- Visitor:53

- Published on: 2024-07-01 12:19 pm

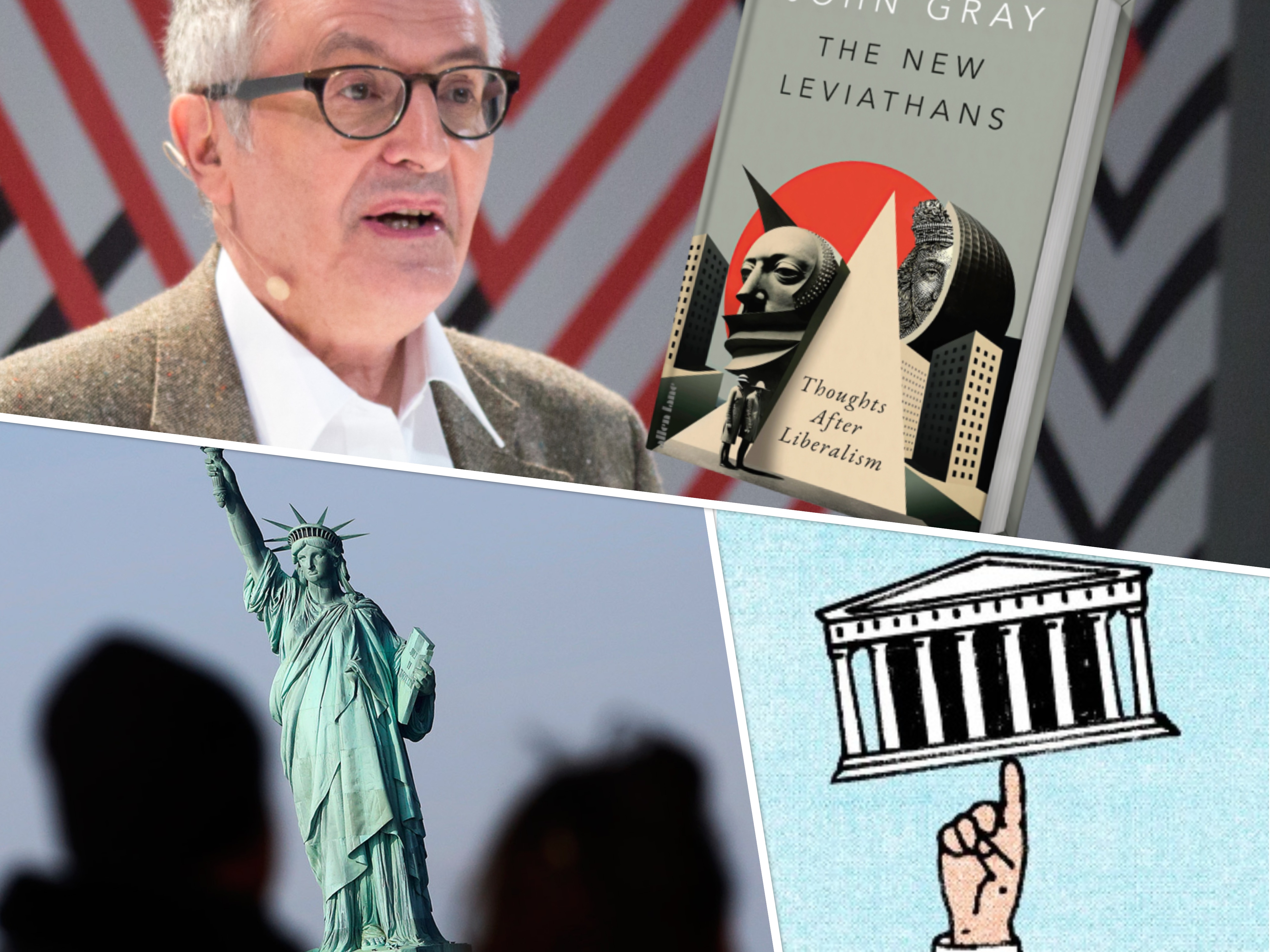

Is Liberal Legalism replacing Politics and Culture?

