- Visitor:48

- Published on:

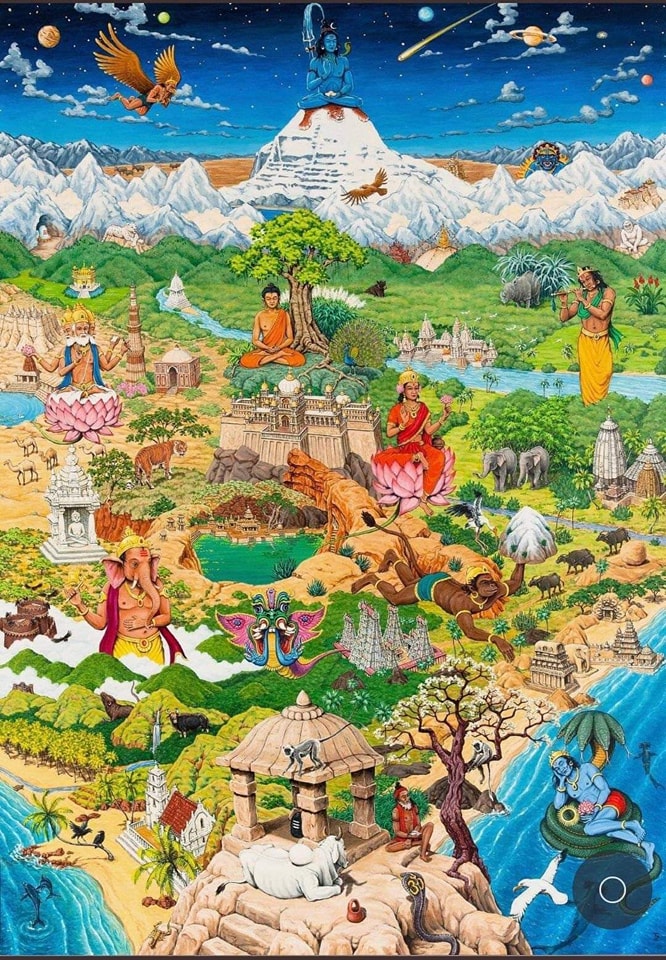

The Hindu Sikh Cleavage: Story of British Machination

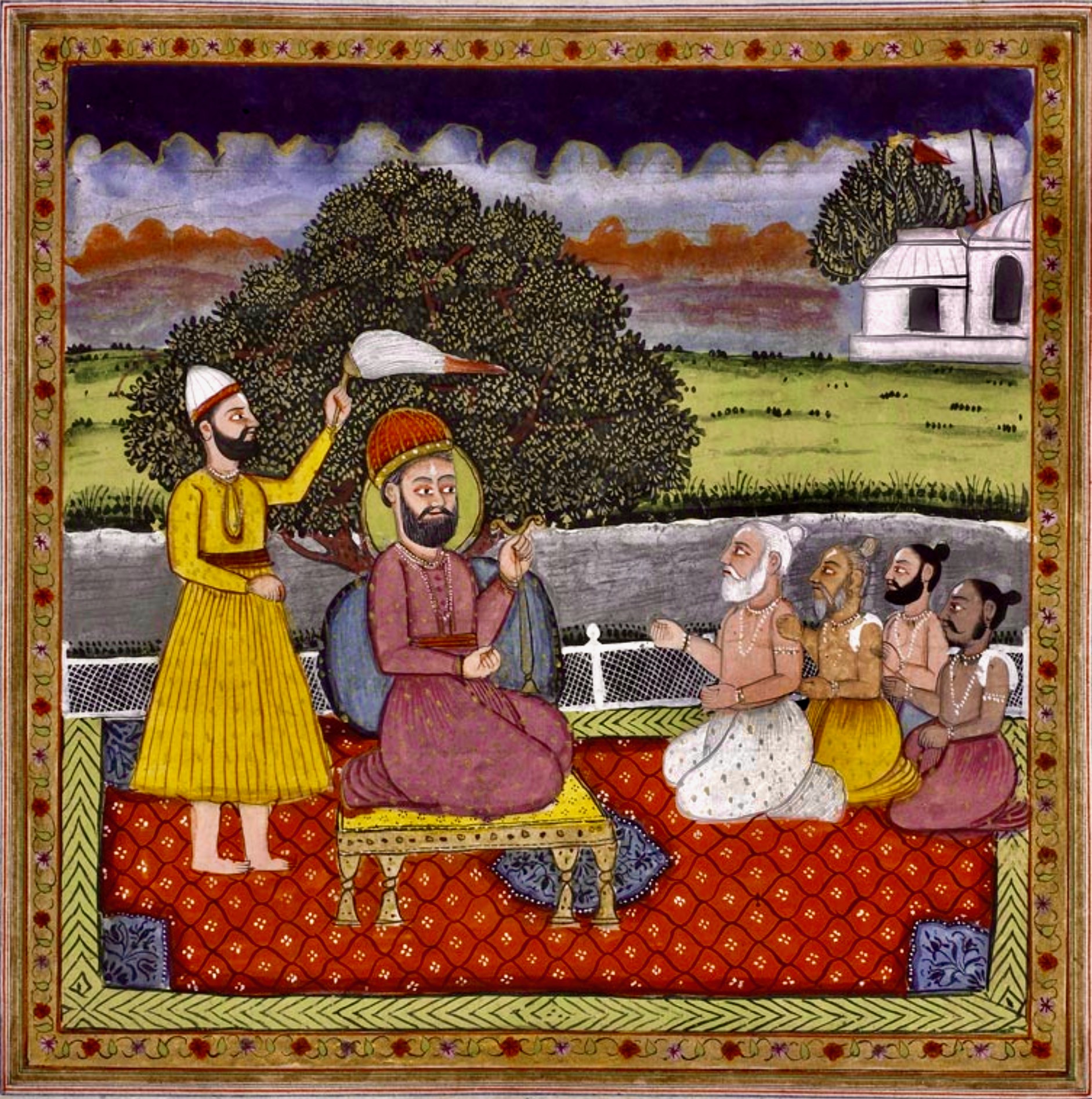

To fulfil a certain need of the hour, Guru Govind Singh preached the gospel of the Khalsa, the pure of the elect. Those who joined his group passed though a ceremony known as Pahul, and to emphasize the martial nature of their new vocation, they were given the title of Singh or “Lion”. Thus began a sect which was not based on birth but which drew its recruits from those who were not Khalsa by birth. It was almost wholly manned by the Hindus.

To fulfil a certain need of the hour, Guru Govind Singh preached the gospel of the Khalsa, the pure of the elect. Those who joined his group passed though a ceremony known as Pahul, and to emphasize the martial nature of their new vocation, they were given the title of Singh or “Lion”. Thus began a sect which was not based on birth but which drew its recruits from those who were not Khalsa by birth. It was almost wholly manned by the Hindus.

Military organization has taken different forms in different countries at different times. The Khalsa was one such form thrown up by a people weak in arms but strong in determination. This form worked and the people of the Punjab threw away the Mughal rule. But fortunes change; in 1849, the British took over the Punjab. The old-style Khalsa was no longer possible and the recruitment to it almost ceased.

The Punjab administration report of 1851-52 observes: The Sacred tank at Amritsar is less thronged than formerly, and the attendance at the annual festival is diminishing yearly. The initiatory ceremony for adults is now rarely performed”.

Not only did the fresh recruitment stop, but also a new exodus began. The same report says that people leave the Khalsa and “join the ranks of Hinduism whence they originally came and bring up their children as Hindus.”

