- Visitor:39

- Published on: 2025-09-23 03:05 pm

Significance of Equinox and Solstice for the Four Navratris: A Scientific and Spiritual Study

In the Hindu calendar there are four Navratris theoretically observed over the course of a year. Two of these are more prominently celebrated (Mahashakti or full Navratri), while two are more subdued or esoteric (Gupt or secret Navratri). These four occur at four key junctions in the year that correspond to major astronomical events — the equinoxes and solstices. A close look at how these celestial phenomena align with the Navratris reveals a rich interweaving of natural, physiological, psychological, and spiritual rhythms, which underlie much of the traditional significance attributed to Navratri. This essay explores this connection in depth, from the mechanics of the equinox and solstice to their effects on human life, and how the pattern of the four Navratris harnesses these effects for renewal, purification, and rebalancing.

.jpg)

Astronomical Foundations: What are Equinoxes and Solstices

An equinox occurs twice each year, around March 20‑21 (the vernal or spring equinox in the Northern Hemisphere) and around September 22‑23 (the autumnal equinox). At an equinox the Sun is positioned directly above the Earth’s equator; day and night are approximately equal in duration globally. The word “equinox” comes from Latin aequus (“equal”) and nox (“night”) though in practice day length may vary slightly due to atmospheric refraction and definitions of sunrise/sunset.

Solstices likewise occur twice a year: around June 21 (the summer solstice in the Northern Hemisphere, when the Sun reaches its farthest point north relative to the equator) and around December 21 (the winter solstice, when the Sun is farthest south). These mark the longest and shortest days of the year respectively. The solstices and equinoxes together mark the four cardinal points of the Sun's apparent path across the sky, and thus are the main anchors of the solar year.

These astronomical events bring with them shifts in solar energy, length of daylight, temperature, humidity, seasonal weather patterns, and consequential effects on ecosystems, agriculture, and human physiology. Traditional calendars in many cultures, including in India, tie religious festivals to these shifts. In Hindu tradition, many rituals and festivals occur at or near these equinoctials or solstitial transitions, to mark seasonal changes, in recognition of their influence not only on the outer world but on inner life.

The Four Navratris: Full (Mahashakti) and Gupt (Secret)

According to Hindu texts and practices, the four Navratris are:

Vasant or Chaitra Navratri in spring (around March‐April), often called Vasant Navratri.

Sharad or Ashvin Navratri in autumn (around September‑October), often the most widely celebrated, also called Sharadiya or Maha Navratri.

Gupt (Secret) Navratri in Ashadha (June‑July).

Gupt Navratri in Magha (January‑February).

The word “Gupt” implies that these two are less visible in public practice, more inward, less widely observed in many regions, though they are recognized in scriptural sources. The two Mahashakti Navratri are heavily ritualized, including fasting, public worship, dance and cultural festivities; the Gupt Navratris are more esoteric, used by seekers of deeper spiritual power, often observances of austerity and introspection.

Alignment of Navratris with Equinoxes and Solstices

Each of the four Navratris corresponds approximately to one of the four astronomical transition points (two equinoxes, two solstices).

Chaitra Navratri / Vasant Navratri aligns with the Vernal (Spring) Equinox. This is the time when Earth emerges from winter, daylight increases, temperatures begin to rise, and new growth begins in flora. The equinox marks a balance between day and night, light and dark. The tradition of beginning Navratri at this time can be seen as aligning a spiritual renewal to this natural renewal.

Sharadiya Navratri / Ashvin Navratri corresponds roughly with the Autumnal Equinox. After the monsoon, as rains recede and humidity drops, as the Sun’s declination moves south, the seasons shift toward cooler weather. It is a time when agricultural cycles wind down, harvest begins, and nature begins to turn inward. Sharad Navratri is timed to harness this transition.

Ashadha Gupt Navratri aligns approximately with the Summer Solstice (June‑21). This is the time of maximum solar intensity, longest day, maximum external energy. It often coincides with onset of monsoon in many parts of India, a shift from dry to wet, hot to more moderated climate, which has its own effects on human physiology and environment. Observing austerities or inward practices during or around this time can be seen as a way to counterbalance external excess and to harness solar power for internal transformation.

