- Visitor:225

- Published on:

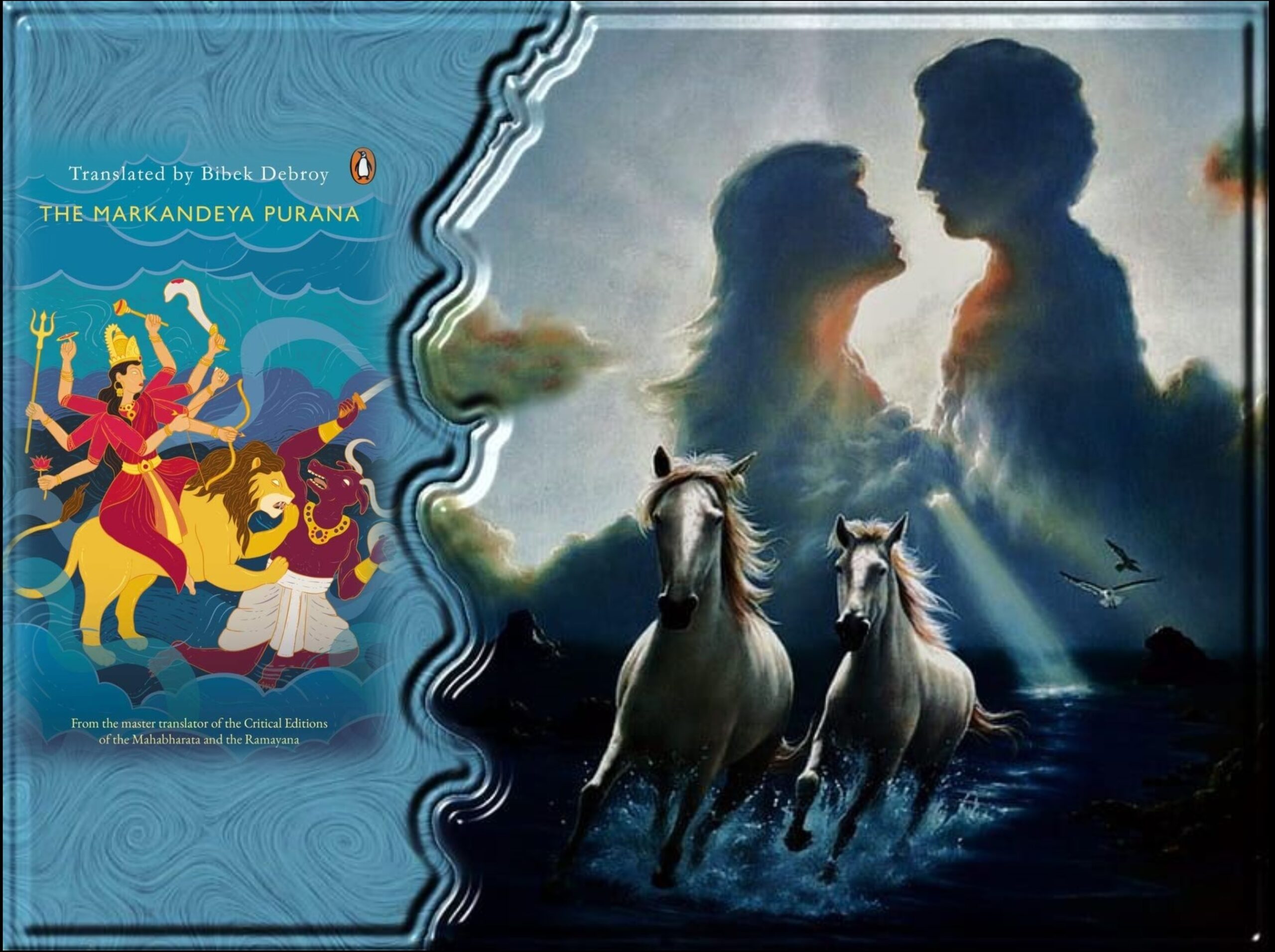

Aesthetics of Indian Art

This is an excerpt from the “Human and Divine: 2000 Years of Indian Sculpture” by Balraj Khanna and George Michell. Balraj Khanna in this short excerpt discusses the aesthetics of Indian Art. He explores the symbolism of Indian art. Why is it not physically accurate about anatomy like the Greek art? Why does it focus on facial expressions favoring inner peace? It gives a basic understanding about the spiritual import behind creating Hindu art.

Well defined aesthetic ideas were assembled in a fourth century AD treatise on dramaturgy, entitled Natyasastra and ascribed to Bharata, containing guidelines for natya (drama), dance and music. This aesthetic theory was applicable to other arts as well, especially sculpture which has a natural affinity with dance.

