- Visitor:325

- Published on: 2025-04-03 11:51 am

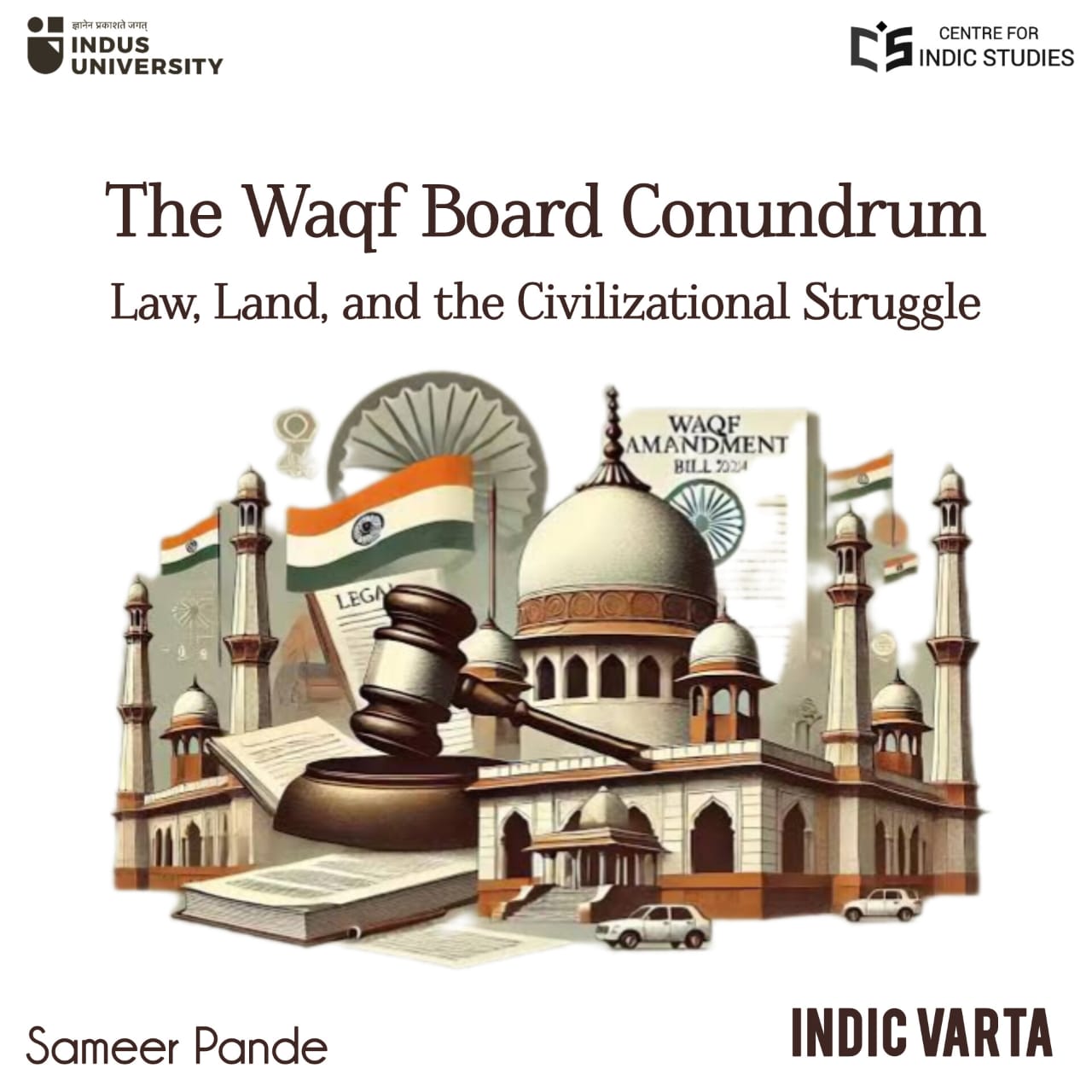

The Waqf Board Conundrum: Law, Land, and the Civilizational Struggle

Let’s get straight to it: do Islamic states have Waqf Boards? The answer is mostly no. Most Muslim-majority nations have either reformed or dismantled their waqf systems. Turkey, under Atatürk, nationalized waqf properties and put them under government control. Egypt and Tunisia did the same. Even Saudi Arabia, the epicentre of Islam, keeps waqf lands under strict state oversight. In contrast, India maintains a parallel legal system for waqf, where a self-regulated body controls vast amounts of land with minimal state intervention. Why? Because India, unlike Islamic states, never dared to touch the system after Partition. Instead, it codified and expanded waqf protections, granting it more autonomy than even some Sharia-compliant regimes. And you know why? The vote bank politics!

