- Visitor:19

- Published on:

Will Corona Virus cure our Colonial Hangover?

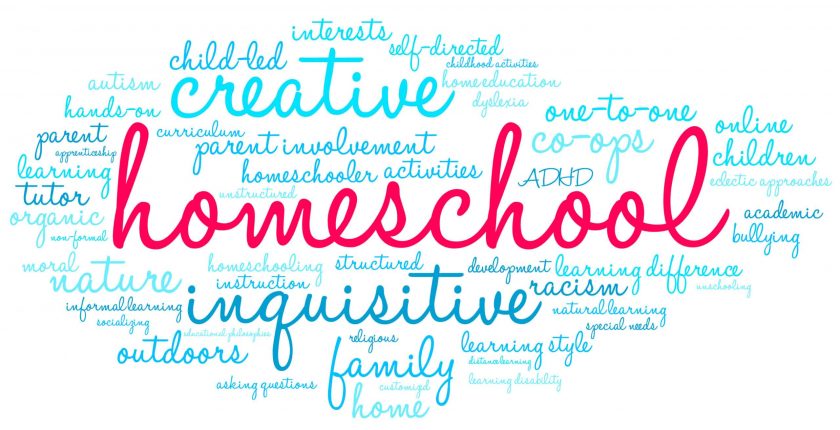

As the novel Corona Virus threatens to disrupt our lives, most of us are wary and pessimistic about what the future holds. But our traditional wisdom tells us that a moment of crisis is also a moment of transformation. This may be especially true in the domain of education that has witnessed a huge impact by the novel Corona Virus. Schools and colleges remain closed in almost all countries of the world and some fear that educational institutions will remain closed for a long time even after the lockdown is lifted. What are the solutions? Read on to know more.

Introduction

As the novel Corona Virus threatens to disrupt our lives, most of us are wary and pessimistic about what the future holds. But our traditional wisdom tells us that a moment of crisis is also a moment of transformation. This may be especially true in the domain of education that has witnessed a huge impact by the novel Corona Virus. Schools and colleges remain closed in almost all countries of the world and some fear that educational institutions will remain closed for a long time even after the lockdown is lifted.

This has forced educational establishments across the country (India) to reinvent their teaching methods and many institutions have now adopted the online mode of education. Now, the bigger question that this article aims to explore is whether the trend of online education is merely a passing remedy for a temporary problem or is it a long overdue curative measure for our education system that is rooted in our colonial past.

Colonial Education: A Historical Background

In February 1835, Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859) delivered his famous minute in which he dismissed the entire Oriental literature as being not worthier than “a single shelf of a good European library”. Shortly thereafter, the then Governor-General, Lord William Bentinck (r.1828-1835) passed a resolution which came to be known as the English Education Act. Bentinck’s resolution, which was soon enacted into legislation by the Council of India, significantly changed the nature of colonial discourse. Indian literary texts, languages and culture were no longer found to have any moral or intellectual value.

At the same time, the bureaucratisation of education was begun in earnest. An Education Department was established in 1854 along the directions of the colonial authorities in London who believed that it was “advisable to place the superintendence and direction of education upon a more systematic footing.” [2] The functions of this Education department, as the first Indian Education Commission (1882) broadly classified under three heads: ‘Instruction’, ‘Inspection’ and ‘Control’. In other words, the colonial government instituted a uniform curriculum, compulsory attendance of students, and centralised control of educational institutions in India. Let us see how each of these three colonial hangovers can be cured by the Corona Virus.

Hangover #1: Uniform Curriculum

The colonial state had sought to streamline the dissemination of knowledge by recommending a uniform set of textbooks to be used across all government schools. Indigenous schools, as colonial surveyors had discovered, lacked both written textbooks and good infrastructure. The colonial state also sought to ‘improve’ the old patshala teachers by introducing reformatory measures so that the guru who was hitherto regarded as the central figure of the patshala, was no longer to exercise ‘unquestioned authority’.[3] In his well-known study of the Bengali patshalas, K. Shahidullah has discussed how government regulations “dictated what was to be taught in the patshalas, how it was to be taught, how discipline was to be maintained, and how, in general, the patshala was to be made more efficient.” [4]

Now, in the era of online education, the teacher has a lot of autonomy to decide the course of instruction. In fact, teachers need not adhere to a single ‘correct’ textbook since there are multiple sources that inform and enrich our understanding of a given subject. As a result, both teachers and students are free to consult and share resource materials that may enhance their understanding. Once uploaded on the cloud server, these resource materials can be easily distributed among students who can access them from any place at anytime. This brings us to the second hangover of colonial education: the matter of attendance.