The Natyashastra crystallized Indian aesthetic thought, laying down rules for creative expression which had to be followed strictly. Every work was required in an unselfconscious way to exude a certain special flavor or rasa – a Sanskrit word in daily use in contemporary India meaning juice (like that of a fruit) – to arouse in the beholder the desired response, bhava. Bharata’s book carried a list and commentaries on most notable rasas which was extended by later thinkers, but the following five with their linking bhavas have been of particular relevance to the development of Indian sculpture:

- Shringara (the delightful or the erotic) – rati (love)

- Rudra (the furious) – Krodha (anger)

- Bhayanka (the terrible, frightening) – bhaya (fear)

- Vira (the heroic or the valiant) – utsaha (energy)

- Shanta (the peaceful) – shama (tranquility)

Historically, the Shringara rasa has been the most popular, reflecting the innate need of the Indian psyche to celebrate the gift of life, so lavishly and poetically illustrated by Indian sculpture, as well as literature, dance and painting.

A later text, the anonymous Shilpashastra, gave instructions for sculptors concerning the practicalities of their craft. It showed them how best to achieve a balance between concave and convex forms, between positive and negative shapes. Similarly, Shilpashastra offered guidance on the right translation of body language into expressive movement. It emphasized certain mudras (gestures made by hands and fingers) and figure groupings – inspired by dance and drama – to convey the desired dramatic effect.

Facial expression was considered of the utmost importance. Godly figures had to radiate serenity and total calm, a hallmark of Indian sculpture, achievable only by sculptors who themselves were calm. Thus, the gods are always looking beyond human life – we can never meet their gaze because it is always focused inward, the reservoir of tranquility.

Verisimilitude to life was not the sculptor’s concern. What he was expected to depict was a certain chosen rasa that a figure or a group of figures was to excite. Also, anatomical detail, such as musculature, was not observed accurately in Indian sculpture, the transcendental aspect of the figure being more important than its perceptible properties.

When a Yogi (Yoga mean Yoking, i.e., the mind to God) sat down to meditate, he took a deep breath – prana (breath of life) – filling his chest and then exhaling slowly. Performed repeatedly, this exercise intensified the concentration of the mind, making the yoking of it to the source of prana, God, more easily achievable. It was the sculptor’s aim to capture the moment when a yogi, say a Jain divinity, sat in the upright lotus position, his waist narrow and his chest slightly expanded because it held the prana. The sculptor could do this because he himself had experienced that moment and therefore knew how it felt to be in that state when the prana was drawn in.

Sculpture in India has a very different meaning to that of the West. Traditionally, it did not have a civic role to play, nor was it created to satisfy aesthetic curiosity. That it is now on view in museum all over India – and enjoyed, too – was largely due to a British convention, established in the nineteenth century during the heyday of the Raj.

Indian sculpture has always occupied a special, private place within people’s hearts. It radiates reassurance, compassion and love, fulfilling the inner need to be in tune with a higher power. Most Indians are well-versed in the elaborate who’s who of their religion. Hindus know what every god and goddess personifies and what rasa he or she emanates in whichever form they are presented in sculpture or painting. Some they know so well that they can communicate with them on a person-to-person basis, as with a close friend. And, typically, in devotional India, they know in their hearts that this is not a one-sided relationship.

The Hindu Holy Trinity is composed of the gods Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. Every Hindu knows why Shiva wears a live cobra as a necklace (he tamed all nature’s forces), or why Vishnu, embodying heroism, vira, has four arms (they suggest his superhuman prowess) and Brahma four heads (so that he can see in all four directions at once). The highly incongruous elephant-headed, pot-bellied god, Ganesha, radiating adbhuta rasa (strangeness), is loved like a relative. Hindus lavish equal adoration on the radiantly beautiful goddess, Lakshmi (wife of Vishnu) and the jet-black goddess Kali (Shiva’s consort) who is seen trampling over her prostrate husband. In India, God is not seen merely as a male force. Indian Gods and Goddesses are on equal footing when it comes to power-sharing; indeed, as in the case of Kali, sometimes the Goddess is more powerful.

All the gods are venerated because each one depicts a certain special aspect, or aspects, of the Universal. And since the Universal has myriad aspects, it is perhaps understandable that India has a galaxy of gods. This multiplicity of deities is the manifestation of the one ultimate reality, from which all flows and to which all must go. In Hinduism, to commune with any one of these is to be in touch with the divine.

- 112 min read

- 0

- 0