- Visitor:866

- Published on:

Legacy in Bengali Literature: Chandidas and Chaitanya Mahaprabhu

The popularity of Badu Chandidas lies as the writer of the legendary drama in verse, Shreekrishna Kirtana. Taking the Puranic tale of Krishnaleela with a notable influence of Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda and based on the simple village gossips about Radha-Krishna prevalent among the masses, the story revolves around three main characters- Krishna, Radha and Badai (Dyuti).

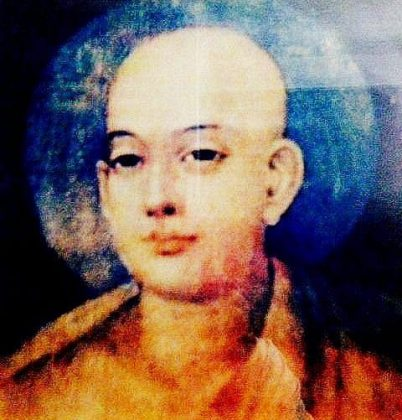

1. Chandidas: The first humanist poet of Bengal

Chandidas (1408 CE) was one of the most prominent and admired poets of Medieval Bengal. There are total four individuals found with the same name- Badu Chandidas, Dwija Chandidas, Din Chandidas and one only Chandidas without any byname. So, a dispute has been there in Bengali literature to ascertain whether all four were the same or different identities. The earliest among them is Badu Chandidas, whose identification is somehow recognized. He was born in either Nanoor or Chattna in Birbhum district of West Bengal. He came from an upper-caste Barendra Brahmin Family and was an ardent devotee of Goddess Basholi or Bishalakshmi. Possibly his birth name was Ananta and family surname was “Badu” and later given the title “Chandidas” by his Guru.

He was deeply in love with a lower caste girl Rami or Ramitara, a cloth-washer’s daughter, who inspired him to compose his first poem. This infinite, divine, unstained, pure and spiritual bond between them made Chandidas ostracized from society. It is heard that he was also not allowed to perform the death rites of his father due to his lower status.

The popularity of Badu Chandidas lies as the writer of the legendary drama in verse, Shreekrishna Kirtana. Basanta Ranjan Roy Bidwatballabh discovered a manuscript of this masterpiece of Bengali literature in 1916 and published that under Bangiya Sahitya Parishad. Deriving its inspiration from Shrimad Bhagavatam, the poetry recounts the eternal love story between Radha and Krishna.