Magha Gupt Navratri falls around winter (January‑February), closely related to the Winter Solstice (December‑21). After the shortest days, with cold and dark, the trend begins slowly toward lengthening daylight and warmth. It is a time when many parts are adjusting to cold, low metabolism, immune challenges, etc. Using this period for introspection, purification and spiritual practices aligns one’s cycle with nature’s slow rebirth.

Thus the four Navratris fall, or are intended to fall, near times of maximal change in the natural environment — the “junctions” or “sandhis”: transitions in solar intensity, temperature, light, moisture, climate.

Physiological and Environmental Implications of Equinox/Solstice Transitions

The equinoxes and solstices are more than just astronomical curiosities; they have real effects on climate, seasons, plant and animal life, and hence human beings. Around equinoxes and solstices, changes in sunlight exposure led to shifts in circadian rhythms: hormonal cycles tied to melatonin, serotonin, vitamin‑D synthesis, immune function, mood (e.g. Seasonal Affective Disorder) are all influenced by day length and light intensity. Temperature swings and changes in humidity challenge immune systems; in transitional weather, there is greater incidence of respiratory illnesses, viral infections, fungal growth, etc. Traditional medical systems like Ayurveda recognize that at such junctions, “vyādhis” (diseases) tend to increase. Fasting, regulating diet, rest, and other awareness‑practices are traditionally prescribed in these “sandhi” (junction) times.

Agriculture also depends on these transitions: sowing, harvesting, monsoon onset or withdrawal, crop dormancy or regrowth; these in turn affect social rhythms, food availability, workload, sleep patterns. Human social life, festivals, gatherings, travel, etc., often cluster around post‐harvest or climatic ease periods. Effects on outer nature feed into human bodies and psyches. The mental stressors from extreme heat, cold, humidity, dryness are mitigated when society aligns some practices to these transition periods. The full Navratris tend to align with equinoxes where conditions are more moderate, to celebrate, rejoice, express public worship; the Gupt Navratris align with more extreme points (solstices), more inward focus.

Symbolic, Psychological and Spiritual Meanings

Beyond the external, seasonal, environmental and physiological, the equinoxes and solstices carry symbolic weight. The equinoxes represent balance — light and darkness are equal; energy is neither overwhelmingly external (light) nor overwhelmingly internal (dark). Psychologically, these are times when balance in life is easier to observe: when neither the external world dominates nor the internal world is completely shut down. The spiritual traditions see equinox periods as excellent for external worship, for community, for action, for rejoicing, because one’s inner and outer states can more easily be stabilized.

Solstices, by contrast, represent extremes. The winter solstice (longest night) represents darkness, stillness, contraction, rest, dormancy. The summer solstice (longest day) represents maximum external energy, maximum solar force, but also potential for exhaustion, for imbalance if one lives only outwards. These extremes in nature mirror extremes in inner life: when external activity is maximal or minimal, internal practices are required to bring balance, purification, introspection. It is significant that Gupt Navratri fall around those times: the internal, secret work, austerities, silence, or inward spiritual discipline correspond well to the external conditions. The Mahashakti Navratri in equinox periods allow for outward observance, communal worship, public joy, expressive devotion.

In Hindu mythology and Puranic literature, Goddess Durga or Devi in her various forms is invoked during Navratri as the power (Shakti) that overcomes chaos, ignorance, evil. These myths often contain symbolic themes of overcoming darkness, transformation, rebirth, victory of light, which resonate with the equinoxes and solstices: the dark to light, the light to dark, the balance, the extremes. The timing ensures that the mythic symbolism is not just abstract but anchored in lived, natural cycles.