Land– the very foundation of civilization! Not just dirt and stones, but power, history, and identity! And in India, land has always been more than just property, it has been sacred, contested, and, at times, seized under legal pretexts. Yesterday, the 2nd of April, the Lok Sabha passed the Waqf (Amendment) Bill, 2025, throwing the spotlight once again on one of the most controversial and under-discussed aspects of land ownership in India. The bill, introduced by Union Minority Affairs Minister Kiren Rijiju, pushes for reforms in the Waqf Board structure, bringing non-Muslim members into the Central Waqf Council and granting the government authority to determine ownership of disputed waqf lands. The numbers tell their own story: 288 votes in favor, 232 against. Supporters call it a step towards transparency, a long-overdue check on corruption within Waqf Boards. Opponents see it as an attack on religious autonomy, an attempt to erode Muslim control over vast tracts of land.

But is this really just about transparency? Or is it about something deeper, the fundamental question of who owns land in India and how that ownership has been shaped, twisted, and codified over centuries? This is not just a legal debate; it is a civilizational one. From ancient Bharat to the Mughal era, from British land policies to post-independence legal battles, the issue of land, and who gets to claim it, has shaped the very contours of Indian history. The Waqf system, its rise, its legal entanglements, and its modern conflicts cannot be understood in isolation. The past is not dead. It is not even past.

The Question of Land in India

Land is not just about possession; it is about power. It dictates governance, shapes economies, and ensures cultural continuity. From the earliest Vedic texts to modern property laws, land has determined the fate of civilizations. Who owns it? Who controls it? And more importantly, who gets to decide?

Throughout Indian history, land ownership has evolved from a community-driven trust to state-backed authority and eventually to legal frameworks riddled with contradictions. The Waqf system, an institution introduced with Islamic rule, fundamentally altered traditional landholding patterns, creating permanent religious endowments that transcended dynastic shifts and legal reforms. Now, with the Waqf (Amendment) Bill, 2025, we are forced to revisit uncomfortable questions, Is Waqf land a parallel legal system? Does religious landholding contradict a secular state's authority? Is this debate really about faith, or is it about institutionalized power? This issue cannot be examined in isolation. It must be understood through the prism of history, law, and political economy, how land was perceived, how it was controlled, and how it became a battleground of civilizational struggle.

In ancient India, land was neither privately owned in the modern sense nor completely controlled by the ruler. It was a shared resource, administered through multiple layers of authority, Rashtra (kingdom), Janapada (nation-state), and Gram Sabha (village councils). The king was a Kshetrapati, the guardian, not the owner of the land. His duty was to ensure righteous distribution and prevent unlawful occupation. Land grants were common, particularly for educational purposes, giving rise to Devasvam (temple-owned land) and universities. These institutions ensured continuity of land control while being accountable to the community, rather than a centralized religious authority. But this equilibrium was disrupted with the arrival of Islamic rule. With the Delhi Sultanate and later the Mughals, the very foundation of landholding was redefined. Power was now concentrated in the hands of rulers who dictated ownership through systems like. Few systems were introduced as as Iqta, temporary land grants to nobles and military officers; Jagir, Feudal landholdings that were assigned and reassigned by the ruler; Waqf, A unique institution where land, once dedicated, became permanent religious property, untouched by royal or state authority.

