- Visitor:17

- Published on:

Four Ways of Cooking

In this article, Michael Pollan discusses how there are basically four ways of cooking: grilling with fire, cooking with liquid, baking bread, and fermenting all sorts of things. And how they are based on four basic elements: fire, water, air and earth. It is with basically these four techniques that the world cooks its food. This is an excerpt from the book ‘Cooked’ by Michael Pollan.

Cooking—defined broadly enough to take in the whole spectrum of techniques people have devised for transforming the raw stuff of nature into nutritious and appealing things for us to eat and drink—is one of the most interesting and worthwhile things we humans do. This is not something I fully appreciated before I set out to learn how to cook.

But after three years spent working under a succession of gifted teachers to master four of the key transformations we call cooking—grilling with fire, cooking with liquid, baking bread, and fermenting all sorts of things—I came away with a very different body of knowledge from the one I went looking for. Yes, by the end of my education I got pretty good at making a few things—I’m especially proud of my bread and some of my braises.

But I also learned things about the natural world (and our implication in it) that I don’t think I could have learned any other way. I learned far more than I ever expected to about the nature of work, the meaning of health, about tradition and ritual, self-reliance and community, the rhythms of everyday life, and the supreme satisfaction of producing something I previously could only have imagined consuming, doing it outside of the cash economy for no other reason but love.

This book is the story of my education in the kitchen—but also in the bakery, the dairy, the brewery, and the restaurant kitchen, some of the places where much of our culture’s cooking now takes place. Cooked is divided into four parts, one for each of the great transformations of nature into the culture we call cooking. Each of these, I was surprised and pleased to discover, corresponds to, and depends upon, one of the classical elements: Fire, Water, Air, and Earth.

Why this should be so I am not entirely sure. But for thousands of years and in many different cultures, these elements have been regarded as the four irreducible, indestructible ingredients that make up the natural world. Certainly they still loom large in our imagination. The fact that modern science has dismissed the classical elements, reducing them to still more elemental substances and forces—water to molecules of hydrogen and oxygen; fire to a process of rapid oxidation, etc.—hasn’t really changed our lived experience of nature or the way we imagine it. Science may have replaced the big four with a periodic table of 118 elements, and then reduced each of those to ever-tinier particles, but our senses and our dreams have yet to get the news.

To learn to cook is to put yourself on intimate terms with the laws of physics and chemistry, as well as the facts of biology and microbiology. Yet, beginning with fire, I found that the older, prescientific elements figure largely—hugely, in fact—in apprehending the main transformations that comprise cooking, each in its own way. Each element proposes a different set of techniques for transforming nature, but also a different stance toward the world, a different kind of work, and a different mood.

Fire being the first element (in cooking anyway), I began my education with it, exploring the most basic and earliest kind of cookery: meat, on the grill. My quest to learn the art of cooking with fire took me a long way from my backyard grill, to the barbecue pits and pit masters of eastern North Carolina, where cooking meat still means a whole pig roasted very slowly over a smoldering wood fire.

It was here, training under an accomplished and flamboyant pit master, that I got acquainted with cooking’s primary colors—animal, wood, fire, time—and found a clearly marked path deep into the prehistory of cooking: what first drove our protohuman ancestors to gather around the cook fire, and how that experience transformed them. Killing and cooking a large animal has never been anything but an emotionally freighted and spiritually charged endeavor. Rituals of sacrifice have attended this sort of cooking from the beginning, and I found their echoes reverberating even today, in twenty-first-century barbecue. Then as now, the mood in fire cooking is heroic, masculine, theatrical, boastful, unironic, and faintly (sometimes not so faintly) ridiculous.

It is in fact everything that cooking with water, the subject of part II, is not. Historically, cooking with water comes after cooking with fire, since it awaited the invention of pots to cook in, an artifact of human culture only about ten thousand years old. Now cooking moves indoors, into the domestic realm, I delve into everyday home cookery, its techniques and satisfactions as well as its discontents. Befitting its subject, this section takes the shape of a single long recipe, unfolding step by step the age-old techniques that grandmothers developed for teasing delicious food from the most ordinary of ingredients: some aromatic plants, a little fat, a few scraps of meat, a long afternoon around the house. Here, too, I apprenticed myself to a flamboyant professional character, but she and I did most of our cooking at home in my kitchen, and often as a family—home and family being very much the subject of this section.