In the United States …every moral and political dispute is cast in the legalistic idiom of rights discourse. Accordingly, the courts, and for that matter the entire procedure of judicial review, have become theatres of doctrinal conflict … Litigation substitutes for political reasoning, and the matrix of conventions, subterfuges, and countervailing powers on which any civil society must stand are weakened or distorted … [by] the political self-assertion of collective identities, each of which seeks privileges and entitlements which cannot in their nature be extended to all … it is not hard to see the United States as heading for an Argentine-style nemesis, in which economic weakness, over-extended government and doctrinal excess compound with each other to lay waste the inheritance of civility.

Force, and

fraud, are in war the two cardinal virtues- Leviathan, Chapter 13

It seemed clear

to one observer, writing in 1989, that the American experiment in rights-based

liberalism was heading for a fall:

In the United States …every moral and political

dispute is cast in the legalistic idiom of rights discourse. Accordingly, the

courts, and for that matter the entire procedure of judicial review, have

become theatres of doctrinal conflict … Litigation substitutes for political

reasoning, and the matrix of conventions, subterfuges, and countervailing

powers on which any civil society must stand are weakened or distorted … [by]

the political self-assertion of collective identities, each of which seeks

privileges and entitlements which cannot in their nature be extended to all …

it is not hard to see the United States as heading for an Argentine-style

nemesis, in which economic weakness, over-extended government and doctrinal

excess compound with each other to lay waste the inheritance of civility.

The same

observer, writing in 1992, suggested that the nemesis might come via conflict

over abortion:

If the

theoretical goal of the new liberalism is the supplanting of politics by law,

its practical result – especially in the United States … – has been the

emptying of political life of substantive argument and the political corruption

of law. Issues, such as abortion, that in many other countries have been

resolved by a legislative settlement that involves compromises and which is

known to be politically renegotiable, are in the legalist culture of the United

States matters … that are intractably contested and which threaten to become

enemies of civil peace.

The new

liberalism to which I referred was articulated in the writings of the American

philosophers John Rawls and Ronald Dworkin. The details of their philosophies

have little interest. Rights-based liberalism is as remote from

twenty-first-century realities as medieval political theory, if not more so.

History has

passed by any idea that law can insulate liberal values from political

contestation. A bill of rights may be useful in codifying liberties and

entitlements, but it will be viable only insofar as it expresses values that

are widely shared in society. When there are deep and abiding ethical

divisions, rights are overturned by the political capture of the judiciary.

After decades of activism by ‘right-to-life’ groups, this has been the result

in America. The next stage, no less predictable, is a breakdown of law.

Liberal rights

are political projects promoted by the use of state power. Westward expansion

in the United States involved assaults on indigenous peoples that at times are

hard to distinguish from genocide. Market capitalism did not emerge

spontaneously, in a process of voluntary exchange, from feudalism. The free

market was a construction of the state, which enclosed common land and

expropriated smallholders. In being imposed from above on recalcitrant

populations, nineteenth-century capitalism had much in common with

twentieth-century communism. As Hobbes wrote in the Conclusion of Leviathan,

‘there is scarce a Commonwealth in the world, whose beginnings can in

conscience be justified.’

Liberal legalism aimed to replace politics by the

adjudication of rights. But, whereas politics can never be a branch of law, law

can become a branch of politics. Conflicts of rights reflect divergent

understandings of the human good, which cannot be resolved by legal

arbitration. Abortion is one such conflict. Attempting to de-politicize the

issue politicizes law and turns politics into a mode of warfare.