The concept of Waqf created a parallel land governance system, where vast tracts of land were locked away from state control, becoming semi-autonomous religious estates. The Mughal emperors expanded and legitimized Waqf, granting enormous power to Islamic clergy, setting a precedent that outlived even the empire. When the British arrived, they were less interested in theological land ownership and more focused on taxable revenue streams. Their policies further reshaped the structure: The Zamindari system turned landlords into tax collectors, prioritizing profit over traditional land ethics. Recognizing Waqf’s legal and economic implications, the British codified it, bringing it under structured law while maintaining its religious immunity. Post-independence, The Waqf Act of 1954 and its subsequent amendments formalized this system within the Indian legal framework, effectively creating a state-backed religious landholding body. And now, in 2025, we are once again confronted with the same foundational questions: should religious institutions hold, govern, and profit from land without state oversight? Should historical anomalies dictate modern governance? Is this about land, law, or civilizational dominance? The debate is far from over. It has just begun.

Historical Origins of Waqf in Islamic History

The institution of waqf finds its roots in early Islamic civilization, where devout Muslims would dedicate properties for perpetual religious or charitable use. Once declared as waqf, these assets were considered inviolable, serving purposes such as funding mosques, educational institutions, and aiding the underprivileged. The irrevocability of waqf ensured that these properties remained beyond the reach of personal inheritance or state appropriation. In India, the waqf system gained significant prominence during the Mughal era. Emperors and nobility established extensive waqf estates, leading to the creation of vast religious endowments that wielded considerable influence over land distribution and societal structures. This period saw waqf becoming deeply embedded in the socio-economic fabric of the region.

The advent of British colonial rule introduced a new dimension to the administration of waqf properties. The British legal system sought to codify and regulate these endowments, leading to the enactment of laws aimed at overseeing waqf assets. Notably, the Mussalman Wakf Validating Acts of 1913 and 1930 were instrumental in legally recognizing waqf deeds and providing a framework for their governance. Following India's independence, the need for a comprehensive legal structure to manage waqf properties became evident. This led to the introduction of the Waqf Act in 1954, which established State Waqf Boards tasked with the administration and protection of waqf assets. Over the years, the Act has undergone several amendments to address emerging challenges and to enhance the efficiency of waqf management. Despite these legislative efforts, issues such as mismanagement, encroachment, and corruption have persisted, prompting ongoing debates about the effectiveness of the existing framework.

Today, Waqf Boards in India are among the country's largest landholders, overseeing approximately 600,000 registered properties that span over 800,000 acres. These assets include mosques, graveyards, schools, and commercial establishments, and even claims on old temples reflecting the extensive reach of waqf in the nation's land distribution. The vastness of waqf properties has inevitably led to numerous legal disputes concerning ownership and usage rights. A significant number of these cases are entangled in prolonged litigation, with thousands of disputes pending in various courts across the country. These conflicts often involve allegations of unauthorized occupation, fraudulent transfers, and challenges to the legitimacy of waqf claims. The judiciary, particularly the Supreme Court of India, has played a crucial role in adjudicating waqf-related disputes. In landmark rulings, the Court has emphasized that mere publication by a Waqf Board does not suffice to declare a property as waqf; due statutory processes, including proper surveys and dispute resolution mechanisms, are essential. These judgments underscore the necessity for meticulous adherence to legal procedures in waqf property declarations. Several high-profile cases have brought waqf properties into the national spotlight. Disputes over historical mosques, shrines, and other religious sites have often escalated into communal tensions, reflecting the sensitive nature of waqf-related conflicts. These cases highlight the intricate interplay between religious sentiments, legal frameworks, and property rights in India.

Issues with the Waqf Board

The administration of waqf properties has been marred by numerous challenges. First being the encroachments and documentation issues. A significant number of waqf properties have been subject to illegal encroachments, often exacerbated by inadequate documentation and record-keeping. The Sachar Committee Report (2006) highlighted that encroachments by government agencies and individuals had led to losses worth thousands of crores.

Second is the corruption allegations. There have been persistent allegations of corruption within Waqf Boards, including unauthorized sales and mismanagement of assets. Reports indicate that illegal sales of waqf land by corrupt board members, often at undervalued rates, have created complex landholding situations in various regions.

Third being the pending legal cases. The judicial system is burdened with a substantial backlog of waqf-related cases, reflecting the pervasive nature of disputes and the challenges in resolving them efficiently.