How the Navratri Observances Harness the Equinox/Solstice Effects

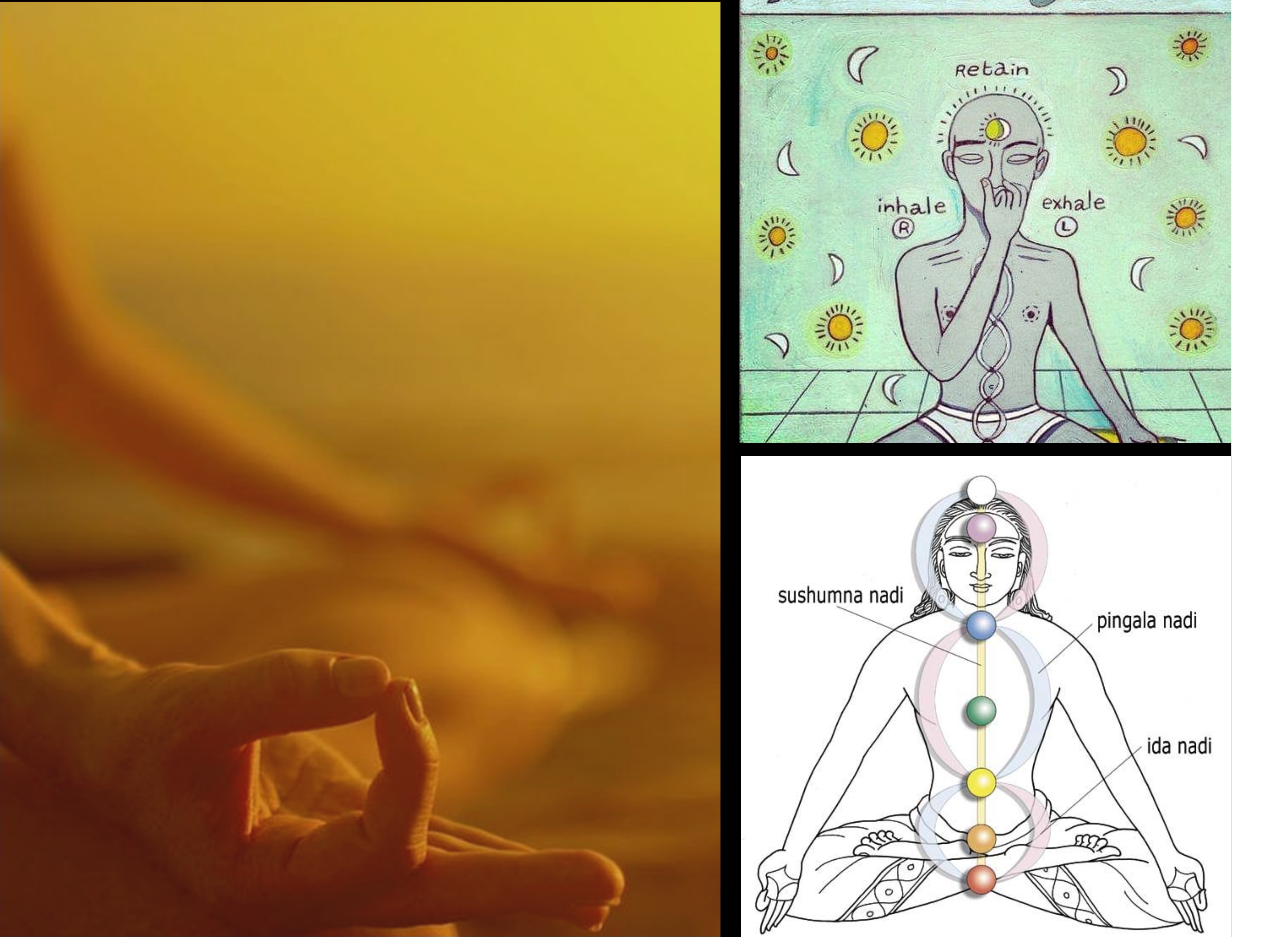

Traditional practices associated with Navratri — fasting or reduced, sattvic diets; early rising; increased worship; meditation; cleansing rituals; sometimes silence; abstention from certain behaviors — all serve to align the body‑mind more gently with the outer changes in climate, daylight, and ambient energy.