The Phenomenon continued unabated. The administration report 1854-55 and 1855-56 finds that “now that the Sikh commonwealth is broken up, people cease to be initiated into Sikhism and revert to Hinduism.” At about this time, a census was taken. It revealed that the Lahore division which included Manjha, the original home of the Sikhs, had only 200,000 Sikhs in a population of three million. This exodus may account at least partly for this small number.

Original Status

The development raised no question. To those who were involved, this was perfectly in order and natural. Nobody was conscious of violation of any code. Hindus were Sikhs and Sikhs were Hindus. The distinction between them was functional, not fundamental. A Sikh was a Hindu in a particular role. When under the changed circumstances he could not play that role, he reverted to his original status. The government of the day admitted that “modern Sikhism was little more than a political association, formed exclusively from among Hindus, which men would join or quit according to the circumstances of the day.”

This development in accord with Indian reality was not liked by the British. They considered it as something “to be deeply deplored, as destroying a bulwark of our rule”.

Imperialism thrives on divisions and it sows them even where they do not exist. The British government invited one Dr. E. Trumpp, a German Indologist, to look at Sikh scriptures and prove that their theology and cosmology were different from those of the Vedas and the Upanishads. But he found nothing in them to support this view. He found Nanak a “through Hindu, his religion “a pantheism, derived directly from Hindu sources.’ In fact, the influence of Islam on subsequent Sikhism was, according to him, negative. “It is not improbable that the Islam had a great share in working silently these changes, which are directly opposed to the teachings of the gurus”, he says.

