- Visitor:154

- Published on: 2025-07-23 03:56 pm

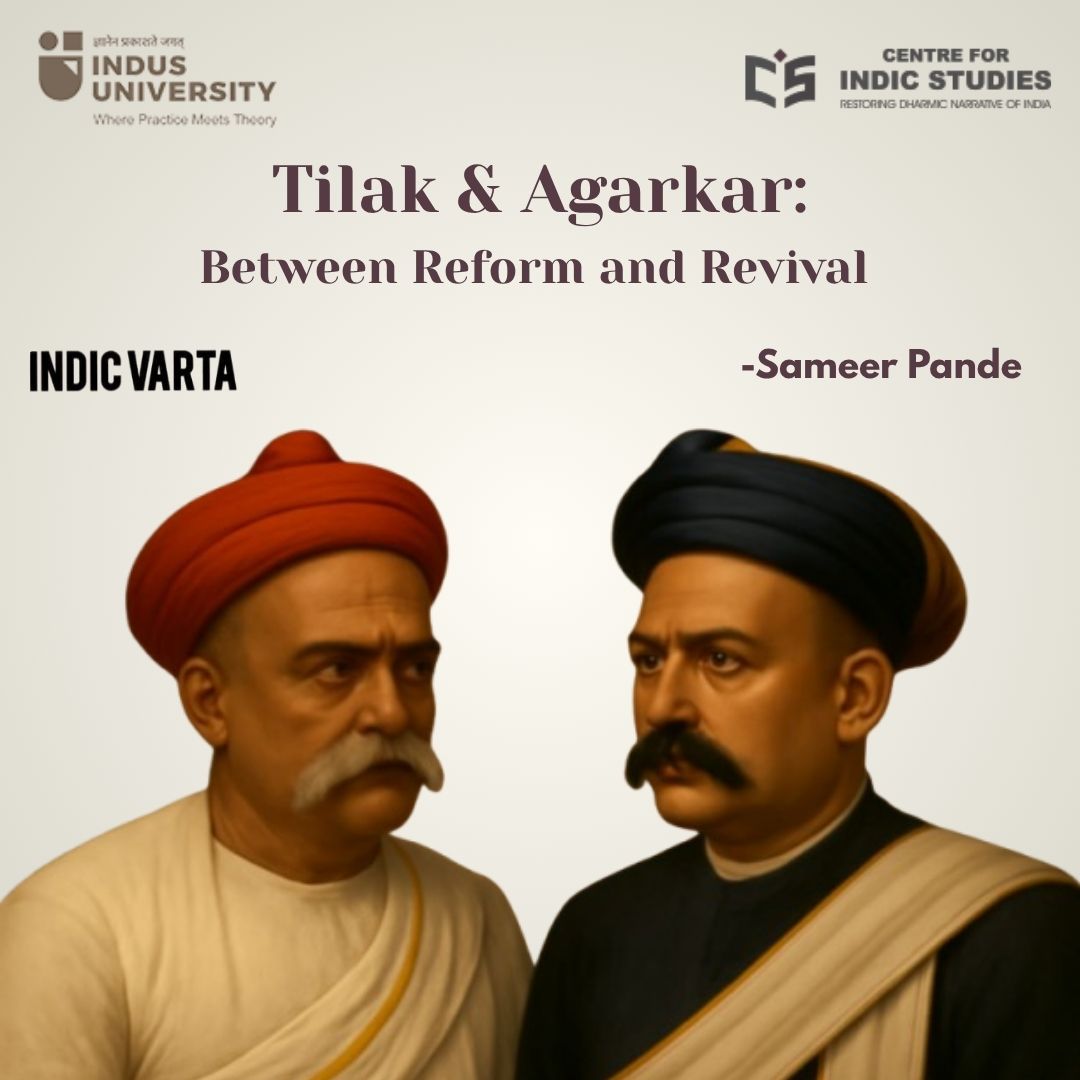

Tilak and Agarkar: Between Reform and Revival

“Should the lamp of reform be lit from within, or must it be handed down by foreign hands?” The question is not merely a historical question; it is a civilizational conundrum. And nowhere is it more vividly dramatized than in the charged debates between two towering figures of 19th-century Maharashtra: Gopal Ganesh Agarkar and Bal Gangadhar Tilak. What begins as a dispute between colleagues, friends, over salary and editorial tone, unfolds into a profound philosophical divergence on the nature, purpose, and agency of reform in India.

