- Visitor:27

- Published on:

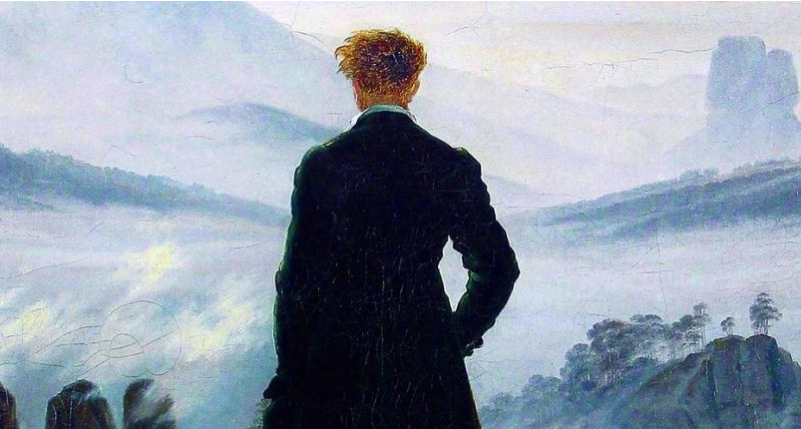

The Violence of the Romantic View of Life

In this concluding part of series on the effect of sentimental romanticism on human society, Theodore Dalrymple tells us that the romantic and sentimental view of the most important aspects of human existence are therefore intimately connected to the violence and brutality of daily life, which has almost certainly worsened in Britain over the last sixty years, notwithstanding the immense improvements in levels of physical comfort and well-being. This is an excerpt of the book ‘Spoilt Rotten – The Toxic Cult of Sentimentality’.

The romantic and sentimental view of the most important aspects of human existence are therefore intimately connected to the violence and brutality of daily life, which has almost certainly worsened in Britain over the last sixty years, notwithstanding the immense improvements in levels of physical comfort and well-being.

It remains to be pointed out that one of the consequences of the general adoption of the romantic and sentimental view of human existence is a blurring of boundaries between the permissible and the impermissible: for life itself decrees that not everything is or can be permissible. It is simply impossible to live as if it were true that it is better to strangle babies than let them, or anyone else, have unacted desires.

But the blurring of boundaries occasioned by the adoption of an impossible view as if it were true, and the consequent refusal of individuals to accept limitations on their own lives imposed by extraneous forces, that is to say forces that are independent of their will or whim, such as social convention, contract and the like, means that uncertainty becomes not the province of intellectual speculation, but of the very way that life should be lived. Uncertainty, by means of reaction against it, breeds intolerance and violence.

Nowhere is this seen more clearly than in the question of sexuality and childhood. Assuming that there must be a legal age of consent to sexual relations, the fact remains that any age that is chosen must, to an extent, be arbitrary. It is absurd to suppose that, if it is sixteen, a child of 15 years and 364 days actually and in reality has matured one day later to such an extent that he or she is capable of deciding what he or she was previously incapable of deciding. The same would be true of any age chosen.

From this it seems to be the case that what is legally impermissible may nonetheless be morally and practically permissible — at least, that is the conclusion that has been drawn by most people in our society. A fifteen year-old cannot legally consent to sexual relations, and all such relations are therefore criminal; but doctors are enjoined to prescribe even younger children with contraceptives without informing their parents, publications designed for eleven and twelve year-olds are often an explicit invitation to sexual behaviour, and there is no doubt whatever that many parents connive at the illegal sexual activities of their children.

It is true that some men are still convicted of having had sexual intercourse with girls who were under the age of consent, but they often claim, not wholly implausibly, that the girls in question did not look their age and were allowed by their parents out at a time when one would not expect girls of such an age to be allowed out (in the general drunken and drug-fuelled sexual sauve-qui-peut that takes place in the centre of British town and city every Friday and Saturday night it is hardly to be expected that inspection of birth certificates should be demanded and accorded).

Furthermore, the men claim that they are being punished not so much for having had sexual intercourse with such girls, but in effect for stopping having had sexual relations with such girls: the girls being unhappy at the cessation, they run to their parents — who already knew of the relations — and ask that they should go to the police. The convicted men feel aggrieved not because they are innocent of the charge, but because they have only done what many others have done and continue to do, with the knowledge and even approval of the parents of the girls. The age of consent thus becomes not a rule to be obeyed, but a weapon to be wielded.

More importantly, the social conditions in which sexual abuse of children is most likely to occur have been assiduously promoted first by intellectuals and then by the state. And those with a guilty conscience often seek a scapegoat by means of which to expiate themselves.

The current scapegoat in Britain for the neglect and abuse of children that is consequent upon the refusal of the population to place a limit on its own appetites (to quote Burke), is paedophilia. This is not to deny the seriousness of paedophilia: I am not sure whether the supply creates the demand or the demand the supply, but there can be little doubt of the horrors committed against children so that images of what is done to them may be sold over the internet.

In the nature of things, it is difficult to know whether the worst forms of paedophilia are on the increase or not; but the fact remains that a child is vastly more likely to be abused at home, by a member of the household or at least a frequent visitor to the household, than by anyone else. And millions of people have contributed to the maximization of the chances.

And so it is to paedophiles and paedophilia that the guilty hysteria of the population is directed. So great has it become that on one infamous occasion a paediatrician’s house was stoned by a mob, paediatrics and paedophilia being indistinguishable to them. In Britain, scenes outside courts of mob hostility towards alleged paedophiles who are being brought to appear there (the notion that a man is innocent until proven guilty being completely alien to the mob) have become quite common; and women, often with a terrified child in tow, scream abuse and even hurl missiles at the vehicles containing the alleged malefactor, apparently unaware that to expose a child to such scenes is abusive. It is a racing certainty that most of the women who behave in this way live in the very circumstances that are most likely to give rise to the sexual abuse of children. Were it not for the presence of the police, it is likely that in such scenes torture followed by a lynching might very well take place.

The connection between sentimentality and lynch law is further demonstrated by the violence of prisoners towards their co-detainees who are guilty of (or merely on remand for) sexual offences. The rationale for this violence is that the sex offenders ‘interfere with little kiddies’ — always little kiddies, by the way, and never mere children. The authorities have to protect the offenders from the sentimental wrath of men who, not infrequently, have themselves caused a great deal of misery to others and acted brutally, and who are great getters and neglecters of children.

Sentimentality is the progenitor, the godparent, the midwife of brutality.

- 13 min read

- 0

- 0