- Visitor:47

- Published on: 2025-07-29 04:30 pm

As Many Branches, So Many Trees: An Aspect of Indian Knowledge System

IKS never demanded uniformity. Charvaka’s materialism coexisted with Shankara’s idealism; Tantra’s embodied spirituality contrasted with Advaita’s transcendence. This was not mere tolerance but an active engagement with difference—a recognition that reality is too vast for any one system to monopolize.

Man has always been in pursuit of the essence of things—something which, if truly known, reveals the full picture, leaving nothing hidden. For instance, we attempt to understand the human being through certain epistemic categories such as rationality, emotionality, or spirituality, among others. Now, if one accepts this way of knowing reality—through its essence—can we also offer a window of opportunity to grasp the spirit of an originating cultural movement like the Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS)? Affirmatively put, we can argue that the idea behind the phrase "Quot Rami, Tot Arbores"—"As Many Branches, So Many Trees"—though Latin in origin—resonates deeply with the pluralistic and dialectical heart of IKS. Interestingly, this very idea has been embraced by Allahabad University in its Sanskrit rendering as well as its official slogan: Yavatyah shakhah tavanto vrikshah, capturing the inclusive, interrogative, and multifaceted spirit of its culture—and implicitly conveying much about the richness and depth of the Indian intellectual tradition. It reflects a civilization where wisdom is not a singular trunk but a vast, branching forest—each tree distinct, yet nourished by the same soil of inquiry. At the core of IKS lies an interrogative spirit, a tradition where questioning is sacred, dissent is generative, and truth is not a fixed doctrine but a living dialogue.

The essence of IKS—its argumentative, inclusive, and liberating nature—makes it not just a repository of ancient wisdom but a dynamic framework for engaging with knowledge itself. Amartya Sen’s The Argumentative Indian was more than a title—it was a recognition of a civilizational temperament. From the Upanishadic sages who framed wisdom as prashnottara (question-and-answer) to the Shastrarthas (philosophical debates) of medieval scholars, India’s intellectual history is rich enough of contested ideas. The Nyaya school elevated logic (tarka) to a spiritual discipline, while Jain Anekantavada insisted that truth is multifaceted. Even the Bhagavad Gita, often seen as a sermon, begins with Arjuna’s doubt—a crisis that Krishna resolves not by silencing him but by engaging his reasoning. This culture of questioning is vividly illustrated in two foundational Indian texts that mirror each other in striking yet complementary ways. In the Bhagavad Gita, it is the everyday man—a kshatriya, Arjuna—who, gripped by existential despair (vishada), turns to Keshava, the divine guide, Lord Krishna, seeking clarity and direction. Here, the human seeks truth from the divine.

Yet in the Yogavasishtha, also known as Mokshopaya, the roles are reversed: it is Lord Rama, an avatara of Vishnu himself, who is overwhelmed by a deep philosophical nihilism and turns to the sage Vasistha for answers. Vasistha, a human rishi, attained wisdom through esoteric practices and inner realization. These two narratives—one where the man seeks from God, the other where God seeks from man—encapsulate a uniquely Indian view: that the interrogative spirit transcends hierarchy, and that divine and human are bound by the same quest for liberation. In this culture, to question is not to defy but to dignify the pursuit of truth, whether one is a king, a sage, or a god.