To understand the Tilak–Agarkar debate is to confront an old yet evergreen dilemma: Is reform a rupture, or is it a rejuvenation?

Let’s first understand their historical background.

Gopal Ganesh Agarkar was born on July 14, 1856, in the village of Tembhu in the Satara district of Maharashtra. Coming from a modest Chitpavan Brahmin family, Agarkar’s early brilliance found its home in the world of books. He graduated with a Master’s degree in Philosophy from Deccan College in 1880, a time when ideas of liberty, equality, and rationalism from the West were sweeping across the educated Indian mind. Agarkar was not merely influenced by these ideas; he embodied them. For him, reason was not a luxury but a necessity. Alongside Tilak and others, he co-founded the Deccan Education Society and Fergusson College, both envisioned as bastions of Indian-led education that would prepare a new generation to think, question, and rebuild. But while his early steps ran parallel to Tilak’s, his destination was different. Agarkar became the first editor of Kesari, giving voice to nationalist thought. Yet soon, he turned toward a different mission, social reform. Breaking away from Kesari, he launched Sudharak in 1888, a journal that fearlessly critiqued caste orthodoxy, gender injustice, and religious dogma. Widow remarriage, women’s education, and caste equality were not just issues for him, they were moral imperatives. Agarkar believed that unless society was just, political freedom would be hollow. His life, though brief, he died in 1895 at the age of 39, was a burning lamp of ethical reform, carried forward by rational conviction, even at the cost of popular opposition.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak, born just days later on July 23, 1856, in Ratnagiri, belonged to the same Chitpavan Brahmin milieu but followed a different inner calling. Trained in Mathematics and Law, he too graduated from Deccan College and became a teacher before turning to journalism and politics. Tilak, like Agarkar, co-founded the Deccan Education Society and Fergusson College, but where Agarkar saw education as a means to moral rationality, Tilak saw it as a path to national resurgence. As editor of Kesari after Agarkar, Tilak transformed the paper into a platform for civilizational pride, cultural awakening, and political resistance. He wasn’t content with reforming Indian society under the gaze of British liberalism, he wanted to awaken its sleeping soul. With tools like the public Ganesh festival and the Shivaji Utsav, Tilak infused religious-cultural life with nationalist meaning. To him, British rule was not merely a political problem but a civilizational humiliation, a breaking of national self-respect. Tilak’s famous assertion, “Swaraj is my birthright and I shall have it”, echoed not just political defiance but also a metaphysical claim to selfhood. He was imprisoned multiple times for sedition, including a six-year term in Mandalay, yet returned each time with greater resolve. His nationalism was not borrowed from the West, it was born from Dharma, from the lived memory of a civilization that must heal before it can rise.

Both men shared a birth year, a classroom, a mission, and even a newspaper. Yet they choose different paths. Agarkar wanted to reform society to make it worthy of freedom. Tilak believed freedom was the condition in which true reform could occur. One drew from European Enlightenment, the other from Indic civilizational memory. In their divergence lies not contradiction, but the deeper dialectic of India’s modern mind, between purification and preservation, between critique and continuity. Together, they did not merely argue; they shaped the future debates of Indian thought.

A Common Dream

There was a time when the idea of Maharashtra was not just political, it was pedagogical. Not the Maharashtra of power corridors and factional alliances, but the Maharashtra of minds on fire (Maharashtra was not yet formed politically). Before political parties were born, there was a shared pursuit of awakening. And in that sacred intellectual dawn stood two titans: Tilak and Agarkar. Not as rivals. As companions. Co-dreamers. Co-founders. Co-conspirators in the war against ignorance.

Together, they built more than institutions, they built imaginations. The New English School wasn’t just a building; it was a break from colonial mental chains. The Deccan Education Society wasn’t just an organization; it was a declaration of svatantrya in thought. Fergusson College wasn’t just a campus; it was a civilizational institution, where young minds would battle alien paradigms and rediscover the true idea of Bharat.

