- Visitor:24

- Published on:

Beyond Saussure and Derrida: Bhartrhari’s Holistic view of Language

It is obvious to any reader of Derrida how this ‘condemnation’, in a paradoxical manner, provides ammunition for Derrida’s deconstruction of the texts of Saussure and Rousseau. As far as I know, such condemnation of writing was conspicuous by its absence in the Indian tradition in which Bhartṛhari flourished. Hence the sphoṭa theory of language was not ‘logocentric’ in any damning sense. As I have said, both sonic and graphic symbols can be the ‘illuminator’ of the sphoṭa, and being the illuminator, either of them can be identified with the illuminated. Both speech and writing can be in perfect harmony (where talk of ‘violence’ would be pointless) in Bhartṛhari’s holistic view of language.

It would be relevant today to talk about the apparent opposition between the speech and the writing, the audible parts and the visible inscriptions that are supposed to represent languages. Modern Western linguists (notably Saussure and others) have been eloquent about the primacy of speech or spoken words (as opposed to writing) as the indispensable foundation of linguistics. Saussure condemned his nineteenth century predecessors, the grammarians, for their ‘scriptism’ which presumably conflated writing with language, letters with sounds. This has been called by Saussure ‘the tyranny of writing’, even a ‘monstrosity’ or distortion.

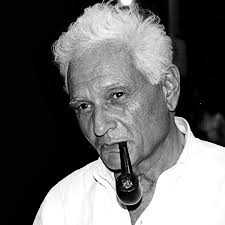

In spite of this dire warning, some recent linguists (Harris, 1980, 8; Lyons, 1968, 9), have shown that this scriptist bias has persisted in many corners of the field of linguistics, for the temptation to analyze speech into writing (Lyons has called it the ‘orthological dogma’) is one to which many modern linguists have inadvertently succumbed. Anybody familiar with J. Derrida’s writing, for example, knows the opposite view, which regards logocentrism (particularly the centrality of speech or the sonic element in language) as a bias which has suppressed free thinking about language and retarded our reflection on the origin and status of writing and its proper place in our study of language.

The purpose of this critique of the so-called Western metaphysics, the ‘deconstruction’ of the texts of Saussure, Rousseau, etc., to expose the dangers and destructive effects of logo centrism, has been to develop a science of writing called grammatology. But this is not to say that writing is better than speech. Rather, the attempt, as I understand it, is to show that the said opposition is an illusion, since language, or the origin and development of language, has historically been as much involved with structured speech as with structured writing, ‘for it is indeed history that one must stop in order to protect language from writing’ (Derrida, 1976, 42).

From the point of view of Bhartṛhari’s sphoṭa or the notion that language is an integral part of our consciousness, we may say that both speech and writing can alike be the ‘illuminator’ of the sphoṭa. One is not primary and the other does not particularly distort the sphoṭa. In fact, both can equally ‘distort’ the sphoṭa in a non-pejorative sense. Both ‘transform’ (cf. vikāra) the untransformable, unmodifiable sphoṭa, which is part and parcel of everybody’s consciousness. In the light of Bhartṛhari’s theory, therefore, both the translations and the original (whether vocal or written) are in some sense transformations.

In spite of Bhartṛhari’s explicit use of śabda and speech, I would argue that he was not guilty of ‘logocentrism’ in Derrida’s sense. In fact, in Indian tradition, where oral transmission of the Vedas (wrongly called the Scriptures, for the Sanskrit term is Śruti = something to be heard) was the norm, where oral recitation of the Buddha’s dialogues (the Buddhist scriptures where each section always starts ‘Thus, I have heard…) lasted for centuries after the death of the Buddha (and the same is true of Jainism), and where oral transmission of other texts called śāstras continued for a long time and texts were first memorized by students before any explanation or understanding was attempted, it is no wonder that the word for language was the word for sound (śabda).

All these facts of the Indian tradition might have been historically conditioned because scholars faced extreme difficulties due to climatic and other conditions, for example the monsoons, in preparing and preserving writing materials. But the tradition, I argue, is free from the fault of logocentrism. For logocentrism, as I see it, flourishes and derives nourishment from the explicit condemnation (and also ‘damnation’ – it has been called a sin) of writing, otherwise ‘speech’ cannot be promoted to the prime place.

And for this point one can turn to Derrida. It is obvious to any reader of Derrida how this ‘condemnation’, in a paradoxical manner, provides ammunition for Derrida’s deconstruction of the texts of Saussure and Rousseau. As far as I know, such condemnation of writing was conspicuous by its absence in the Indian tradition in which Bhartṛhari flourished. Hence the sphoṭa theory of language was not ‘logocentric’ in any damning sense. As I have said, both sonic and graphic symbols can be the ‘illuminator’ of the sphoṭa, and being the illuminator, either of them can be identified with the illuminated. Both speech and writing can be in perfect harmony (where talk of ‘violence’ would be pointless) in Bhartṛhari’s holistic view of language.

Source : The Word and the World : India’s Contribution to the Study of Language – B K Matilal, OUP

- 12 min read

- 0

- 0