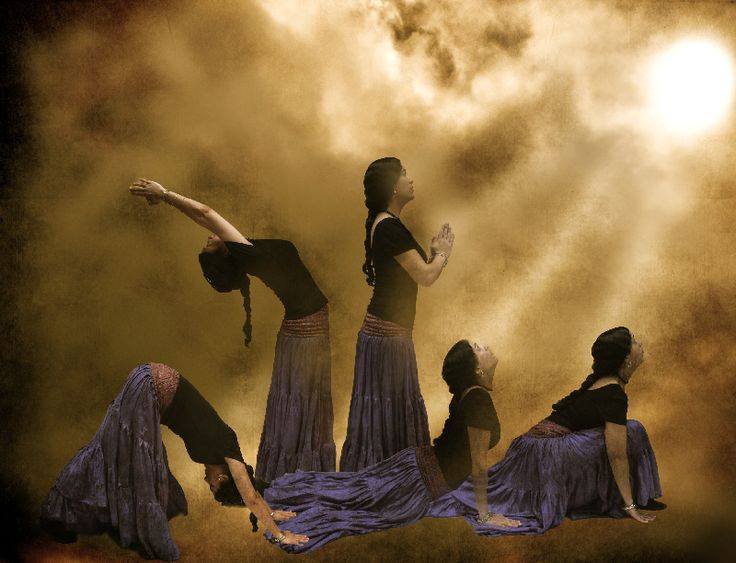

Part III takes up the element of air, which is all that distinguishes an exuberantly leavened loaf of bread from a sad gruel of pulverized grain. By figuring out how to coax air into our food, we elevate it and ourselves, transcending, and vastly improving, what nature gives us in a handful of grass seed.

The story of Western civilization is pretty much the story of bread, which is arguably the first important “food processing” technology. (The counterargument comes from the brewers of beer, who may have gotten there first.) This section, which takes place in several different bakeries across the country (including a Wonder Bread plant), follows two personal quests: to bake a perfect, maximally airy and wholesome loaf of bread, and to pinpoint the precise historical moment that cooking took its fatefully wrong turn: when civilization began processing food in such a way as to make it less nutritious rather than more.

Different as they are, these first three modes of cooking all depend on heat. Not so the fourth. Like the earth itself, the various arts of fermentation rely instead on biology to transform organic matter from one state to a more interesting and nutritious other state. Here I encountered the most amazing alchemies of all: strong, allusive flavors and powerful intoxicants created for us by fungi and bacteria—many of them the denizens of the soil—as they go about their invisible work of creative destruction.

This section covers the fermentation of vegetables (into sauerkraut, kimchi, pickles of all kinds); milk (into cheese); and alcohol (into mead and beer). Along the way, a succession of “fermentos” tutored me in the techniques of artfully managing rot, the folly of the modern war against bacteria, the erotics of disgust, and the somewhat upside-down notion that, while we were fermenting alcohol, alcohol has been fermenting us.

I have been fortunate in both the talent and the generosity of the teachers who agreed to take me in—the cooks, bakers, brewers, picklers, and cheese makers who shared their time and techniques and recipes. This cast of characters turned out to be a lot more masculine than I would have expected, and a reader might conclude that I have indulged in some unfortunate typecasting. But as soon as I opted to apprentice myself to professional rather than amateur cooks—in the hopes of acquiring the most rigorous training I could get—it was probably inevitable that certain stereotypes would be reinforced. It turns out that barbecue pit masters are almost exclusively men, as are brewers and bakers (except for pastry chefs), and a remarkable number of cheese makers are women. In learning to cook traditional pot dishes, I chose to work with a female chef, and if by doing so I underscored the cliché that home cooking is woman’s work, that was sort of the idea: I wanted to delve into that very question. We can hope that all the gender stereotypes surrounding food and cooking will soon be thrown up for grabs, but to assume that has already happened would be to kid ourselves.

Other article in this series can be read here:

- 8 min read

- 0

- 0