Agarkar was the pen. Tilak was the fire. As Kesari's first editor, Agarkar carved modernity onto Marathi consciousness, rational, reformist, Enlightenment-infused. He believed that the shackles weren’t just British, but also within. Superstition, orthodoxy, caste, he saw them as the deeper chains. To him, emancipation meant questioning everything, even tradition.

Tilak, however, heard a different drumbeat. Not one of rupture, but of resurgence. The Bhagavad Gita, not Bentham. The Puranas, not Paris. For Tilak, our past was not a prison, but a treasure map. His nationalism was not secular liberalism in Indian garb, it was rooted in the soul of this land woven into the idea of self-rule. And so, like the Godavari and Krishna flowing from the same Sahyadri ranges but finding different paths, they parted.

Agarkar turned westward, in search of reform through critique.

Tilak turned inward, in search of strength through continuity.

But Maharashtra remembered both. As a contradiction, yes, but also as a complement. Because what was Maharashtra facing was the dilemma between the fire of justice and the fire of pride. From this early divergence flowed the many political thoughts that would later course through Maharashtra. The Prabodhankars and Phules, Ambedkars and Savarkars, each carrying traces of Tilak’s assertiveness or Agarkar’s critique, or both. The Samajwadis who wanted equality. The Hindutvavadis who sought identity. The Congressmen who once channeled both reason and religion, only to forget them both in time.

And today, as we watch Maharashtra’s politics turn from ideology to identity, from vision to vendetta, one wonders: Do we still remember the common dream? That dream where education wasn’t just a degree, but an awakening to ancient knowledge? Where politics wasn’t about chairs, but about rashtra chitta?

Tilak and Agarkar remind us: Civilizations don’t collapse when enemies attack. They collapse when friends forget. So let us not forget. Let us remember that before divergence, there was unity. Before debate, there was trust. Before ideology, there was shraddha, not in dogma, but in each other.

Let that be the Maharashtra we revive.

The Great Schism: Reform or Revolt?

What broke between Tilak and Agarkar wasn’t just friendship, it was a fracture in the very drishti through which they viewed Bharat. The surface spark may have been about Kesari’s editorial tone, or Tilak's salary dispensation. But deep below that quarrel lay a tectonic epistemic rift: What is India’s illness and what is the cure?

Agarkar, sharp as a scalpel, saw society as a corrupt edifice, held up by caste, superstition, and patriarchy. To him, the task was not healing but dismantling. For him, opposite to Tilak, British law and Enlightenment reasons weren’t colonizers, they were tools of justice, instruments to carve out a new moral order. Sudharak, his journal, did not whisper reform; it thundered against ritualism, misogyny, and social inertia.

Tilak, rooted like an old Banyan, saw things differently. Society wasn’t a machine gone wrong, it was a sacred body, scarred but not sick beyond redemption. And its soul was Dharma, not law books from London or cold calculus from France. He didn’t reject reform, but demanded it speak in the tongue of the Gita, not in the grammar of guilt. Kesari became his shankh, blowing not for shame, but for resurgence.

Agarkar declared: “First cleanse society, then ask for freedom.”

Tilak roared: “First win freedom, then reclaim your society.”

And so the schism was born. Not just between two men, but between two Indias. One wanting a revolution of ethics, the other a revolution of spirit. This divide still haunts us. When we debate laws, customs, rights, and roots, Agarkar and Tilak still sit silently in the room. Watching

Tilak’s greatest fear was not foreign rule, it was the shattering of civilizational self-esteem. He saw a nation gaslit into shame, nudged to see its roots as rot. Social reform, when orchestrated by colonial hands or mimicked uncritically, was to him not liberation but slow suicide. It fragmented what needed integration. It insulted what needed introspection.

Agarkar countered with the sharp edge of moral clarity. What Swaraj, he asked, if half the nation lives in chains at home? He cited Tarabai Shinde not as ornamentation, but as indictment. Casteism, gender oppression, irrationality, these were not ‘fringe issues’ to be postponed. They were the issue. Their paradigms were irreconcilable:

Agarkar: Society is sick; Reason is the cure.

Tilak: Society is sacred; Dharma is the pulse.

