- Visitor:21

- Published on:

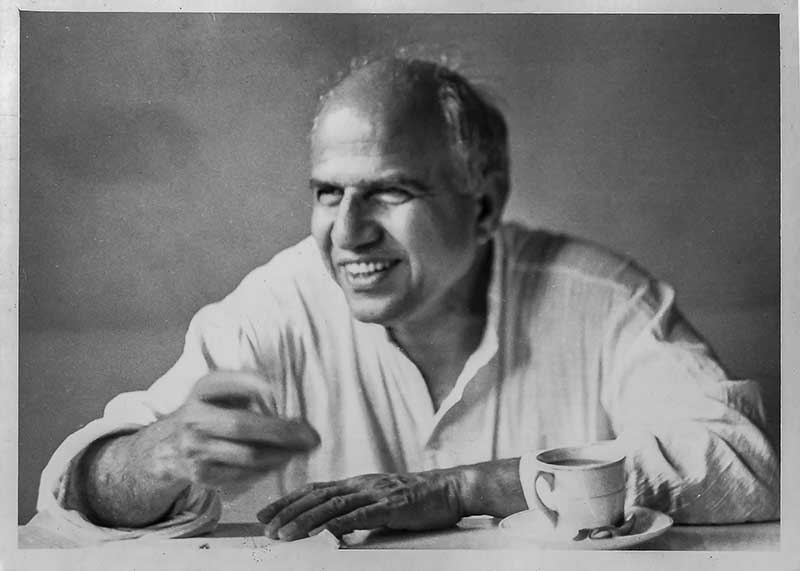

Sensuality and Spirituality

This is an excerpt from Balraj Khanna’s book “Human and Divine”. Depiction of sensuous pleasure has never been suppressed in Hinduism, because the human body is not seen as separate from the spirit. Even with Jainism, whose followers adhere to the world’s strictest regime of vegetarianism, bordering on extremism, we see its godly Tirthankara’s (divine preceptors) as well-proportioned, robust beings despite their austere diet, although stern, they have a sense of well-bring and exude a spiritual calm.

One aspect of Indian sculpture that Westerners find somewhat baffling is perhaps its unabashed celebrating of sensuality. Christianity’s ultimate image is Christ on the cross. There is no such defining image in Hinduism, although Buddhism highlights detachment, and Jainism exalts the ascetic. Islam of course does not permit ‘human’ portrayal whether of the divine or profane.

Depiction of sensuous pleasure has never been suppressed in Hinduism, because the human body is not seen as separate from the spirit. Even with Jainism, whose followers adhere to the world’s strictest regime of vegetarianism, bordering on extremism, we see its godly Tirthankara’s (divine preceptors) as well-proportioned, robust beings despite their austere diet, although stern, they have a sense of well-bring and exude a spiritual calm.

Even the Buddha displays a certain air of sensuality. He is usually seen with a slightly round belly, from the earliest of his representations (first to second century AD) from Mathura, 120 miles south of New Delhi. The flamboyant Bodhisattvas – the Buddha’s to come, or those Buddhist sages who postponed attainment of their own nirvana in order to help others achieve theirs – from Gandhara (first to fifth century AD), a region spread over present-day northwest Pakistan and Afghanistan, are magnificently attired and sometimes moustached.

They seem more like Princes than Buddhist monks who earned their living by begging. Sculpted under Hellenistic influences (Gandhara was in close contact with Greece both culturally and aesthetically), these Bodhisattvas represent the essentially princely Buddha whose opulence was only abjured by the ‘historical’ Buddha, Siddhartha.

Hindu sculpture often radiates an extraordinary degree of sensuality, and India is dotted with temples amply demonstrating the fact that sensuality has always been at the heart of Indian creativity, itself a result of profound religious preoccupations. The reasons for this tantalizing contradiction are as compelling as they are simple. Indians consider creation to be the consequence of male and female principles of nature coming together. They believe that the union of man and woman is not only obviously natural, but also something to be celebrated. It prefigures a transcendental, supreme bliss – the union of the human soul with the Great Soul, Jivatma with Paramatma. Hindu art has traditionally celebrated the expression of sensuality as being fundamental to finding wholesomeness in life.

Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra (fourth century AD), the world’s first and most celebrated book on the art of love-making, is not a mere sex manual. Rather, it is a poetic treatise in which, according to Hindu principles, the joys of the erotic are extolled as essential to a balanced life. The twelfth century Bengali poet, Jayadeva, wrote some of the most moving love songs in world literature, which were devoted entirely to the love life of Krishna, the Divine Lover. And the tenth to eleventh century temples of Khajuraho in Madhya Pradesh and Konarak in Orissa, are festooned with explicit erotic imagery which, particularly at Khajuraho, is astoundingly beautiful.

It charms, it seduces, it makes one wonder at the sheer audacity of its creation and their powers of conceptions and execution – bold but sensitive, fantastic yet poetic. It would be a grave error to regard these sculptures as anything but great works of art. They represent the beauty and the abundance of life in which the act of procreation is afforded a transcendental role.

Elsewhere in India, Mithuna (couples engaged in amorous embraces) adorn the walls of temples and other religious buildings. They represent, often in high relief at the entrance of a temple, a warm welcome. So lovingly engrossed in each other and so effective through their fullness of form and rhythm, the presence of Mithuna at a holy shrine bridges the gap between the human and the divine. It makes God less severe, bringing him closer to man.

- 10 min read

- 0

- 0