State vs. Religion: The Right to Interfere in Waqf Matters

The extent of state intervention in waqf affairs has been a contentious issue. While the government asserts its role in ensuring transparency and accountability, critics argue that excessive interference undermines religious autonomy. Judicial pronouncements have sought to balance these interests, emphasizing the need for lawful oversight without encroaching upon religious freedoms.

How Waqf Works: Control, Land Ownership, and Its Evolution in India

As discussed earlier, the waqf system is an Islamic endowment where a person donates land or property for religious or charitable purposes. Once a property is declared waqf, it becomes irrevocable, perpetual, and inalienable, meaning it cannot be sold, inherited, or repurposed for personal gain. Some terminology to understand the working of the Waqf. Waqif (Donor) is the person who dedicates the property; Mutawalli (Manager/Trustee) is the caretaker of the waqf property; Mauqūf‘alayh (Beneficiary) are those who benefit from the waqf (mosques, madrasas, hospitals, or the poor).

In India, waqf is regulated by the Central Waqf Council and State Waqf Boards, which manage waqf properties across the country. Waqf properties are under the direct control of State Waqf Boards, which function as quasi-governmental bodies. While these boards are recognized under Indian law, they primarily operate exclusively under Muslim control. Their composition is of the members of Waqf Boards who are Muslims, appointed by the state government but drawn from Muslim scholars, religious leaders, and institutions. Waqf Boards have the unilateral authority to declare any property as waqf land, and their decisions can only be challenged in Waqf Tribunals, not in regular courts. Waqf Boards generate income by leasing out properties, collecting rents, and through donations, often operating outside standard government oversight.

The Status of Muslim Land in India During Partition

Before Partition, Muslims controlled large tracts of land, both privately and through waqf institutions. However, after 1947, the situation changed dramatically. The land of Muslims who migrated to Pakistan. Their properties were taken over by the Indian government under the Enemy Property Act. These properties were not transferred to the Waqf Board but instead came under the control of the Custodian of Enemy Property for India (CEPI). The property of Muslims who stayed in India. Their waqf properties remained intact. Some waqf properties lost tenants and revenue streams as Muslim populations shifted. The government never nationalized waqf properties, and they remained exclusively in Muslim hands.

Government Recognition of Waqf Post-Partition. The Indian government, despite having abolished zamindari, continued to recognize waqf properties as separate from regular landholding systems. The Waqf Act of 1954 granted legal status and immunity to waqf properties, preventing them from being acquired by the government.

How Waqf Functions in Post-Independent India

Regarding the land acquisition powers, Waqf Boards can unilaterally declare land as waqf, often without contest. Disputes over these declarations cannot be directly challenged in civil courts but must go through Waqf Tribunals, making legal recourse difficult.

Waqf properties have grown significantly due to new land acquisitions and donations, making Waqf Boards one of the largest landholders in India. Unlike Hindu temple trusts or other religious bodies, waqf enjoys legal protection that prevents state takeover or redistribution. While Waqf Boards fall under the Ministry of Minority Affairs, they are largely self-regulated, leading to widespread allegations of corruption, illegal leasing, and mismanagement. Attempts to investigate or audit waqf land dealings have often met with resistance.

The ‘Uniqueness’ of Waqf in Indian Law

Unlike Hindu endowments, which are often managed by government-controlled Devasthanam Boards (such as the Tirupati Temple Board), Waqf remains under exclusive Muslim control. While Christian and Sikh institutions operate their own trusts, they do not enjoy the same legal immunities that waqf does. Attempts to reclaim or repurpose waqf land for public use often face legal roadblocks due to its perpetual and irreversible nature.

Conclusion is a parallel land system. The waqf system, originally rose from religious and charitable purposes, has evolved into a powerful land-controlling mechanism with significant socio-political implications. Unlike regular property, waqf land remains permanently locked, creating a unique and largely unchallenged parallel legal system. Given the vast and growing control of Waqf Boards, questions arise about accountability, fair land distribution, and the role of religious endowments in a secular state.

Waqf Boards in Other Countries: An Indian Exception?