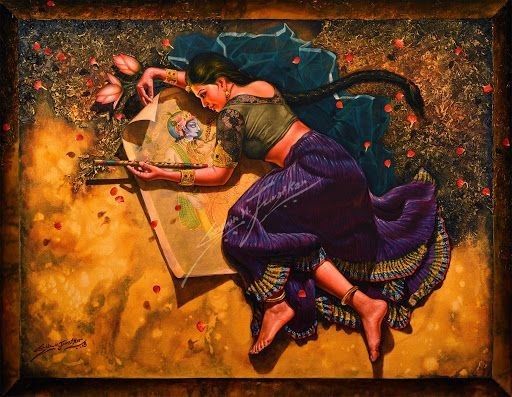

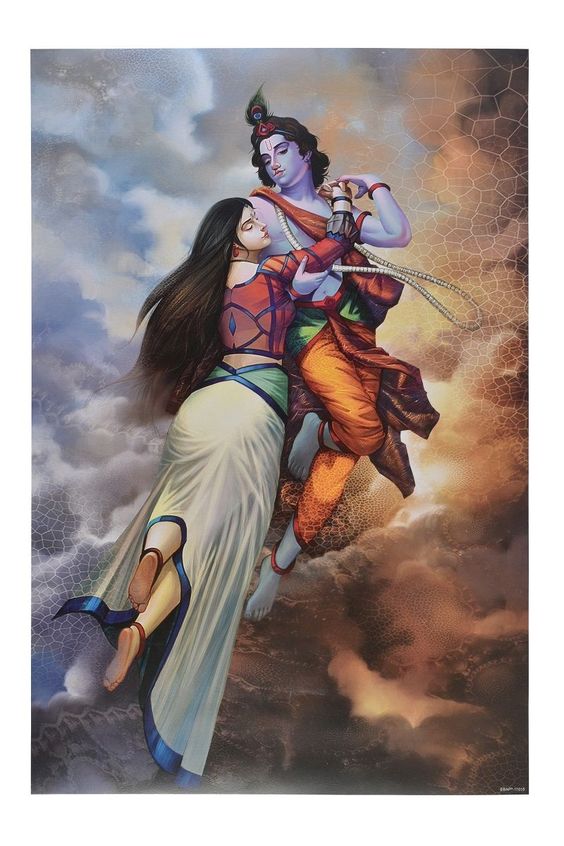

Taking the Puranic tale of Krishnaleela with a notable influence of Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda and based on the simple village gossips about Radha-Krishna prevalent among the masses, the story revolves around three main characters- Krishna, Radha and Badai (Dyuti). The verses are filled with conflicts and challenges in life, quarrels and anger and grudges. This makes the flow of the story moving on, engaging and dramatic. Also, mesmerizing songs are included here. The main theme revolves around Shringar Rasa and has influences from Jhumur songs, composed in Payar and Tripadi rhythum. Here, Radha’s longing for love is provided with a Bengali outlook and cultural mind-set and remains relevant today.

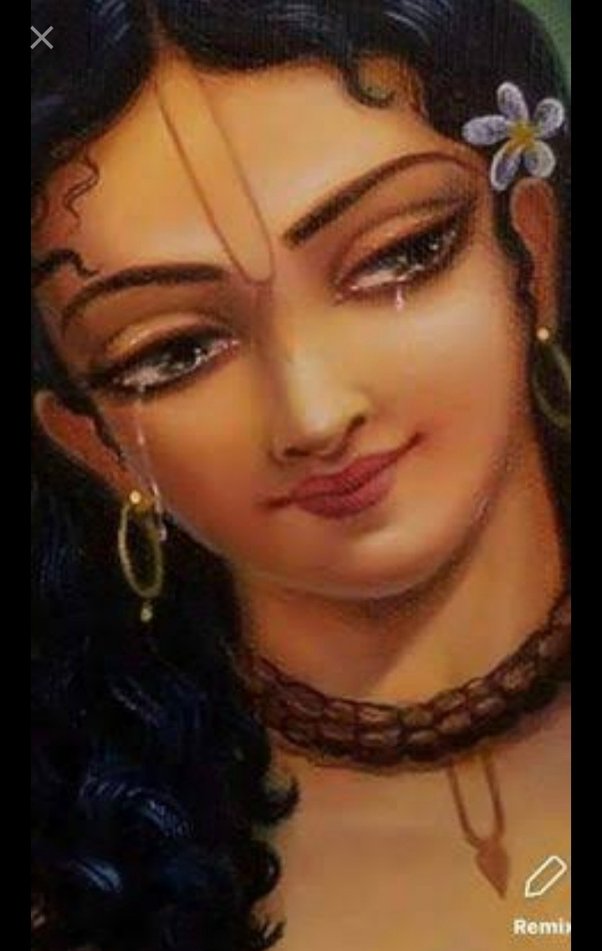

The poem is divided into thirteen parts. Chandidas constructed the character of Radha as a hermit and ascetic , having a self-sacrificing form with a tender image of love. Radha is a simple girl-next-door from the village whose gentle appearance is mixed with the complexities of daily life. The sudden emergence of love in Radha’s easy-going life and the story of her breakup with her lover make up its main emotional part. In this case, Chandidas has successfully amalgamated love with devotion with the skillful application of rhetoric is enough to bring out Bengali tears, emotions and feelings from their daily struggles.

