- Visitor:30

- Published on:

Karma is Not Fate

In this excerpt, Will Durant, the world famous historian discusses the ideas of Karma and rebirth in Hindu philosophy. He also compares it with the notion of fate in the West and tells us how it is different from fate. This is an excerpt from “Our Oriental Heritage”, the first volume of the monumental history of the world by Will Durant.

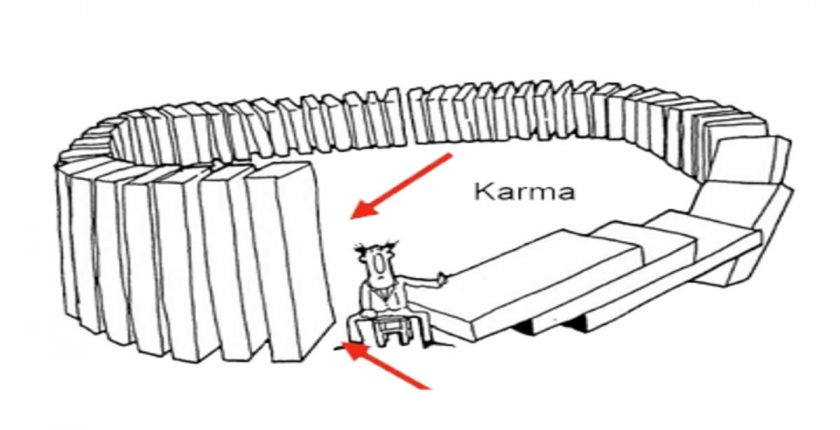

Life can be understood, says the Hindu, only on the assumption that each existence is bearing the penalty or enjoying the fruits of vice or virtue in some antecedent life. No deed small or great, good or bad, can be without effect; everything will out. This is the Law of Karma-the Law of the Deed-the law of causality in the spiritual world; and it is the highest and most terrible law of all. If a man does justice and kindness without sin his reward cannot come in one mortal span; it is stretched over other lives in which, if his virtue persists, he will be reborn into loftier place and larger good fortune; but if he lives evilly he will be reborn as an Outcaste, or a weasel, or a dog.

This law of Karma, like the Greek Moira or Fate, is above both gods and men; even the gods do not change its absolute operation; or, as the theologians put it, Karma and the will or action of the gods are one.” But Karma is not Fate; Fate implies the helplessness of man to determine his own lot; Karma makes him (taking all his lives as a whole) the creator of his own destiny. Nor do heaven and hell end the work of Karma, or the chain of births and deaths; the soul, after the death of the body, may go to hell for special punishment, or to heaven for quick and special reward; but no soul stays in hell, and few souls stay in heaven, forever; nearly every soul that enters them must sooner or later return to earth, and live out its Karma in new Incarnations.

Biologically there was much truth in this doctrine. We are the reincarnations of our ancestors, and will be reincarnated in our children; and the defects of the fathers are to some extent (though perhaps not as much as good conservatives suppose) visited upon the children, even through many generations. Karma was an excellent myth for dissuading the human beast from murder, theft, procrastination, or offertorial parsimony; furthermore, it extended the sense of moral unity and obligations to all life, and gave the moral code an extent of application far greater, and more logical, than in any other civilization.

Good Hindus do not kill insects if they can possibly avoid it; “even those whose aspirations to virtue are modest treat animals as humble brethren rather than as lower creatures over whom they have dominion by divine command.” Philosophically, Karma explained for India many facts otherwise obscure in meaning or bitterly unjust. All those eternal inequalities among men which so frustrate the eternal demands for equality and justice; all the diverse forms of evil that blacken the earth and redden the stream of history; all the suffering that enters into human life with birth and accompanies it unto death, seemed intelligible to the Hindu who accepted Karma; these evils and injustices, these variations between idiocy and genius, poverty and wealth, were the results of past existences, the inevitable working out of a law unjust for a life or a moment, but perfectly just in the end.

Karma is one of those many inventions by which men have sought to bear evil patiently, and to face life with hope. To explain evil, and to find for men some scheme in which they may accept it, if not with good cheer, then with peace of mind-this is the task that most religions have attempted to fulfill. Since the real problem of life is not suffering but undeserved suffering, the religion of India mitigates the human tragedy by giving meaning and value to grief and pain. The soul, in Hindu theology, has at least this consolation, that it must bear the consequences only of its own acts; unless it questions all existence it can accept evil as a passing punishment, and look forward to tangible rewards for virtue borne.

- 15 min read

- 0

- 0