Agarkar diagnosed, dissected, demanded. But his medicines were borrowed from Europe’s Enlightenment which carried side effects: alienation, mimicry, rootlessness. Tilak, slow and sometimes obstinate, preferred the painstaking path of internal realignment. He mistrusted borrowed scalpels on civilizational wounds. Both were right. And both were wrong. The tragedy was not in their divergence, It was in our failure to synthesize their visions.

Reform in the Indic Ethos

Reform is not a Western invention, it is woven into the Indian fabric. The Upanishads re-scripted the Vedas. Bhakti saints dissolved walls thicker than stone. Nanak scorned the hollow ritual. Mirabai danced over orthodoxy with divine abandon. Indic reform is not a revolution of rupture, it is constant inner tuning, like a tanpura that adjusts itself mid-raga.

Where the West shouts, “Break the past to build the future,”

Bharat whispers, “Refine the past to rediscover the eternal.”

This is the core difference: Western reform: Replace. Indic reform: Realign. To call Dharma stagnant is to misread its rhythm. It is not static, it breathes through correction, through yugadharma, not guilt.

Colonial Modernity: A Mirage?

Agarkar, like many brilliant minds of his time, saw modernity through a one-way mirror, clear in one direction, but distorting the other. British law, education, and moral posturing appeared rational, fair, universal. But beneath the veneer lay design: Divide and catalogue. Codify caste. Reify religion. Turn Dharma into “Hinduism.” Turn diversity into data. In seeking to heal society, Agarkar sometimes trusted the surgeon who created the wound. But, his critique was right, at par.

Tilak, with all his flaws, sniffed the danger. He knew that civilization cannot be rescued by those who wish to rewrite it. His resistance was not to reform, but to reform that forgets where it stands. Agarkar’s intentions were luminous, but his tools were foreign. Tilak’s instincts were indigenous, but his methods were slow.

One critiqued from the head. The other defended from the soul. And India still walks that faultline

Beyond Binary: Dharma Over Dogma

The Tilak–Agarkar debate is not merely a standoff between "Right" and "Left", or tradition and modernity. These are imported binaries. Their dialogue was rooted deeper, in the churn between rakshan (preservation) and shodhan (purification). It was not a power struggle, but a philosophical tug-of-war between continuity and conscience.

They were not enemies. As Yashodabai, Agarkar’s wife, later wrote with poignant honesty, there was no bitterness in their final meeting. The schism was intellectual, not personal.

Their debate echoes civilizational contests, it was grounded in samskriti, not just in social theory. Only in a living civilization like Bharat can reform take the form of an inner dialogue rather than a cultural divorce. Where the West breaks to build anew, Bharat argues, adapts, and realigns.

Reforms: Who Demands, Who Remembers?

A question haunts our reformist history: Who demanded change? And who do we choose to remember? Many 19th-century reformers came from so-called “elite” backgrounds, Tilak, Agarkar, Ranade, Gokhale. But does that negate their intent? Were they tools of colonialism, or torchbearers of Dharma’s internal ethics?

Social reform in India wasn’t the monopoly of any one caste or community. Ramabai spoke from within womanhood. Tarabai Shinde from the intersections of gender and caste. Even tribal voices and regional saints echoed the call for justice long before English-educated voices took the stage.

But memory is political. We canonize some and forget the rest. We read about Raja Ram Mohan Roy but not Kashibai Kanitkar. We quote Tilak, but rarely explore the fierce moral vision of Agarkar. We simplify for convenience, and in doing so, erase nuance.

And layered over all this is the colonial lens, classifying reformers as “conservative” or “progressive” through Victorian categories, not Indic ones.

Conclusion: Awakening, Not Aping

The questions that haunted Tilak and Agarkar are far from settled. Caste, gender, justice, education, they persist. But as we navigate them today, we must ask:

Are our reforms rooted in Bodh (inner awakening), or are they reactions scripted by global templates? To reform from guilt is to imitate. To reform from Dharma is to remember.

Tilak reminded us that shame is not a foundation for national rebirth. Agarkar urged us that uncritical pride is no cure either.

Their difference is our inheritance and our challenge.

Reform must not become rebellion against the self. It must be Shodhana, a sacred alignment.

Not erasure, but evolution.

Not mimicry, but maturation.

In the end, it is Dharma, not dogma, that lights the way. And only when reform flows from within does it cease to be a scar and become a samskāra.

- 77 min read

- 7

- 0