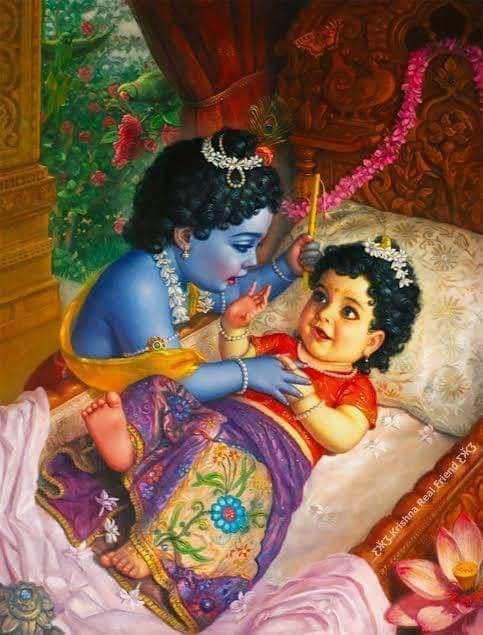

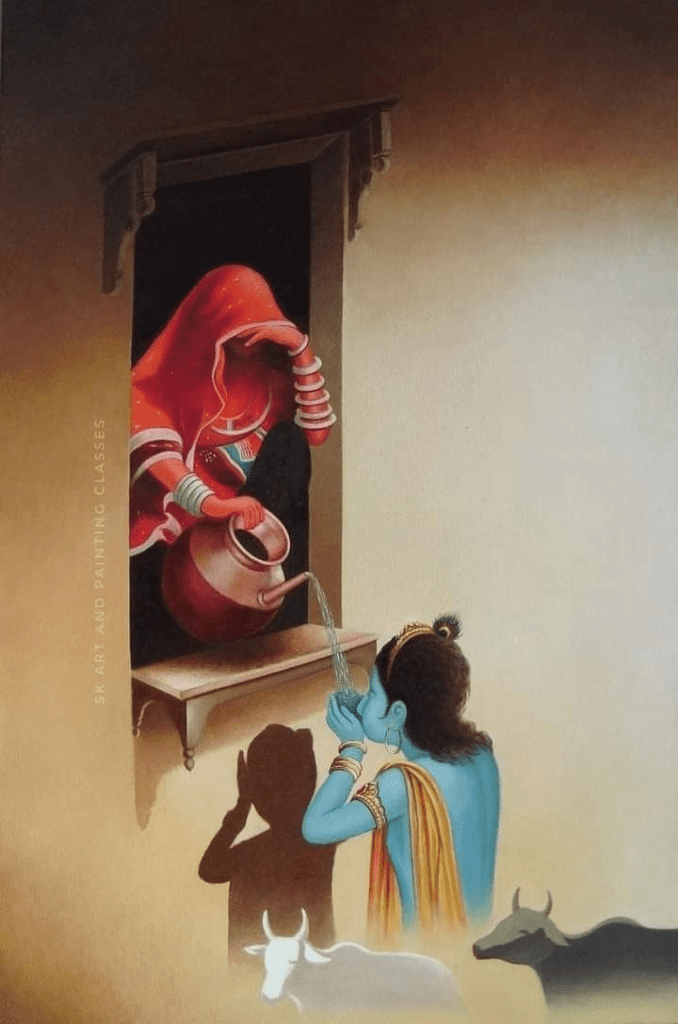

In the Janmakhanda of this poem, the birth of Radha and Krishna is described. In the Tambul Khanda, there is a description of the extraordinary beauty of Radha with the first love of Krishna is there, and from Dankhanda, the performance of Krishna as a giver and meeting with Radha and other tales like the story of the Gopis crossing the Yamuna with Radha Krishna’s boat and also time pass of Radha and Krishna on Yamuna river are also narrated. The Bharakhanda mentions Krishna carrying loads of milk and curds walking beside Radha as her bearer. Baru Chandidas recounts the incidence of Lord Krishna holding the umbrella on Radha’s head in Chatrakhand. Vrindavankhand mentions Lord Krishna’s forest pastimes and rasayatras with the gopis.

The Yamuna Khanda describes the disrobing of the gopis and the bathing for amusement in water Krishna. The Harkhand contains the story of Krishna’s theft of Radha’s necklace and Radha’s complaint against Krishna to Mother Yashoda. The verses further narrate the story of Krishna’s passion for Radha and taking revenge for Radha’s complaint by hitting with the Madan vana (arrow of love) The Vanshikhanda mentions Radha’s excitement on hearing Krishna’s flute and stealing of Krishna’s flute, followed by Krishna ardent appeal and ultimately returning of the flute. Finally, in the Radhaviraha section Krishna’s union with Radha, visiting Mathura and pain of detachment in Radha are presented. He has used prologues many times in his poem.