Let’s get straight to it: do Islamic states have Waqf Boards? The answer is mostly no. Most Muslim-majority nations have either reformed or dismantled their waqf systems. Turkey, under Atatürk, nationalized waqf properties and put them under government control. Egypt and Tunisia did the same. Even Saudi Arabia, the epicentre of Islam, keeps waqf lands under strict state oversight. In contrast, India maintains a parallel legal system for waqf, where a self-regulated body controls vast amounts of land with minimal state intervention. Why? Because India, unlike Islamic states, never dared to touch the system after Partition. Instead, it codified and expanded waqf protections, granting it more autonomy than even some Sharia-compliant regimes. And you know why? The vote bank politics!

So, another important question is - is this a civilizational conflict? Land is not just real estate, it’s history, culture, and civilizational memory etched into geography. In every society, land is power. The sanatana concept of land is Dharmic, linked to duty, sacred geography, and shared community ownership (Gram, Rashtra, Janapada). Islamic waqf, however, is eternal and exclusionary, once land enters waqf, it remains locked forever in religious control. Western land laws, shaped by capitalism, prioritize private ownership and state regulation. So, is this just about property rights, or is it civilizational hegemony? Look at the recurring disputes, Mathura, Kashi, Bhojshala. The question is not merely who owns the land, but who defines the cultural and civilizational identity of the land.

Who Has Suffered from This System?

Let’s talk about the actual victims of waqf’s unchecked expansion. Hindus and Sikhs who find their temples and gurudwaras designated as waqf land. Yes, it’s happened, documented cases exist where centuries-old Hindu and Sikh religious sites were listed under waqf control. Poor and marginalized communities, tribals and Dalits, who have been evicted from their homes after Waqf Boards claimed their lands. Even Muslims who dare to question the corruption in Waqf Boards, many within the Muslim community have spoken about mismanagement, embezzlement, and political interference, but their voices rarely get mainstream attention.

So, what are the potential solutions? What can be done? Should waqf properties be brought under national heritage laws? If Hindu and Sikh temples are regulated by government-appointed trusts, why does waqf remain untouchable? Every Waqf Board transaction should be subject to public scrutiny and RTI (Right to Information) regulations. There is a need to rethink perpetuity. No land system should remain permanently locked; even Islamic nations have modified waqf to allow redistribution.

Public Awareness and the Future

Why don’t more people know about this? Because there has been deliberate silence around waqf’s unchecked authority. Can the media and civil society challenge the system? Yes, but it requires legal activism, investigative journalism, and mass awareness. What happens next? If reforms don’t come soon, India will have a state within a state, a parallel land system immune to scrutiny. The question is: Will India follow the path of Turkey and Egypt in reforming waqf, or will it continue down the road of unchecked religious land monopolization?

The future of Indian land isn’t just about real estate. It’s about civilizational survival. The passage of the Waqf (Amendment) Bill in the Lok Sabha is not just a legal reform, it is a tectonic shift in how land, power, and history intersect in modern India. By allowing non-Muslims on Waqf Boards and mandating government oversight on land ownership, the bill signals an attempt to break the opaque walls of institutionalized land control. Supporters hail it as a long-overdue correction to unchecked monopolization, while critics see it as an intrusion into religious autonomy. The renaming of the Waqf Act to the Unified Waqf Management, Empowerment, Efficiency, and Development Act is not merely symbolic; it represents an assertion of state authority over what has, for centuries, functioned as an autonomous power structure.

But at its core, this debate is not just about waqf. It is about the fundamental question of land ownership in India. Who controls land, and in whose name? What happens when religious institutions wield enormous territorial power in a secular republic? How does a society reconcile historical landholding traditions with modern principles of equity and transparency? Mathura, Kashi, and thousands of other sites whisper the same question: is this a legal matter, a political struggle, or a deeper civilizational reckoning? As the bill moves to the Upper House, the fault lines in India’s land politics will only deepen. The discourse on waqf is no longer confined to Muslim institutions, it is now a national conversation on governance, identity, and historical justice. What happens next will define not just waqf, but the very nature of land, faith, and state power in India’s unfolding future.

- 162 min read

- 5

- 0