on:

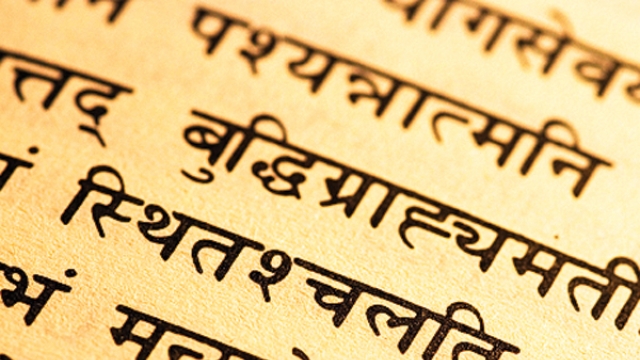

Caste System and Brahmins: The biggest hurdles for Missionaries to convert Hindus

The vast amount of missionary literature and correspondence, prior to 1857, mentions two hurdles in the path of religious conversion. •The first hurdle was the stringent regulations of the caste system due to which the converted person was ostracized by the caste and community to which he belonged. •The second hurdle was the immense respect and reverence in the society for Brahmins. The missionaries found themselves unable to challenge the moral and intellectual superiority of the Brahmins.

Christian missionaries have played a major role in shaping our current perspective of the caste system. The singular objective of the missionaries has been the religious conversion of natives, ever since the Portuguese arrived in India in 1498, and the biggest hurdle faced by the missionaries has been the caste system.

The vast amount of missionary literature and correspondence, prior to 1857, mentions two hurdles in the path of religious conversion.

The first hurdle was the stringent regulations of the caste system due to which the converted person was ostracized by the caste and community to which he belonged. The converted person would also lose the right to his ancestral property and business, hence he would become socially and financially destitute.

The second hurdle was the immense respect and reverence in society for Brahmins. The missionaries found themselves unable to challenge the moral and intellectual superiority of the Brahmins. Due to this experience, the primary declared goal of the missionaries was now to dismantle the ‘Brahmin-designed’ caste system. In the name of freeing people from the shackles of caste, the missionaries focused their efforts on the so-called poor and lower castes.

The attempts of religious conversion may be broadly divided into four time periods. First, the attempts made by Portugese and Jesuit missionaries in the sixteenth century. The Portuguese challenged the totalitarian rule of Muslims in the western coast of India. The local fishermen community that was settled in the Portuguese controlled areas on the western coast was perhaps induced to convert so that they could receive protection from the Portuguese. Since the entire community converted to Christianity, there was no fear among individuals about losing their caste.

The fate of the Portuguese empire was sealed when, in 1542, after the arrival of St. Xavier, political force was used to convert the upper caste people as well. In order to bring people from influential classes into the fold of Christianity, Robert De Nobili arrived in India in 1606. Sporting a tilak, janeyu, shikha and dressing up like a Brahmin, Robert De Nobili proclaimed himself to be a ‘Jesuit Brahmin’. He did not allow even the shadow of lower caste converts to come near him. Despite all these efforts, De Nobili was not successful.

A century later, in 1706, protestant missionaries from Denmark set up a missionary center in Tranquebar (now Tharangambadi) on the eastern coast of India. Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg, the head of this center, realized that no religious conversions could take place if the caste system was disturbed. So, he adopted the earlier Portuguese strategy of converting entire communities while keeping the caste system intact. Ziegenbalg was himself quite impressed by the caste system, because of which he was often reprimanded by the headquarters in Denmark. In the coming years, Father Schwarz is believed to have made a significant contribution in the religious conversion initiatives of the Tranquebar mission but even he approved of the caste system within the Church.

So, by the beginning of the eighteenth century, before the establishment of British rule in India, missionary efforts were limited to South India. While the Danish protestant mission was present on the eastern coast, the western coast had the Roman Catholic Church. When British gained strong foothold in the Bengal, the Bishop of Salisbury, under the influence of officials like Charles Grant, wrote an appeal to the Governor General Lord Cornwallis who replied on 27 December, 1788.

In his reply, Cornwallis noted that “the religious conversion of Hindus is almost impossible because of the fear of losing their caste, and as far as the question of the paltry success achieved by the Portuguese missionaries of Malabar is concerned, their example is neither inspiring nor encouraging because the people converted by the Portuguese are considered to be among the poorest and most disdainful lot. Even after three centuries, the converted people have neither able to free themselves from the caste system nor have they made any intellectual progress. In the nineteenth century, Father Caldwell described the pitiable condition of these converts in the following words: “in their habits, intellect and morality, they are no different from the idol worshipping non-Christians”.

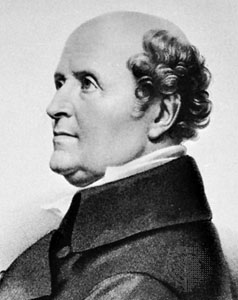

The fact that two contemporary Christian missionary perspectives on caste can be starkly different is best illustrated by the contrasting accounts of Protestant Baptist missionary William Ward and French Roman Catholic missionary Abbe Dubois. Incidentally, both arrived in India in the same year, 1793, and, until 1823, both had spent nearly 31 years in India. While William Ward worked in Bengal, Abbe Dubois spent most of his time in the southern Indian cities of Pondicherry and Mysore. Although both Ward and Dubois lived in India and studied the caste system during the same period, their inferences about caste were poles apart.

Ward’s work, published in 1812, is a scathing criticism of the caste system which is blamed as the singular reason for the degradation of Hindu society. The eradication of caste is declared as the goal of Christian missionaries.

Whereas, Abbe Dubois has immensely appreciated the caste system. In Dubois’ view, the caste system provides financial and social security to each individual and offers everyone an opportunity to pursue their life journey in harmony with their interests and natural inclinations. The lengthy letters sent by Dubois to France in 1825 make it amply clear that Indians are far more morally superior to us and their religious conversion is neither necessary nor possible.

Whereas, the picture of Hindu society that emerges from the four sections of William Ward’s treatise is completely contrary to Dubois’ view. Ward concluded that the religious conversion of Hindus is imperative in order to uplift them from the abyss of moral degradation.

Both Ward and Dubois explained the reasons for the publicity of the East India Company in their essays of 1805. But while the East India Company kept Dubois’ essay under the wraps for a long time, the Company immediately published the essay of Ward. As a result, Ward’s perspective which had the support of British rule, was adopted by the Protestant Christian missionaries working for the cause of religious conversion. But they were faced with a question: Is religious conversion possible by attacking the caste system? What is our goal: to dismantle the caste system or religious conversion? How are these questions answered in the interesting debates of the nineteenth century?

[Navbharat Times, 26 October, 1995]

Translated from Hindi by Ankur Kakkar

- 88 min read

- 2

- 0