The verses holding the name of this first humanist poet of Bengal, have been many times knowingly or unknowingly recited at almost every home in Bengal from that time. Many dramas and movies are made about him. His famous saying “Sobar Upore manush sotyo, tahar opore nai” (Humanity is the ultimate truth above all, and nothing is beyond that) can be considered the finest epitome to understand the sense of humanity and philosophy of medieval Bengalis and Indians.

According to one legend, Chandidas was invited by the Muslim sultan of Gaur to perform music. There, the king’s queen or Begum fell in love with Chandidas after listening to his magical melody. This news made the sultan enraged and made him kill Chandidas by chaining him on the back of an elephant or crushing him under the feet of the elephant. The queen could not bear this torture for Chandidas and also gave up her life. Even Rami, enthralled by the passion of Begum’s love, bowed to her. However, many such stories are found about his life and still their truth is a matter of debate.

He was no doubt the greatest of all sympathetic and passionate musical poets of pre-Chaitanya era. Tasting the nectar of his verses even Chaitanya Mahaprabhu was enchanted as both of them were true lovers and fellow sufferers of Radha’s pain more than anyone else. Some verses of Chandidas are as follows.

“Soi keba sunaila shyama nama”- Friend, who has uttered the name of Shyama (Purba Raga)

“Jata Nibariye chai, nibar na jae re”- More I want to prohibit myself, the more I am unable to control (Prem Baichittya)

“Ki mohini jana badhu”- What a mesmerizing charm you know O new bride! (Akkhepanuraga)

“Badhu ki ar bolibo ami”- O bride, what more shall I say (Nivedana)

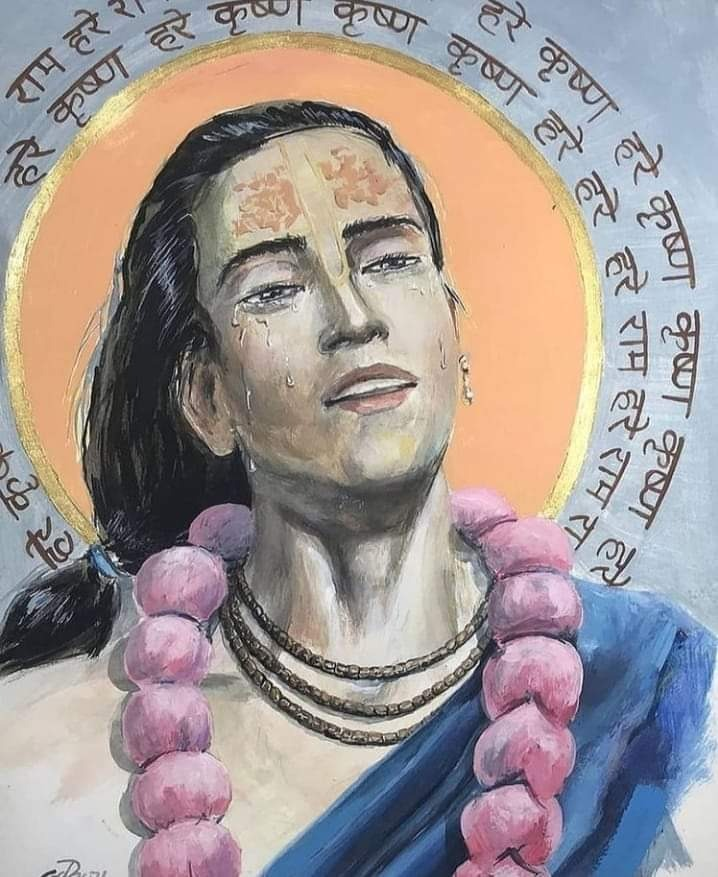

2. Impacts of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu on Bengali literature

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu has composed not a single verse in Bengali. So apparently his contribution to Bengali literature seems to be nil. Still his influence in Medieval Bengali literature remains very storng and undeniable. His groundbreaking arrival brought a great renaissance in the contemporary society and culture of Bengal. Mahaprabhu redirected the path of traditions in Bengali literature. Freedom of the defeated mind under the foreign Islamic rules and emotions of love and humanity underpinning the Hindu heart to move towards salvation created fresh values and directions of life following his footsteps.