However, to please his clients, he said the external marks of the Sikhs separated them from the Hindus and once these were lost, they relapsed into Hinduism. Hence, Hinduism was a danger to Sikhism and the external marks must be preserved by the Sikhs at all costs. Precisely because there was a fundamental unity, the accidental difference had to be pushed to the utmost and made much of.

From onwards, “Sikhism in danger,” became the cry of many British scholar-administrators. Lepel Henry Griffen postulated that Hinduism had always been hostile to Sikhism and even socially the two had been antagonistic. One M.A. Macauliffe, a highly placed British administrator, became the loudest spokesman of this thesis. He told the Sikhs that Hinduism was like a “boa constrictor” of the Indian forests, which “winds its opponents… and finally causes it to disappear in its capacious interior”. The Sikhs “may go that way”, he warned.

Prophecies Invented

He was pained to see that the Sikhs regarded themselves as Hindus which was, “in direct opposition to the teachings of the gurus”. He put words into the mouth of the gurus and invented propheoies by them which anticipated the advent of the white race to whom the Sikhs would be loyal. He described “the pernicious effects of the upbringing of Sikh youths in a Hindu atmosphere. These youths, he said, “are ignorant of the Sikh religion and or its Prophecies in favor of the English and contract exclusive customs and prejudices to the extent of calling us Malechhas or persons of impure desires, and inspire disgust for the custom and habits of Christians.”

It was a concerned effort in which the officials, the scholars and the missionaries all joined. In order to separate the Sikhs, they were even made into a sect of Islam. For example, one Thomas Patrick Hughes, who had worked as a missionary for twenty years in Peshawar, edited the Dictionary of Islam.’

The work itself is scholarly but, like most European scholarships, it had a colonial inspiration. The third biggest article in this work, after Muhammad and the Quran, is on Sikhism. It devotes seven pages to the Shias, but eleven and half pages to the Sikhs! Probably, the editor himself thought it rather excessive for he offers an explanation to the orientalists who “may, perhaps, be surprised to find that Sikhism has been treated as a sect of Islam.” Indeed, it is surprising to the non-orientalists too. For, it must be a strange sect of Islam where the word ‘Muhammad’ does not occur even once in the writings of its founder, Nanak. But the inclusion of such an article “in the present work seemed to be most desirable,” as the editor says it was a policy matter.

The influence of scholarship is silent, subtle and long-range. Macauliffe and others provided categories which became the thought-equipment of subsequent Sikh intellectuals. But the British government did not neglect the quicker administrative and political measures. They developed a special army policy which gave results even in the short run. While they disarmed the nation as a whole, they created privileged enclaves of what they called martial races.

The British had conquered Punjab with help of Poorabiya soldiers, many of them Brahmins, but they played a rebellious role in 1857; so the British dropped them and sought other elements. The Sikhs were chosen.

The 1855, there were only 1,500 Sikh soldiers, mostly Mazhabis; in 1910, there were 33,000 out of a total 1,74,000 this time mostly Jats – just a little less than one-fifth of the total army strength. Their very recruitment was calculated to give them a sense of separateness and exclusiveness. Only such Sikhs were recruited who observed the marks of the Khalsa.

They were sent to receive baptism according to the rites prescribed by Guru Govind Singh. Each regiment had its own granthis. The greetings exchanged between the British officers and the Sikh soldiers were “Wahguruji ka Khalsa! Wahguruji Ki Fateh.” A secret C.I.D. memorandum, prepared by D. Petrie, Assistant Director, Criminal Intelligence, Government of India (1911), says that “every endeavor has been made to preserve them (Sikh Soldiers) from the contagion of idolatry,” a name the colonial-missionaries gave to Hinduism. Thanks to these measures, the “Sikhs in the Indian army have been studiously nationalized,” Macauliffe observed. About the meaning of this “nationalization”, we are left in no doubts, Petrie explains that it means that the Sikhs were “encouraged to regard themselves as a totally distinct and separate nation.” No wonder, the British congratulated themselves and held that the “preservation of Sikhism as separate religion was largely due to the action of the British officers”, as a British administrator put it.

Political level

The British also worked on a more political level. Singh Sabhas were started, manned mostly by ex-soldiers. These worked under Khalsa Diwans established at Lahore and Amritsar. Later on in 1902, the two diwans were amalgamated into one body, chief Khalsa diwans, providing political leadership to the Sikhs. They all wore the badge of loyalty to the British. As early as 1872, the loyal Sikhs supported the cruel suppression of the Namadhari Sikhs who had started a swadeshi movement. They were described as a “wicked and misguided sect.” the same forces described the Ghadarites in 1914 as “rebels” who should be dealt with mercilessly.