Hangover#2: Compulsory Attendance

In the nineteenth century, it was necessary to train the youth in such a manner that they would become efficient workers in the factories where they would be employed. The industrial workers were trained to be punctual and disciplined because all workers had to assemble at one place at a given time for the assembly line to function properly. So, the education model of the time served this need and it was made mandatory for students to compulsorily attend a classroom session. According to Alvin Toffler, the “covert curriculum” of industrial era education consisted of three courses: “one in punctuality, one in obedience, and one in rote repetitive work” [5] This form of schooling was also necessary because the relevant information and training was available at a given place and a given time. As a result, there was heavy investment on building good infrastructure for classrooms and hostels to accommodate students who travelled from distant places.

The era of online education has completely obviated the necessity to be physically present at a specific location. Any person with internet access can join the online classroom from any geographical location. Moreover, the need to join a live classroom session is not necessary because the video recording of the lecture can be easily uploaded on the cloud server which students can access at any convenient time of their choice. Therefore, the colonial era policies do not apply in the online era where the flow and distribution of information does not depend upon place and time. This radical change in information flow is a cure for the old hangover of compulsory attendance. Eliminating this rule can give students enough space and freedom to think and learn. If needed, schools can track attendance by the number of views and IP address of the viewers.

Hangover #3: State Control

In 1831, when the G.C.P.I. issued their first report, the total number of educational institutions under State control was 14 with 3,490 pupils. [5] Gradually, the State increasingly sought to expand its control by bringing more educational institutions under its umbrella and it became directly involved in running the schools. Not only did the colonial government discontinue the earlier tax exemptions to village communities, but it also devised a new system of ‘Grants-in-aid’ that would determine how the State was to disburse funds to select schools. It was now only the State that could recognise a school and endow grants provided the school fulfilled certain conditions. The Wood’s despatch ruled that aid would be given to all schools that gave ‘a good secular education’. The other pre-requisites were that these schools should be under adequate local management and that “their managers consent that the schools shall be subject to Government inspection, and agree to any conditions which may be laid down for the regulation of such grants.”[6]

Today, in the twenty-first century when popularity and recognition are judged by the number of “views” for a video on the internet, it is anachronistic for an educational institution to be ‘recognised’ by the government. The era of online education will ensure that ‘good’ instruction will automatically receive more public views even if such instruction is not secular. Also, many successful online academies such as the Khan Academy have shown they can be profitable without depending on the government to fund them.

Hangover #4: Examinations

Besides imposing a uniform curriculum comprising of standard textbooks, the colonial state had instituted an examination system to test the students’ knowledge of the curriculum and certify their eligibility for promotion to the next grade. Examinations were a way to ensure strict adherence to the code of instruction laid down by the state. “The official function of the examination system,” as Krishna Kumar has noted, “was to evolve uniform standards of promotion, scholarship and employment.” [7] Thus, the colonial government controlled and monitored every lesson that was taught in public institutions, from the elementary to the collegiate level.

In today’s information age, when assessment is done easily by way of online tests, there is no need for examination and supervision. More importantly, students can learn highly specialised courses and receive certifications after they pass the online assessment. Leading companies like Google and Microsoft are now offering their own courses and certifications for skills that are highly relevant for future job roles. So, there may be no need for parental pressure since aspirants can opt what they wish to learn and education can be more closely connected to professional life. In the coming years, we will also see a growing culture of “home office” and online education may be just the right way to prepare for that culture.

Conclusion

This article argues that the current global pandemic may be viewed as a boon for education by showing us a fresh alternative to the existing model of education that we have inherited from our colonial past. The novel Corona Virus has given us a golden opportunity to rid ourselves of old colonial hangovers that are not only Eurocentric but also anachronistic.

Notes and References

- See “Minute recorded in the General Department by Thomas Babington Macaulay, law member of the governor-general’s council, dated 2 February 1835.” in Lynn Zastoupil and Martin Moir, The Great Indian Education Debate, 161-174.

- Paragraph 17 of “Despatch No. 49. Dated the 19th July 1854”, Richey, Selections from Educational Records (Part II), 369.

- Kazi Shahidullah, “The Purpose and Impact of Government Policy on Patshala Gurumashoys in Nineteenth Century Bengal.” In Nigel Crook, Ed. The Transmission of Knowledge in South Asia (Oxford University Press, 1996), p.127.

- Shahidullah, ibid., p.128.

- See “The Covert Curriculum” in Alvin Toffler, The Third Wave, 45.

- Report of the General Committee of Public Instruction. Quoted in Howell, Education in British India, prior to 1854 and in 1870-71, 23.

- Paragraph 53 of “Despatch No. 49. Dated the 19th July 1854” in Richey, Selections from Educational Records (Part II), 379.

- Krishna Kumar, Politics of Education in Colonial India, p.59.

- 9 min read

- 0

- 0