During equinox periods (full Navratris) as day and night are in balance, the body’s circadian rhythms may be more in flux; thus diet moderation helps prevent overreactions (e.g. digestive issues, seasonal illnesses). The external energy is more benign, making communal worship and celebration less taxing. At solstice times (Gupt Navratris), with extremes, the temperamental volatility of body and mind might be higher—heat, cold, or sudden change. Thus inward observances help reduce stress, prevent disease, bolster immune resilience, and maintain inner equilibrium.

Moreover, the change in solar declination and altitude also affects exposure to UV, variation in heat load, moisture in the air, wind and atmospheric pressure. Metabolic demands change; water intake, rest needs, etc., shift. Lungs, skin, and eyes are sensitive to these changes. The traditional practice of Bathing, oil massage, garbhopan, etc. before or during these periods helps maintain the integumentary and circulatory systems. Whether explicitly understood in ancient times or not, these practices seem to act like seasonal adjustments, much as we today adjust heating, clothing, diet, sun exposure.

Spiritually, many practitioners report that periods around equinox and solstice feel more potent for meditation, mantra, worship — perhaps because natural shifts in light, temperature, transitions in environmental stimuli reduce distraction or heighten awareness. Twenty first‑century psychology also recognizes that changes of season often provoke reflection, mood shifts, interest in change, which makes them opportune periods for spiritual resolution, resetting habits, performing vows or commitments, and renewal.

Historical and Scriptural Evidence

Scriptures like the Puranas, the Devi Mahatmya, and others mention Navratri in association with the brighter half of lunar months (Shukla Paksha) and with seasonal markers. While exact match to equinox or solstice dates may vary due to calendrical complexities (lunisolar calendar, regional variation, precession of equinoxes, local climate differences), many texts and traditions affirm that Sharadiya Navratri is near the September equinox and that Vasant/Chaitra Navratri is near the March equinox.

In addition, several modern articles, studies and practitioners in Ayurveda and Hindu spiritual traditions point out that diseases tend to spike during “sandhi kaal” (seasonal junctions, i.e. near equinoxes/solstices), and recommend dietary adjustments, fasting, mental discipline, purification rituals during those times. These practices are thought not only mythological but empirical: over centuries people observed that changes in seasons align with change in illness patterns, changes in vitality, changes in mood and mental clarity.

Integrative Reflection: Bringing Together All Four Navratris

Considering all four Navratris in light of equinoxes and solstices offers a cyclical view of spiritual life through the year. The cycle begins with Vasant/Chaitra Navratri, around the spring equinox, a time of rebirth. Nature is awakening; daylight is lengthening. It is fitting that worship of Durga begins anew, recognizing cycles of ending and beginning, encouraging devotees to plant seeds (literal or symbolic) of virtues, purification, growth.

Mid‑year, Ashadha Gupt Navratri around the summer solstice invites a turning inwards even in the season of maximum external energy. Because sunlight, heat, and environmental load are high, the body and mind benefit from restraint, rest, purification, and avoidance of overindulgence. Spiritual practice here is less outward display, more inner discipline, reflection, possibly secret or personal.

The cycle moves toward Sharadiya Navratri with the autumn equinox. After the external intensity and the monsoon’s tumult, the world is calmer, the climate is more moderate. Nature yields harvests; outward thanks and celebration come. This is the major festival time, with public worship, as the external and internal are again more harmonized. The mood is often of gratitude, triumph, generosity, artistic expression.

Then comes Magha Gupt Navratri around the winter solstice, when day is shortest, cold is strongest, darkness is more prevalent. This is the time for inner work: letting go, introspecting, retreating, restoring energy, reflecting on mortality, on impermanence, on inner potential. Silence, austerity, purification, perhaps fewer external rituals, more internal spiritual focus.

This cyclical movement ensures that the devotee’s spiritual life is not flat but responsive to nature’s rhythm. It ties one’s life, physical and psychological, to the rhythms of the planet, integrating body, environment, mind, and spirit in harmony. Instead of fighting against seasonal shifts or cultural shifts, one lives with them, aligning one’s spiritual observances to astronomical transitions.

