- Visitor:18

- Published on:

The Symbolism of Shri Ganpati

It must be evidently clear to all sensitive thinkers that the representations given in the various symbolisms are not as many different Deities, but they are vivid pen-portraits of the subjective Truth described in the Upanishadic lore. The student must have the subtle sensitivity of a poet, the ruthless intellect of a scientist, and the soft heart of the beloved, in order to enter into the enchanted realm of mysticism created by the poet-seer, Vyasa. To the crude intellect and its gross understanding, these may look ridiculous; but art can be fully appreciated only by hearts that have art in them. When we review the Puranas with at least a cursory knowledge of Vedanta, they cannot but strike us as extremely resonant with the clamouring echoes of the Upanishadic melody.

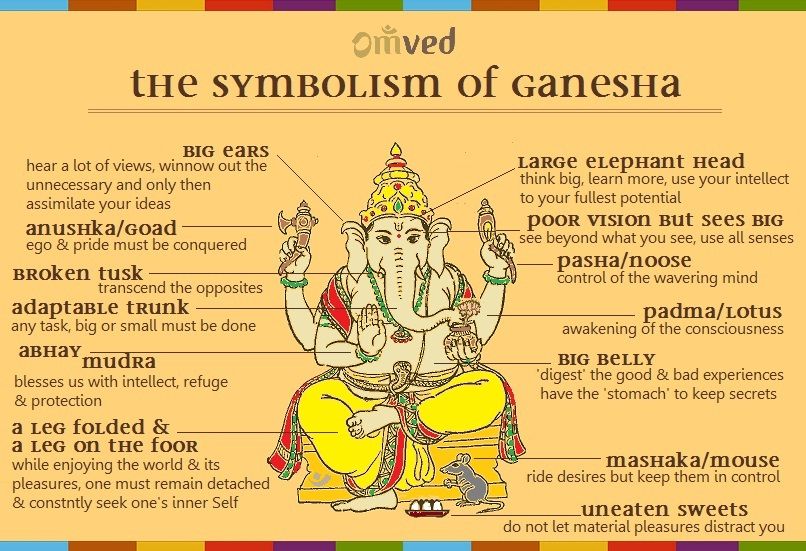

Lord Shiva’s first son is described as the Supreme Leader (Vinayaka) or as the Leader of the “Ganas” (Ganapati), who attends upon and follows at all times Lord Shiva, or as the Lord of all Obstacles (Vighneswara). These names clearly show that He is a Master of all Circumstances and not even the divine forces can ever obstruct His path. Since He is thus the Lord of all obstacles, no Hindu ritual or auspicious act is ever undertaken without invoking Him. With His grace, it is believed that no undertaking can fail due to subjective or objective obstacles.

Ganapati is said to have two spouses, Buddhi (Intellect) and Siddhi (Achievement). Thus He is the Master of Knowledge and Achievement.

In this characterisation Shri Ganapati represents a possessor of Perfect Wisdom, and a Fully Realised Vedantin. Westerners are shocked to notice that Hindus revere a divine form which is so ridiculous and absurd. But the Elephant-Headed Lord of all difficulties in life indeed represents the highest and the best that have ever been given in our Scriptures.

To a Vedantic student, since his “path of knowledge” is essentially intellectual, he must have a great head to conceive and understand the logic of the Vedantic thought and, in fact, the truth of Vedanta can be comprehended only through listening to a teacher and, therefore, Sravana (listening) is the initial stage to be mastered by the new initiate. Therefore, Sri Ganapati has large ears representing continuous and intelligent listening to the teacher.

After “listening” (Sravana) to the truths of the Upanishads, the Vedantic student must independently “reflect” (manana) upon what he has heard, for which he needs a sensitive intelligence with ample sympathy to discover in himself sufficient accommodation for all living creatures in the universe.

His intellect must have such depth and width in order to embrace in his vision the entire world-of-plurality. Not only must he, in his visualization, embrace the whole cosmos, but he must have the subtle discriminative power (Viveka) in him to distinguish the changing, perishable, matter-vesture from the Eternal, Immutable, All-Pervading Consciousness, the Spirit. This discrimination is possible only when the intellect of the student has consciously cultivated this power to a large degree of perfection.

The trunk, coming down the forehead of the elephant face, has got a peculiar efficiency and beats all achievements of man and his ingenuity in the mechanical and scientific world. Here is a “tool” which can at once uproot a tree or pick up a pin from the ground. The elephant can lift and pull heavy weights with his trunk and, at the same time, it is so sensitive at its tip that the same instrument can be employed by the elephant to pluck a blade of grass.

The mechanical instruments cannot have this range of adaptability. The spanner that is used for tightening the bolts of a gigantic wheel cannot be used to repair a lady’s watch. Like the elephant’s truck, the discriminative faculty of an evolved intellect should be perfect so that it can use its discrimination fully in the outer world for resolving gross problems, and at the same time, efficiently employ its discrimination in the subtle realms of the inner personality layers.

The discriminative power in us can function only where there are two factors to discriminate between. These two factors are represented by the tusks of the elephant as the trunk is between them. Between good and evil, right and wrong, and all other dualities must we discriminate and come to our own judgements and conclusions in life. Sri Vinayaka is represented as having lost one of His tusks in a quarrel with Parasurama, a great disciple of Lord Shiva. This broken tusk indicates that a real Vedantic student of subjective experience is one who has gone beyond the pairs of opposites (dwandwaatita).