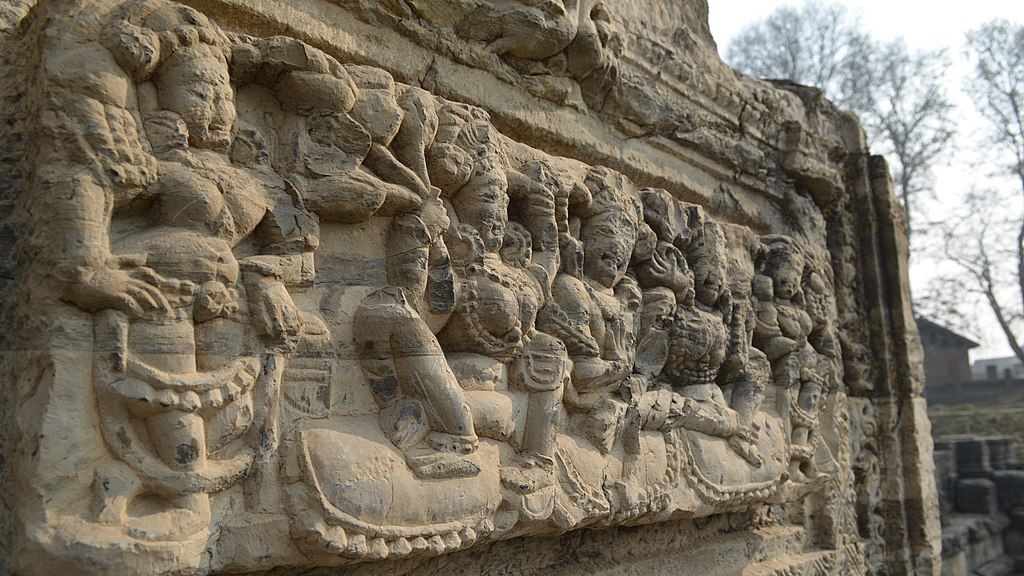

This culture of questioning was institutionalized. Buddhist Kathāvatthu texts formalized debate rules; Adi Shankara’s victories in philosophical disputes were celebrated not as conquests but as clarifications. Unlike dogmatic traditions that fear dissent, IKS treated opposition as a refining fire—Purva-Paksha (the opponent’s view) was rigorously studied before being rebutted. The goal was not to "win" but to liberate them from petty confinements of egoity, by peeling away ignorance through dialogue. That is why we are of the view that the Latin "Quot Rami, Tot Arbores" finds its Indian parallel in the Rigvedic declaration: "Ekam Sat Vipra Bahudha Vadanti" (Truth is One, the Wise Call it by Many Names). IKS never demanded uniformity. Charvaka’s materialism coexisted with Shankara’s idealism; Tantra’s embodied spirituality contrasted with Advaita’s transcendence. This was not mere tolerance but an active engagement with difference—a recognition that reality is too vast for any one system to monopolize. Consider the Darshanas (schools of philosophy): Nyaya (logic) and Vaisheshika (atomism) sought empirical precision; Samkhya’s dualism and Yoga’s discipline addressed the mind-body problem; Mimamsa’s ritual focus and Vedanta’s metaphysical unity represented divergent paths to the sacred. These were not isolated silos but interconnected debates, where one school’s weakness spurred another’s innovation. The Jain Syadvada (theory of conditional predication)—"in some ways, it is; in some ways, it is not"—epitomized this humility, insisting that all claims are context-bound.

The ultimate aim of Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS) has always been freedom. However, the nature of this freedom is a matter of philosophical inquiry. Unlike traditions that equate liberation with passive acceptance, Indian thinkers viewed it as an awakening through critique. The Buddha’s injunction to "ehi passiko" (come and see) rejected blind faith; Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka dialectics deconstructed all rigid views to reveal middle-way wisdom. Even the Bhakti movement’s devotional fervor was often subversive, with saints like Kabir and Basava challenging caste orthodoxy through poetry. This anti-authoritarian streak extended to governance. Kautilya’s Arthashastra blended realpolitik with welfare economics, while Ashoka’s edicts preached tolerance not as weakness but as statecraft. In science, Aryabhatta’s heliocentrism and Sushruta’s surgical innovations emerged from empirical rigor, not scriptural decree.

Today, as societies grapple with polarization and cultural erasure, IKS offers a model for intellectual pluralism. Its spirit counters both fundamentalism and shallow relativism by insisting that truth is discovered through engaged diversity—a dialogue where traditions interrogate one another without seeking annihilation. To embrace IKS is not to romanticize the past but to reactivate its interrogative energy. Whether in education (reviving Gurukula dialogue models), science (integrating Yukti with modern methods), or ethics (applying Dharma’s contextual wisdom), the task is to nurture new "branches" while staying rooted in critical inquiry. The spirit of IKS can be distilled into a call to action : "Know by Questioning, Grow by Arguing, Flourish by Including." This is not a slogan of nostalgia but a blueprint for the future—a reminder that the deepest knowledge systems are those that remain open, adaptive, and forever unfinished. In a world rushing to simplistic answers, India’s greatest gift may be its ancient, audacious habit of doubt: the courage to see forests where others see only trees. Yet, it is also a matter of fact that while doubt is considered healthy, Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS), whether followed by spiritualists or materialists, do not permit anartha (meaningless or purposeless speculation) in place of artha (meaningful inquiry). IKS employs its own methodologies and logical frameworks, rooted in discipline and precision. As noted , one of the most prominent methods of inquiry in IKS is vada—structured, reasoned debate. It operates on the understanding that while questioning is encouraged, it must be purposeful and grounded; one cannot grow a mango on a babul (thorn) tree. In other words, fruitful outcomes arise only from fertile grounds of sincere, methodical engagement.

- 23 min read

- 2

- 0