In the following table, we will see both the direct and indirect influences of the saint in Bengali literature.

| Direct influences: | Vaishnav Padavali | The entry of spiritual relationship in the place of prior material love of Radha Krishna gave fresh and detailed interpretations of the entire Padavali literature. Moreover, new sections of Padavali, namely “Gaurchandrika” and “Gaur Padavali” were dedicated to the life of “Gaurchandra” or Chaitanya. |

| Biography of Chaitanya | The “Chaitanya Bhagavat” by Vrindaban Das ostarted a new trend of biopic considering the Godly character of Mahaprabhu. Here, later examples of Chaintanyamangal by Jayananda, Chaitanya Mangal by Lochan Das and Chaitanya Charitamirta of Krishnadas Kaviraj revealed new paths towards the change. | |

| Mangal Kavya | The narrow-mindedness, brutality, cruelty and selfishness of various Gods and Goddesses of Mangal Kavya in Pre-Chintainya era diminished a lot and transformed into more Godly, pleasant and divine glory. For example, the development of natures of of vengeful Chandi into Mother Avaya (one who assure protection) in the hands of Mukunda Chakravarty and Dwija Madhav and kind image of Dharam Thakur in Dharma Mangal Kavya, can be considered. | |

| Indirect effects: | Translations | The social, cultural ambience and characters from Ramayana, Mahabharata and Bhagavata in the Bengali language under the influence of Vaishnavism are the instances worth mentioning here. |

| Shakta Padavali | Some argue that the versus that signified the love for children or Vatsalya Rasa and Uma Sangit (Songs of Mother Uma) like Agamani and Vijaya songs faced changes due to Chaitanya’s cordial and polite approach. | |

| Folklores | Here, the effect of Chaitanya is strong. The instances of Mymensingh Geetika, the collection of folk ballads from Mymensingh, Bangladesh and most notably the Baul school of thought and music, searching for the “Moner Manush” (the correct person to love in mind) are finest epitomes. |

Gour Chader dorbare

Ekmon jar sei jete pare

Abar dui mon hole porbi faade

Parbi na pare jete (Song of Bhaba Pagla)

In the assembly of my Nitai Chand

At the court of my Gour Chand

Only the one with one mind can visit

If you are in doubt or two-minded, you are in the trap

You will not reach the shore!

Thus, the prevalent harshness in spiritual themes found in many Bengali compositions gradually transformed into more soft and submissive like when they say “Debotare priyo kori, priyore kori Debota” (Making God the beloved one and the lover my God), deriving the influences from Mahaprabhu’s style of devotion. However, whether this change was good or bad for the Hindus, that is another matter of debate!

Hare Krishna!!

References:

https://www.freepressjournal.in/mind-matters/chandidas-the-great-vaishnava-poet

Devnath, Samaresh (2012). “Chandidas”. In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

Bhowmik, Dulal (2012). “Srikrishnakirtan”. In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

Stewart, T. K. (1986). “Book Review: Singing the Glory of Lord Krishna: The “Śrīkṛṣṇakīrtana””. Asian Folklore Studies. Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture. 45 (1): 152–154. doi:10.2307/1177851. JSTOR 1177851.

https://www.targetsscbangla.com/ chandidas

https://sobbanglay.com/sob/badu-chandidas /

চৈতন্য মহাপ্রভু ও মধ্যযুগীয় বাংলা সাহিত্য

Originally published at: bengalrenaissance.org

Center for Indic Studies is now on Telegram. For regular updates on Indic Varta, Indic Talks and Indic Courses at CIS, please subscribe to our telegram channel !

- 433 min read

- 0

- 0