These organizations also spearheaded the movement for the de-Hinduzation of the Sikhs and preached that the Sikhs were distinct from Hindus. Anticipating the Muslim League, they represented to the British government as far back as 1888 that they be recognized as a separate community. They expelled the Brahmins from the Harmandir, where they worked as priests. They also threw out the idols of “Hindu” gods from this temple which were installed there. We do not know what these gods were and how “Hindu” they were, but most of them are adoringly mentioned in the poems of Guru Nanak. This was meant to impress the British. Hitherto, the Brahmins presided over different Sikh ceremonies which were the same as those of Hindus. There was now a tendency to have separate rituals. In 1909, the Ananda Marriage Act was passed.

Thus the seed sown by the British began to bear fruit. In 1898, Kahan Singh, the chief minister of Nabha and a pacca loyalist, wrote a pamphlet: Hum Hindu nahin hain (we are not Hindus). This note has not lacked a place in subsequent Sikh writings and politics, leading eventually in our own time to an intransigent politics and terroristic activities. But that the Sikhs learn their history from the British is not peculiar to them. We all do it.

The British played their game as best as they could, but they did not possess all the cards. The Hindu-Sikh ties were too intimate and numerous and these continued without much strain at the grass-root level. Only a small section maintained that there was a “distinct line of cleavage between Hinduism and Sikhism”; but a large section, as the British found, “favors, or at any rate views with indifference the reabsorption of the Sikhs into Hinduism”. They found it sad to think that very important classes of Sikhs like Nanak Panthis or Sahajdharis did not even think it “incumbent on them to adopt the ceremonial and social observances of Govind Singh.” And did not “even in theory, reject the authority of the Brahmins.”

The glorification of the Sikhs was welcome to the British to the extent it separately them from the Hindus, but it had its disadvantages too. Mr. Petrie found it a “constant source of danger,” something which tended to give the Sikhs a “wind in the head”. Sikh nationalism once stimulated refused British guidance and developed its own ambitions. The neo nationalist Sikh thought of a glorious past and had dreams of a glorious future, but neither in his past nor in his future “was there a place for the British officer,” as a British administrator complained. Any worth wide Sikh nationalism was incompatible with loyalty to the British. When neo-nationalists like Labh Singh spoke of the past “sufferings of the Sikhs at the hands at the Hands of the Muhammadans,” the British found in the statement a covert reference to themselves. When they admired the gurus for their devotion to religion and their disregard for life”, the British heard in it a call to sedition.

Contemptuous View

The Sikh nationalism was meant to hurt the Hindus, but in fact it hurt the British. For what nourished Sikh nationalism also nourished Hindu nationalism. The glories of Sikh gurus are part of the glories of the Hindus, and these have been sung by poets like Tagore and others. On the other hand, as Christians and as rulers, the British could not go very far in this direction. In fact, in their more private consultations, they spoke contemptuously of the gurus. Mr. Petrie considered Guru Arjun Singh as “essentially a mercenary”, who was “prepared to fight for or against the Moghul as convenience or profit dictated”; he tells us how “Tegh Bahadur, as an infidel, a robber and a rebel, was executed at Delhi by the Moghul authorities.” As imperialists, they naturally sympathized with the Moguls and shared their viewpoint.

Even during the heydays of Sikh loyalties to the British, there were many rebellious voices. One Baba Nihal Singh wrote (1885) a book entitled Khurshaid-I-Khalsa, which “dealt in an objectionable manner with the British occupation of the Punjab.” When Gokhale visited Punjab in 1907, he was received with great enthusiasm by the students of the Khalsa College, an institution started in 1892 specifically to instill loyalty to the British in the Sikh youth. The horses of his carriage were taken out and it was pulled by the students. He spoke from the college Dharmashala from which the Granth Sahib was specially removed to make room for him. It was here that the famous poem, “Pagri Sambhal, O Jatta” was first recited by Banke Dayal, editor of Jhang Sayal; it became the bettle-song of the Punjab revolutionaries.

There was a general awakening which could not but affect the Sikh youth too. Mr. Petrie observes that the “Sikhs have not been, and are not, immune from the disloyal influences which have been at work among other sections of the populace.”

A most powerful voice of revolt came from America where many Sikh Jat ex-soldiers had settled. Many of them had been in Hong Kong and other places as soldiers in the British regiments. There they heard of a faraway country where people were free and prosperous. Their imagination was fired.