When Roe v Wade

– the 1973 Supreme Court decision ruling that the American Constitution protects

a woman’s freedom to have an abortion – was revoked in June 2022, around two

dozen states prohibited the practice, some of them in cases of rape and incest,

while exposing doctors and health workers who facilitate the procedure to

criminal charges. The Court is not prohibiting abortion. It is devolving the

issue to Congress and state legislatures. But conservative judges may go on to

challenge contraception and same-sex marriage as well. A moral

counter-revolution is being mounted by means of the political capture of the

American judicial system.

A school of

anti-liberal ‘integralism’24 welcomes this move. The foundations of the

American regime are in the Christian religion. The last church to have a

special relationship with the state, the Congregationalist Church in

Massachusetts, was disestablished in 1833. Yet Christian values continue to be

widely authoritative if not often practised. When these values are unmoored

from their theological matrix, they become inordinate and extreme. Society

descends into a state of moral warfare unrestrained by the Christian insight

into human imperfection.

Liberalism is

self-undermining in precisely this way, but the vision of an American

integralist regime is chimerical. Several European democracies have established

churches. In Denmark, Finland, Spain, Austria and Portugal there is a more or

less formal marriage between the state and a particular church. The British

state contains two established churches – the Anglican Church of England and

the Presbyterian Church in Scotland. All these countries are less divided by

issues originating in religious belief than the US.

In America at

the present time, an attempt at unifying church and state can only heighten

divisions. Any such project would be resisted at many levels of government.

Awash with guns and with large numbers ready to use them, the country could

slide into a chronic condition of low-intensity civil war. The US would be a semi-failed state possessing formidable military

capabilities and leading in some advanced technologies, but consumed by

internecine doctrinal enmities.

Whether the

Supreme Court’s judgment on Roe was legally correct is unimportant. Whatever it

decided could not end conflict over abortion. Framed as a contest between

rights to life and choice, the dispute is irresolvable. If one wins, the other

loses. In the US, neither side is ready to concede defeat.

Whether the

Constitution gives any guidance on abortion is questionable. Even if it does,

the Constitution’s authority is strictly local. Rawls and Dworkin aim to show

that American jurisprudence presupposes liberal rights. But of what interest is

such a deduction beyond American shores? Without some foundation beyond

American history and practice, liberal legalism is Lockeanism in one country – a

country that is profoundly divided.

Locke’s

philosophy of rights begins with a theological proposition: human beings are

God’s property. Contrary to a legend propagated by the libertarian Robert

Nozick, there is no right of self-ownership in Locke, who wrote in the Second

Treatise of Government, Section 6:

… for men being

all the Workmanship of one omnipotent and infinitely wise Maker; all the

servants of one Sovereign Master, sent in to the world by his order and about

his business, they are his property, whose workmanship they are, made to last

during his, not one another’s pleasure …

Locke’s belief

that human beings belong to God precludes any right to abortion or to suicide.

In his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (Book 1, Chapter 3, Section 19),

where he described abortion as one of the most immoral acts, Locke argued that

human beings have an immortal soul that belongs to its Creator. The lives of

human beings are not theirs to begin or end.

Against this

view, Hobbes asserted that women have dominion over their bodies and therefore

over their offspring. In De Cive, Chapter 9, he wrote:

… Amazons have

in former times waged war against their adversaries, and disposed of their

children of their own wills, and at this day in diverse places, women are invested

with the principal authority … the child is therefore his whose the mother will

have it, and therefore hers; wherefore original dominion over children belongs

to the Mother …

Hobbesian logic does not require accepting any particular view of abortion, even Hobbes’s. The goal is not agreement, but modus vivendi. A legal framework governing abortion can only be reached by a political settlement, periodically renegotiated. The same applies to issues around assisted dying, sexuality and gender. When society is divided on such questions, the attempt to resolve them by inventing and enforcing rights is fatal to peace.

Bibliography:

Gray,

J., 2023, Warring rights, The new Leviathans: thoughts after

liberalism, p. 103.

Center for Indic Studies is now on Telegram. For regular updates on Indic Varta, Indic Talks and Indic Courses at CIS, please subscribe to our telegram channel !

- 26 min read

- 1

- 0