Challenges: Calendrical Variations, Local Climates, Precession

While the ideal mapping of Navratris to equinox and solstice is compelling, there are complications. Hindu calendars are lunisolar, meaning months are determined by lunar phases but also adjusted with solar corrections (intercalary months etc.). Hence, exact dates of Navratri shift somewhat each year. Local climate conditions (latitude, altitude, monsoon timing etc.) differ greatly, so what feels like a “cold winter solstice” in one region may have very different sensory reality elsewhere. Precession of the equinoxes (a slow shift in Earth’s axial alignment over thousands of years) changes the background astronomical references over time. Also, the ancient texts may have been written when equinoxes and solstices had slightly different timings relative to lunar months. Thus, practitioners often interpret Navratri in light of local and temporal circumstances.

These variations do not negate the pattern; rather they show that the tradition is flexible and tuned to local ecological rhythms as well as astronomical ones. The symbolic and physiological benefits endure even if the dates do not perfectly match equinox/solstice in a given year.

Scientific Observations and Modern Research

Modern science has confirmed many of the phenomena that traditional observances seem to anticipate. Studies confirm that circadian rhythms are sensitive to day length and light intensity; immune function, hormonal regulation, mood disorders respond to changes in light and temperature. The field of chronobiology has demonstrated that seasonal affective disorder, shifts in sleep patterns, metabolism, appetite and energy often correspond to seasonal transition points. Ayurveda and modern integrative medicine note that fasting or reduced calorie intake, especially in periods when digestion naturally slows (winter) or when environmental stress is higher (summer), can help reduce oxidative stress, improve metabolic efficiency, detoxify, and reset various physiological rhythms.

Epidemiological data often show seasonal peaks of various ailments (e.g. respiratory infections in winter, heat exhaustion in peak summer, fungal infections after rains etc.). Traditional wisdom of observing certain festivals or fasts around equinox/solstice may work in part because they force behavioral changes (diet, sleep, exposure to elements etc.) in those critical transition periods.

Synthesis: How the Four Navratris Capture Natural Cycles for Human Flourishing

Bridging all of the above, one can see that the four Navratris are not mere religious festivals but more like markers built into the calendar to help human beings periodically tune themselves: physically, mentally, spiritually, socially, to nature's pulses. They provide pauses in the year where people are encouraged to cleanse, reflect, recalibrate.

During Vasant Navratri, people are encouraged to welcome growth, initiate new projects, shed old burdens, much as nature is re-greening.

During Ashadha Gupt Navratri, with solar energy at peak but environmental stress also high, inward containment, discipline helps manage internal and external stress.

At Sharadiya Navratri, as balance returns, it is time for joyous expression, public worship, harvest, creativity, and outward sharing.

In Magha Gupt Navratri, as darkness and quiet deepen, introspection, letting‑go, internal purification take precedence.

These rhythms serve not only spiritual symbolism but promote health: stabilizing circadian and seasonal rhythms, reducing stress on immune systems, improving mental health by giving structure to the year, supporting social cohesion through shared observances, creating psychological markers of renewal and rest.

Conclusion

The four Navratris — two full (Mahashakti) and two Gupt (secret) — are deeply interwoven with the natural cycles defined by equinoxes and solstices. Each Navratri corresponds roughly to one of those astronomical transition points, and the practices associated with each align with the external environmental, physiological, and psychological challenges and opportunities that those transitions bring. From spring’s reawakening to summer’s intensity, harvest’s balance, and winter’s inwardness, Navratri provides a cyclical scaffold for human life: purification, renewal, celebration, introspection.

Although exact calendrical alignment may shift—due to regional climate, lunar vs solar calculations, precession and historical change—the underlying pattern holds. Observing Navratri with awareness of its connection to equinox and solstice helps deepen its meaning. It becomes not only a festival of myth and devotion, but also one of attunement with nature, health, season, and cosmic rhythm.

In essence, Navratri can be understood scientifically as periods chosen in natural time when the Earth undergoes significant transitions; spiritually as opportunities to harness those transitions; culturally as communal markers of time that help anchor human life in larger celestial cycles; psychologically as moments for renewal and rebalancing. Recognizing this integrated dimension makes the celebration richer, more grounded, and more healing, not only for the individual but for community and environment.

- 19 min read

- 0

- 0