He has the widest mouth and the largest appetite. In Kubera’s palace, he cured Kubera’s vanity that in his riches he had become the ‘Treasurer of the Heavens’. When Kubera offered Him a dinner He ate up all the food prepared for the dinner. Thereafter, He started eating the utensils and then the decorative pandal, and still He was not satisfied. Then His father, Lord Shiva, approached Him and gave Him a handful of “puffed rice”. Eating this up he became satisfied.

The above story narrated in the Puranas, is very significant that a Man of Perfection has an endless appetite for life – he lives in the Consciousness and to him every experience, good or bad, is only a play of the infinite through him. Lord Shiva, the Teacher, alone can satisfy the hungers of such sincere students by giving them a handful of “roasted rice”, representing the “baked vasanas”, burnt in the Fire of Knowledge. When one’s vasanas are burnt up, the inordinate enthusiasm of experiencing life is also whetted. A Man of perfection must have a big belly to stomach peacefully, as it were, all the experience of life, auspicious and inauspicious.

When such a mastermind sits dangling his foot down, it is again significant, in the symbolism of the Puranas. Generally we move about in the world through the corridors of our experiences on our two feet, or the inner subtle body, the mind and the intellect. A Perfect Man of Wisdom has integrated them both to such an extent that they have become One in him – an intellect into which the mind has folded and has become completely subservient.

At such a great Yogi’s feet are the endless eatables of life-meaning, the enjoyable glories of physical existence. All powers come to serve him, the entire world of cosmic forces are, thereafter, his obedient servants, seeking their shelter at His feet; the whole world and its environment is waiting at His feet for His pleasure and command.

In the representation of Sri Vinayaka we always find a mouse sitting in the midst of the beautiful, fragrant ready-made food, but if you observe closely, you will find that the poor mouse is sitting looking up at the Lord, shivering with anticipation, but not daring to touch anything without His command. And now and then He allows the mouse to eat.

A mouse is a small little animal with tiny teeth, and yet, in a barn of grain a solitary mouse can bring disastrous losses by continuously gnawing and nibbling at the grain.

Similarly, there is a “mouse” within each personality, which can eat away even a mountain of merit in it, and this mouse is the power of desire. The Man of Perfection is one who has so perfectly mastered this urge to acquire, possess and enjoy this self-annihilating power of desire, that it is completely held in obedience to the will of the Master. And yet, when the Master wants to play His part in blessing the world, He rides upon the mouse – meaning it is a desire to do service to the world that becomes His vehicle to move about and act.

The Puranas tell us how once Sri Vighneswara, while riding His mouse, was thrown down and it looked so ridiculous that the Moon laughed at the cosmic sight. It is said in the Puranas that the great bellied Lord Vinayaka looked at the Moon and cursed that nobody would ever look at it on that day – the Vinayaka Chathurthi.

When a Man of Perfection (Vinayaka) moves about in the world, riding on His insignificant looking vehicle, the “desire” to serve (mouse), the gross intellect of the world (Moon – the Presiding Deity of the Intellect) would be tempted to laugh at such Prophets and seers.

The Lord of Obstacles, Sri Vighneswara, has four arms representing the four-inner-equipments (antahkarana). In one hand he has a rope, in another an axe. With the axe, he cuts off the attachments of His devotees to the world of plurality and thus ends all the consequent sorrows, and with the rope, pulls them nearer and nearer to the Truth, and ultimately ties them down to the Highest Goal. In his third hand He holds a rice ball (modaka) representing the reward of the joys of sadhana which He gives His devotees. With the other hand He blesses all His devotees and protects them from all obstacles in their Spiritual Path of seeking the Supreme.

On the Spiritual pilgrimage, all the obstacles are created by the very subjective and objective worlds in the seeker himself; his attachment to the world of objects, emotions and thoughts, are alone his obstacles, Sri Vighneswara chops them off with the Axe and holds the attention of the seeker constantly towards the higher goal with the rope that he has in His left hand. En route he feeds the seeker with the modaka (the joy of satisfaction experienced by the evolving seeker of Reality) and blesses him continuously with greater and greater progress, until at last the Man of Perfection becomes Himself the Lord of obstacles, Sri Vighneswara.

The above three or four examples should clearly bring to your mind the art employed by Vysaya in his mystical word paintings. It must be evidently clear to all sensitive thinkers that the representations given in the various symbolisms are not as many different Deities, but they are vivid pen-portraits of the subjective Truth described in the Upanishadic lore.

The student must have the subtle sensitivity of a poet, the ruthless intellect of a scientist, and the soft heart of the beloved, in order to enter into the enchanted realm of mysticism created by the poet-seer, Vyasa. To the crude intellect and its gross understanding, these may look ridiculous; but art can be fully appreciated only by hearts that have art in them. When we review the Puranas with at least a cursory knowledge of Vedanta, they cannot but strike us as extremely resonant with the clamouring echoes of the Upanishadic melody.

Source : Symbolism in Hinduism – Swami Chinmaynanada, Central Chinmaya Mission Trust

- 9 min read

- 0

- 0