The desire to emigrate was reinforced by very bad conditions at home. The drought of 1905-07 and the epidemic in its wake killed two million people in the Punjab. In the first decade of this century, the region suffered a net decreases in population. Due to new fiscal and monetary policies and new economic arrangements, there was a large-scale alienation of the land from the cultivators and hundreds of thousands of the poor and middle peasants were wiped out or fell into debt.

Sorry Status

Many of them migrated and settled in British Columbia and Vancouver. Here they were treated with contempt. They realized for the first time that their sorry status abroad was due to their colonial status at home. They also began to see the link between India’s poverty and British imperialism. Thus many of them, once loyal soldiers who took pride in this fact, turned rebels. They raised the banner of Indian nationalism and spoke against the Singh Sabhas, the chief Khalsa-Diwans and Sardar Bahadurs at home. They spoke of Bharat-Mata: their heroes were patriots and revolutionaries from Bengal and Maharashtra, and not their co-religionists in the Punjab whom they called the “traffickers of the country.”

The earlier trends, some of them mutually opposed, became important components of subsequent Sikh politics. The pre-war politics continued under new labels at an accelerated pace. During this period, social fraternization with the Hindu continued as before, but politically the Sikh community became more sharply defined and acquired a greater group consciousness.

In the pre-war period, the attempt was made to de-Hinduize Sikhism; now it was also Khalsaised. Hitherto, the Sikh temples were managed by non-Khalsa Sikh, mostly by Udasis; now these were taken out of their hands. Khalsa activists, named Akalis, “belonging to the immortals”, moved from place to place and occupied different Gurudwāras. These eventually came under the control of the Shiromani Gurudwāras Prabandhak Committee in 1925. From this point onwards, Sikh religion who controlled the resources of the temples controlled Sikh politics. The SGPC Act of 1925 defined Sikhs in a manner which excluded the Sahajdharis and included only the Khalsa. The SGPC Akalis, Jathas became important in the life of the Sikh community. Non-Khalsa Sikhs became second-grade members of the community.

The period of freedom struggle was not all idealism and warm-hearted sacrifices. There were many divisive forces, black sheep, and tutored roles. But the role of the Akalis was not always negative. They provided a necessary counterweight to the League politics. On the eve of independence, the League leaders tried to woo the Akalis, but, by and large, they were spurned. For a time, some Akalis, leaders played with the idea of a separate Khalistan, and the British encouraged them to present their case. But they found that they were in a majority only in two tehsils and the idea of a separate state was not visible.

Independence came accompanied by division of the country and large displacement of population. The country faced big problems but managed to keep above water. We were also able to retain democracy. But just when we thought we had come out of the woods, divisive forces which lay low for a time reappeared. The old drama with new cast began to be enacted again.

The atmosphere provided hothouse conditions for the growth of divisive politics. Our Sikh brothers too remembered the old lesson, never really forgotten by them, taught them by the British, that they were different. McAuliffe’s works published in the first decade of the century were reissued in the sixties. More recent Sikh scholars wrote histories of the Sikhs which were variations on the same theme. In no case, they provided a different vision and perspective.

Extreme Slogans

Under the pressure of this psychology, grievances were manufactured; extreme slogans were put forward with which even moderate elements had to keep pace. In the last few years, even the politics of murder was introduced. Finding no check, it knew not where to stop; it became a law into itself; it began to dictate, to bully. Campus came up in India as well as across the border, where young men were taught killing, sabotage and guerilla warfare. The temple at Amritsar became an arsenal, a fort, a sanctuary for criminals. This grave situation called for necessary action which caused some unavoidable damage to the building. When this happened the same people who looked on the previous drama, either helplessly or with an indulgent eye, felt outraged. There were protest meetings, resolutions, and committees for the suspects apprehended, and even calls and vows to take revenge. The extremists who died became martyrs; the Jawans who gave up their lives in performing a patriotic duty were forgotten. There were two standards at work; there was a complete lack of self-reflection even among the more moderate and responsible Sikh leaders.

However, all is not dark. The way the common Hindus and Sikhs stood for each other in the recent happenings in the Punjab and Delhi show how much in common they have. In a time so full of danger and mischief, this age-long unity proved the most solid support. But seeing what can happen, we should not take this unity for granted. We should cherish it, cultivate it, re-emphaze it. We can grow great together; in separation, we can only hurt each other.

(The Times of India, 20 December 1989)

[Source: Ram Swarup, Hinduism and Monotheistic Religions, pp. 311-320]

Center for Indic Studies is now on Telegram. For regular updates on Indic Varta, Indic Talks and Indic Courses at CIS, please subscribe to our telegram channel !

- 24 min read

- 1

- 0

.jpg)